A Nighttime Walk with Garnette Cadogan

"Truth be told, if walking was bad for me I’d still be doing it."

“Tuesday. 8:30pm. I’m taking you to dinner. After dinner we will walk ‘til the break of dawn. What say you?”

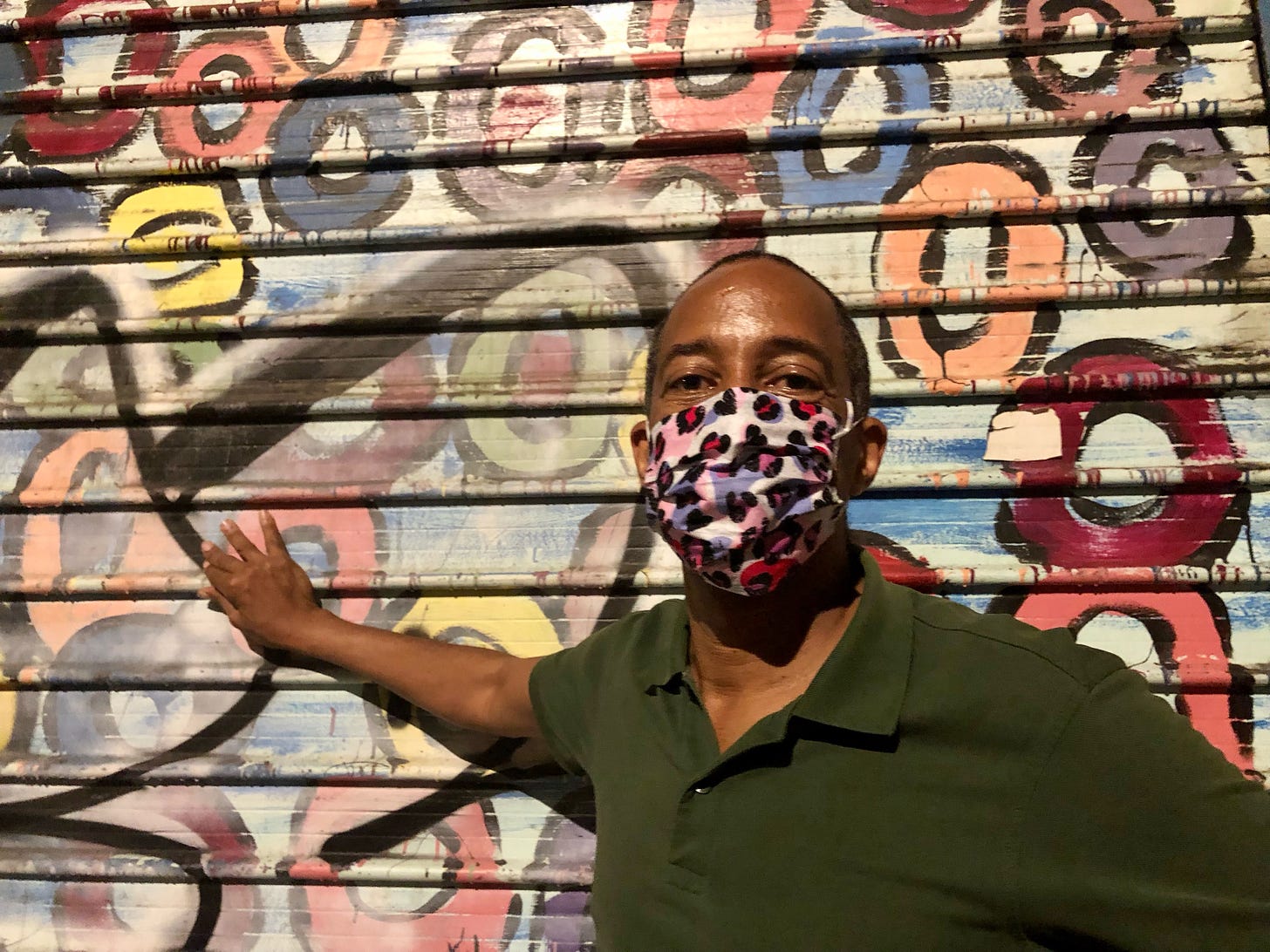

The text is from Garnette Cadogan and I am thrilled. I have been wanting to walk with Garnette—whose essay, “Walking While Black,” is a must-read—since I first dreamed up the concept for Walk It Off. He was one of my first asks, and now he’s finally in New York.

“Let’s do it!” I text in response. “Where should I meet you?”

The answer is the southwest corner of East 6th Street and 1st Avenue in Manhattan, which is where I am that Tuesday evening when Garnette embraces me.

“Isaac! It’s been too long.”

We are standing in front of a fancy restaurant and the dinner Garnette proposed is actually a fabulous outdoor dinner party, for which I am his plus one. There are name cards and seating arrangements and incredible guests. There’s always a surprise when Garnette is in town. I watch as he moves from table to table, putting people at ease, making them laugh, or sitting down to listen to a story they want to tell. The night quickly slips aways from us and by the time we leave, midnight has come and gone.

Garnette isn’t worried, though. There’s still plenty of time before sunrise. He sets out, his stride relaxed but purposeful. It’s hard to describe, but it doesn’t seem as if Garnette has started walking so much as he is simply continuing a walk that he’s been on all day—or maybe his entire life. Either way, I do a half-run to catch up with him, feeling the wine that I drank slosh in my stomach. I fumble my notebook out of my pocket and search for my first question, but before I can find the page, Garnette begins to speak.

Garnette Cadogan: So much of New York is forward-looking. “Ahead. Ahead. Ahead.” Sometimes it feels like the entire city is living within a scaffolding. Always building to get somewhere else rather than properly inhabiting the space that one is in. And that means too often a reluctance to look back.

It’s a contrary impulse that motivates my frequent walks on Bowery. People used to come here to get equipment for their restaurants. And they still do. Sno-cone machines. Meat slicers. Espresso machines. Pasta makers. Egg beaters. This whole district is filled with rooms containing pots and pans and knives. Many people who visit these blocks work in the service industry; they have a livelihood in restaurants or catering services. And it’s been like that for decades. Two decades ago you’d see the equipment line these sidewalks we are sauntering on.

Walking here, from East Houston down to Prince Street, you’re reminded of the past. You’re reminded of an old New York. An older New York that still exists even if it no longer flourishes. Here is a New York that looks ahead with a hand on its past. I love places in the city where you can see New York City as a place of possibility—the New York City of the future—without losing sight of the New York City from times past.

There’s a beauty in searching through the city to find these layers. Peeling them off to see one layer beneath the other, one story beneath the other. Searching for historical New York. Here, on Bowery—and in many other places in New York—the past feels present. And I love that. I love walking where the past jumps out at you from the windows, or at least waves.

Isaac: What drew you to New York when you first came here?

GC: I first visited New York in 2001. There was a conference at the Center for Jazz Studies at Columbia University. And I am a lover of jazz, ready to chase it wherever it can be heard—the conference had a terrific accompanying concert; all conferences should be like this. I can hear my Spotify playlist saying, “He’s lying. He’s into 80s music.” But I also love jazz. So I came up from New Orleans, another great jazz city and where I was living at the time. I fell in love with this city immediately. For all the reasons people fall in love with New York City—the vibrancy, the variety, the fascinating cultures, the multifaceted peoples and beliefs.

Chief among my loves is the city’s many overlapping and adjoining rhythms. The rhythm of St. George in Staten Island is very different from that of upper Manhattan, which is quite different from eastern Queens, which is different from Midtown, which is different from the Lower East Side, which is different from Kingsbridge in the Bronx, where I lived for most of a decade when I eventually moved to New York City. An obvious point, but neighborhoods wildly and wonderfully different from each other makes the city beguiling to me. A glorious difference that prompts many different ways of being. Many different ways of existing and coexisting in this city with its energizing possibilities and severe inequalities and deep ironies. Yup, New York captivated me from the very beginning.

But it was especially as a night owl that I fell in love with New York City. From my first dusk, I understood what a great city this was for night walks.

I: What do you love about walking at night?

GC: Night walks are incredibly important. The city becomes a different creature at night. There are levels of intimacy, of openness, of freedom, of control, of interaction, of encounter, that far surpasses—or, at least, offers a very different quality than—those of the day. People get drawn into associations and affinities that come from seeing each other regularly at night. In part, because places are more sparse; less obstructions to a welcoming eye contact. You feel it on the sidewalks, in the streets, and in the alleyways. The stoops are yours much more so than during the day. The very atmosphere feels more ready to accommodate you. Many places have one, singular, ingrained core story during the daytime, but at night? At night, these places give up many stories. A multiplicity of stories waiting to reveal themselves to you.

I: Do you have a preference between, let’s call them Day New York and Night New York?

GC: Give me Night New York over Day New York a million times over. That may partly be due to my constitution, and less to do with New York. I come alive at night. My friends say I get my second wind at midnight, but the truth is I get my first wind at midnight. My second wind hits at around three o’clock. I love the night. I love the sense of mystery that comes with it.

I: Was that true when you were younger? When you were growing up?

GC: It was and it wasn’t. The night was something that I sort of stumbled into. I would be at friends’ homes—relaxing at one friend’s place or another—because my home was a place I found undesirable. It was an abusive home because of my stepfather. He felt that I was good for boxing practice, and I got tired of being a body bag. Clearly, I wanted to be everywhere but there. Home wasn’t a home.

So I started coming home late at night, after public transportation ended its daily run. Walking the streets at night, worried about its threats. I did my best to figure out the safest ways to get home, and that’s when the night said, “Hey, guess what? I have surprises and delights for you. There’s a concert here. There’s a street party over there. There are street vendors walking home who will pour buckets of wisdom on you about what life is truly like. They’ll teach you how to navigate the city. How to be streetwise. Why this fashion looks better than that fashion. Why this neighborhood is more fun than the others.” Suddenly the night opened up to me. The night, that keeper of secrets, slowly began to whisper its secrets. The night became the hermeneutic of the city. Night was when—was where; after all, it was now a place—I could find people who would explain to me life as it really was. The city as it is. The cycles and habits of the city were now laid bare.

I: Was this in Jamaica?

GC: Yes, this was in Jamaica, but it remains true wherever I go. At some point in my youth a thought soldered itself onto my legs, “Why not always explore the city at night? The night is not only a terrific zone—It’s the teacher who will help you navigate the day.” The night is when you see a city at its best, and also at its worst. The night feels more honest. And the city at night feels more revealing. It invites your scrutiny as you move at a slower, more observant, pace. During the day you’re probably rushing—sometimes at an inhuman speed—to get from one place to another, to do this and that along with hordes of other people. But at night you move through the city at a more human, and humane, pace. There’s a relationship to time, but also a relationship to other bodies, that makes you more aware—more attentive, more sensitive—to the people around you.

For example, now we’re in Chinatown. There are so many different Chinatowns at night. At day, too, but your relationship to space—think of the crowds—and time—consider how you rush—makes these Chinatowns more hidden. At night the city raises questions about what we miss. We raise those questions with the help of people who loiter—I prefer to say people who linger—at different places or street corners. These public interpreters of these places are effectively night mayors.

Even in a neighborhood you’re familiar with, once you begin speaking with the people who frequent it at night, you will be surprised at how much will be new to you. You get a fresh feel for that area. The more people you talk to, the more you see the neighborhood through their eyes, the more various mazes come together to form a lovely, interpretive grid. You grow in your understanding of the place and its people.

But I also love the lone figures of the night. The ones you won’t approach. You can tell they’re walking to get away from something. Maybe it’s their own thoughts. They are on their own, searching. It can be for mere peace and quiet, or clarity. Or they are trying to get away from frustrations or melancholy that takes up too much space in their lives. Maybe they’ve just lost someone. Or maybe they’ve just found someone and they’re trying to figure out how to express their joy for them.

You see people walking to escape, but also to travel toward a desired destination. They’re bopping to a soundtrack, lifting their spirits on the way to a get-together or party. Or they’re trying to figure out a problem, or searching for the right words to say to a loved one.

I: They’re processing something.

GC: Yes. I love these lone figures in the night who are, to paraphrase Kierkegaard, “Walking themselves into their better thoughts.”

I: At the risk of following up a Kierkegaard quote with a much simpler idea, walking at night during the summer is also cooler. Temperature wise. It’s more enjoyable, especially when we’ve been having such hot days. The sun goes down and the night is yours.

GC: That’s true, but I also like walking during extremely hot nights. When you can be sweaty and stinky and nasty, and judgements about that are less severe. I have a tribe of stinky people—of stinky thinkers—who love walking around at night, like me. Then there are people who have been working thirteen hours a day and they really stink—and they have every right to stink. We should celebrate them in their funkiness, because their smell is a result of hard labor. They have attended to—have taken care of, and made life better for—so many people. They’ve lifted this city up on their shoulders. We should celebrate their stink when we see them coming home from a late shift. So I celebrate the undesirable smells of the night. And I’m ready to take a hot night over a hot day.

Now, let’s not romanticize the night—there’s also an uncomfortable tension between you and others. People are apprehensive of you and wonder if they can trust you. There’s a wariness—the color of one’s skin, at times, can be the cause—or, sadly, it might be the thinness of one's wallet. The night is littered with awful examples of how unfree movements can be because of race and class. And, of course, gender. Sometimes when I’m walking at night and a woman sees me, she’ll cross the street because she assumes I’m dangerous—and rightly so; there’s thousands of years of history that should make a woman understandably wary of an unknown—or even known—male presence at night. So, at night, my very presence can be read as a vector of danger. My body is something dangerous. This is an experience many more people got a taste of since the pandemic, with people wondering if the body coming towards them was a carrier of Covid.

I: Distrust?

GC: Distrust, yes. That another body in your vicinity is something to be worried about. A body walking toward you is a threat approaching. We need to remember this as we celebrate walking at night—there are real fears that rise to meet real dangers that demand serious caution.

There is—no pun intended—a dark side to the city at night. Levels of vulnerability and issues of safety that are unlike anything you face during the day. But I also find an openness and a richness in the quality of interactions at night. Maybe at times even because of the tensions we are talking about. Once someone realizes the encounter is safe—“Oh, this person is not a threat”—and moves from worry to relief there’s a liberating sigh. And then a beauty that follows that sigh. “Hey, what’s up?” “Not much. What’s going on with you?” Maybe you start talking, or nod with increased friendliness. I love the beauty that follows relief. It can create a willingness to open up. I often meet someone new—or start a conversation, or share a laugh with a stranger—when my body is filled with that relief. The camaraderie that you experience is so wonderful.

[Editor’s note: We come across a group of young people on motorcycles, dirtbikes, four wheelers, and scooters at the corner of Mott Street at Chatham Square. I hold my phone up, asking permission to take a few pictures and they nod. The whole group talks and laughs as they rev their engines, and don’t seem to mind that Garnette and I stop to watch them.]

GC: One of the deep loves about the night is its dalliance with legality. There are ways of being in public space that you don’t see during the day because people are worried about getting arrested—or worse—or they’re worried about social disapproval. During the day, the streets are clogged with traffic and eyes whose disapproval troubles you more. At night the streets are empty, and you can take them over for your own purposes. Declare that it’s nobody’s business.

I: Having fun. Laughing. Enjoying life.

GC: I believe—more and more and more—we’re losing a sense of play. Especially in public space. Play is incredibly important to our fullness. And I worry that it’s in danger of being lost. Play creates togetherness, even tenderness. Play allows us to be in the world with an ease and a lightness and a lack of apprehensiveness. I’m ready to argue that when we play we’re closest to being our best, most human selves. The night encourages a playfulness and ease that is perhaps unmatched. I love seeing it. And sometimes that play runs alongside—or is skirting along, or actually is—breaking the rules. Here are a bunch of motorbikes on the sidewalk and I can’t, for the life of me, imagine that this is legal.

[Editor’s note: A signal ripples out through the group of bikers. It is a sign that both Garnette and I fail to catch, but all at once the bikes rev off into the dark streets in a cloud of wheelies and smoke.]

GC: Now you know why I love the night.

I: That was a bit miraculous.

GC: A perfect example of, “What might I see if I begin to give myself over to the city at night.”

I: What do you love about walking in general?

GC: The freedom. The ability to move and go in directions according to your senses. You see something you like, you hear something you like, you smell something you like. Simply following your interests, whether it’s music or color or shapes or patterns or communities or conversation. Moving according to your body’s own unpredictable and ever-changing tastes. Satisfying the need for something new. Honoring the desire to discover.

Even more than freedom, I value serendipity. I love the relationship between walking and surprise. Here we are, walking at 2am through Chinatown, talking about the ways people come together after the sun goes down, and suddenly we see a bunch of bikers revving their engines and getting ready for a night of jolly adventure. Watching a bunch of 12 O’clock Boys—which means wheeling on their bike exactly vertical, like the minute-and hour hands on 12 o’clock—and it is a marvel of human skill but also of human playfulness. What a beautiful moment. You and I are giddy because the freedom we find in walking got amplified by serendipity.

Walking is a chance to move at human pace. To move through a place and take it in at the speed at which we were meant to take things in. Absorb its smells and sounds and sights. To feel that place, even in the back of your throat, as you walk past the bakery and can almost taste that bread that lives in the wafts of the surrounding air. If I was driving here—on the Brooklyn Bridge—I couldn’t stop to take in the skyline. Or the smell of the air. I can’t stop someone and ask about the sneakers on his adventurous feet, or where she got her wonderful t-shirt that says, “Procrastinators of the world unite. Tomorrow.”

If you pass something—or miss something—walking allows a do-over. Kinda like writing, isn’t it? Allows you to circle back and say, “Hey, I saw this,” or, “I smelled this,” or “I heard this.” It allows for those things the way driving, or even cycling, doesn’t. There are untold joys you feel—that you truly feel—when you move through the world at a human pace. Walking affords a rich experience of the world around you unlike anything else.

But walking is also a chance to inscribe yourself onto a place. To leave bits of your personality—not merely your footsteps, not merely the signature of your steps. Because I think of walking as much more than “one step in front of the other,” I think of people moving in wheelchairs as walkers. What I fundamentally mean when I say “walking” is “moving at human pace.” Moving through the world and absorbing the world in its rich detail. At human pace. At human scale. And inscribing your personality, your character, your sensibility, your thoughts, your conversations, your stories onto the place you are moving through. I love how walking inscribes stories onto your consciousness and invites you to extend your own consciousness onto places. As you leave your signature, you learn how to recognize other signatures that have been left. You learn how to listen. To love. You participate in the past and the future by the mere movement of your body.

Walking changes a space into a place. It changes the unfamiliar to the familiar. It turns a stranger into a passerby and possibly into a neighbor. A friendly face becomes an invitation. Exchanges of hospitality can turn into a conversation. Maybe even a friendship—I have some very close friends who I met as strangers on a sidewalk. Walking changes my outdoors, and a quick jaunt will often lead to a brief but meaningful interaction.

Now, people will tell you that walking is good for your physical health. And your mental health. And your spiritual health. But none of that, praiseworthy as they are, gets me out my door onto the streets. I’m not a fan of the “eat your vegetables” approach to walking. There are many ways to be healthy. I’m not interested in walking to stay healthy. I’m interested in walking to encounter others. To learn about the world. To learn about myself in the world. To understand what it is to be in the world in all its richness and complexity and beauty and suffering. And to open my arms and embrace it.

Truth be told, if walking was bad for me I’d still be doing it.

It is 3:30am. We have walked through the Bowery and Chinatown and across the Brooklyn Bridge. In Brooklyn we have meandered through Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, and Prospect Heights. We spent some time looking for a bar, but all of them are closed. Another sign of the unsure times we are living in.

I am exhausted, but I have one last good thought in me. I point us towards Flatbush Avenue, and there we find Sharlene’s. The bar is still open. Last call. We buy beers and gulp down glasses of water. Garnette immediately befriends the few people still at the bar and a woman shows us her nails.

When the bar finally closes I turn to Garnette and make my confession. We’re only a few blocks away from my apartment. I need to go home. I will not make our destination. The sunrise.

There is no judgement on Garnette’s part. He just asks to walk me home.

“One of the last things I will say about walking is how it is truly and deeply a wonderful way to form a friendship. Two people walking alongside each other. Moving together in rhythm. Moving together at a human pace. Often the whole world will be closed off from them while they focus on their conversation. Or sometimes they let the world in, and observe it quietly together. Walking is a beautiful way to form a friendship.”

When we get to my apartment Garnette ends our evening in the same way we started it. He hugs me. And then, once he is sure I am safely inside, he walks into the night.

That was a fabulous read. I'm in awe of those who see hope and joy in spite of the drumbeat of madness destroying our world.

Garnette described walking at night in New York PERFECTLY!! No one has ever encapsulated what it feels like to walk those streets, experiencing the people, the vibes, the danger, the openness like he has. Especially for those of us who are night owls. Just perfect!!! Thank you for this!!