A Walk in the Wilderness of Forest Park with Stephanie Foo

"Protecting trees isn't altruism. It's a form of self-care."

“Can I follow you on Instagram?”

Stephanie Foo and I are walking in Forest Park in Queens, New York, and have stumbled across a bird photographer. Well, not so much stumbled across as alarmed, given that I all but shouted, “Holy shit!” when I saw the sheer number of birds—mostly bright red cardinals—in front of us.

The photographer is kind, though, and—in a hushed tone—tells us all about how she’s been photographing birds in Queens for years, but it wasn’t until the pandemic that she really began taking her photography seriously. She rattles off a litany of bird types which she shoots both here in the park and throughout Queens, but all I can remember now are cardinals and red-tailed hawks.

[Editor’s note: The photographer’s Instagram handle now resides in a notebook that I have since lost, which I regret, as I would have loved to link to her page.]

After sharing her Instagram, the photographer moves further into the thicket to get a better shot of a specific woodpecker. Stephanie Foo and I stand, surrounded by birds, and don’t say a word. We have already been walking for some time.

But let’s start at the beginning.

Isaac: Can you tell us where we are?

Stephanie Foo: We are in one of the truly wild places within New York City—Forest Park, which is in Queens. We’re on the blue trail and it’s lightly snowing, a magical time to be out here. Everything is lightly dusted in white and the park is deserted. Silent.

Forest Park is technically bigger than Prospect Park. Only by ten or so acres, but it is bigger. The park used to be even bigger, even more wild. But then, what’s his face, from The Power Broker—

I: Robert—

SF: Robert Moses. That’s right. But then Robert Moses plowed the Jackie Robinson Parkway through it. Still, I think Forest Park is one of the wildest parks in New York City. About the closest you can come to being out in the wilderness yet still within city limits.

I: Not Prospect Park?

SF: Prospect Park is very curated. Very thoughtfully, intentionally planned. You have these big fields. Forest Park is, well, it’s forest! I mean, we do maintain it—which I’ll talk about in a second—we get rid of invasive plants to help the indigenous plants and trees here thrive. But otherwise, it’s—well, it’s a walk in the woods.

I: It seems like being out in the wild is important to you.

SF: It is. I have become increasingly itchier—how to put it? I have become itchier and itchier the longer I live in New York City. I am so homesick for California. For trees and for soil and for… yes. Wilderness. So when I moved from Brooklyn to Queens right before the pandemic, I knew I wanted to check out Forest Park immediately. And when I did, I instantly fell in love. Is it California? No. But it’s as close as I can get and I love this place for giving that to me.

I: So you love this park. But more specifically you also love… plants? Trees?

SF: I read Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass during the pandemic. She writes a lot about reciprocity and being a good immigrant—because we’re almost entirely all immigrants in a new place, right? So that book got me interested in giving back to this place that I so appreciate. I wanted to have a sense of reciprocity—where I had a relationship with this land and the wildlife here, rather than simply taking. Rather than simply enjoying the park, I wanted to to help it thrive. So I started volunteering here. Helping get rid of harmful invasive plants and trees. Being a good immigrant. A good guest.

Which was also, of course, a good distraction during the pandemic.

I: Can you give an example of what sort of plants you get rid of?

SF: Sure. Look, right over there. You see those small trees? They’re vulnerable. They’re little kid trees—can’t take care of themselves. And see all that green? That’s English ivy. The ultimate colonizer plant. All that English ivy shouldn't be there. This is pretty bad, actually. I’m going to make a note to come back later.

I: How does the ivy hurt the tree?

SF: Well, large trees’ll be fine. They can handle it, but those little trees? The English ivy can strangle them and they’ll die before they can fully grow.

Also, here. This is Multiflora rose. Another invasive species that’s a big problem. It’s everywhere in the park—everywhere in New York City, really. Multiflora rose often works in tandem with some of these other crappy vines to take down trees. See that giant brambly thicket over there? And see that small tree? Those are all different vines taking that tree down. That tree is screwed.

I: I don’t think I knew there was so much… plant on plant crime? I mean, I’m aware of invasive species, but—

SF: No, they really fuck shit up. These plants can be vicious.

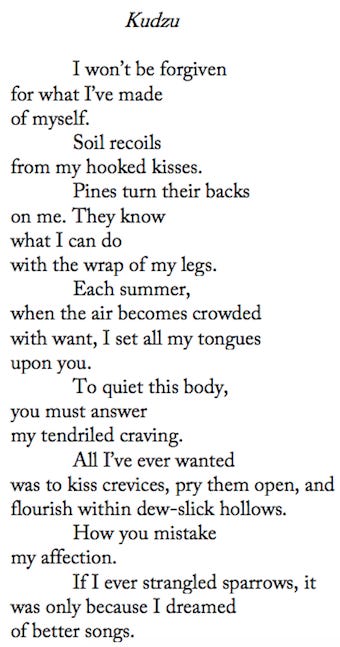

I: This is reminding me of one of my favorite poems: “Kudzu,” by Saeed Jones.

[Editor’s note: Saeed Jones—who also happens to be my best friend—has given me permission to share the poem in full.]

SF: Here, you see this tree? You see those sort of spiral scars going around it? That’s because there used to be vines trying to take it down, but somebody took care of that tree. Removed the invasive species that were trying to harm the tree.

In its own way, the spiral scar is beautiful.

I: You wrote a piece for New York Magazine about becoming—to quote the piece—a “Parks Department Super Steward.” You’ve been in New York for around eight years now, and moved to Queens right before the pandemic in early 2020. Can you talk a little bit about your nature journey in NYC before Forest Park came into your life?

SF: I used to live in Prospect Heights, so I'd go to Prospect Park a lot. Or I would force people to take me upstate sometimes, especially during the fall for apple picking. But really my relationship with nature in New York City was me constantly trying to grapple with the fact that there was no nature. In my head, there was none.

I basically felt, “Well, there are these weird parks that don't really feel like nature.” Sure, you're in a lovely park, but it doesn't feel like hiking in the Redwoods—something I did a lot when I lived in the Bay Area. So my “nature journey,” as you put it, was me coming to terms with not having a lot of nature in my life.

What I didn't realize then—but this is how I frame things now—is that everything is in nature. We are nature. To think that we are separate from nature is deeply, deeply flawed. Our street trees are nature. The weeds poking up out of the sidewalk are nature. Every green thing around us, every animal—be it a squirrel or a dog or a pigeon—everything is nature. We are nature. We are all part of this incredible ecosystem, and we get to shape it. We can, to a certain extent, affect the world around us. Realizing that, understanding that I have agency in that way, has been really empowering.

I: What helped you come to that realization?

SF: The aforementioned Braiding Sweetgrass, for sure. But it really started when I grew more curious about all the small plants I was seeing every day. Which is when I discovered this app called PictureThis. It’s not a very intuitive name, but the app itself is great. It’s a plant identifier app—you can identify anything: flowers, trees, herbs, leaves. It’s wonderful. So that’s when I really began to slow down and notice all the fauna around me. Another great book I picked up is Plants Have So Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask by Mary Siisip Geniusz.

By then I was living around here, so I started spending time in Forest Park and making friends with the gardeners and stewards. With their guidance—they would tell me if certain areas had been sprayed with pesticides or anything like that—and with the help of PictureThis and Plants Have So Much to Give Us, I began learning about all the benefits and medicinal purposes for common plants right here in the park. So I began to pick nettles, garlic mustard, wineberries, and other vegetation. Eating them on their own, or putting them in salads or cooking with them. I fell in love with interacting with my environment in that way. It’s truly, truly awesome.

I: Was this your first time experimenting with foraging? During the pandemic?

SF: Yes, this was all during the pandemic.

I: Do you have a favorite plant to forage?

SF: Wineberries are fantastic. I also made candied violets not too long ago.

I: Candied violets?

SF: I took some violets—the flower—and I candied them. Which is to say I dipped them in egg whites and then sugared them and then let them dry in my refrigerator for about a day. They’re purple and pretty and sweet and you can use them to decorate desserts or eat them on their own.

I also recently found some Chicken of the Woods.

I: Some what now?

SF: Chicken of the Woods. Edible mushrooms. Those were really good. Really chicken-y.

I: How did you prepare them? Did you eat them raw or—

SF: Oh, no. I made nuggets. Chicken of the Woods nuggets. Cut ‘em up and fried ‘em up. Delicious.

But more important than the taste is the feeling of reciprocity. With apologies for sounding like a West Coast hippie, there are these moments where it feels earned, you know? For example, I’ll spend a day clearing out a whole bunch of vines—forcefully ripping them out—and then I’ll stumble across an amazing turkey tail mushroom spot—or a bunch of Chicken of the Woods. That moment always feels like discovering a secret, and in a way it feels like the forest is saying, “Thank you.” So I say, “Well, thank you,” back, pick the mushrooms—or berries or whatever—and keep taking care of the trees.

I: So how did you come to be a “Parks Department Super Steward”?

SF: Well, I started out on my own. I was using the PictureThis app to look up plants, and then I would Google whether it was a native species or an invasive species. If it was invasive, I would rip it out. But turns out—surprise, surprise—that was a bit stupid. Because there are invasive species that aren’t all that harmful. Or, on the other hand, there are certain plants where—if you pick them—ten more will grow back.

I: Your heart was in the right place, but—

SF: But I had no idea what I was doing.

I: You were a plant vigilante.

SF: I was Spider-Man, completely fucking up the multiverse. But, luckily—and pretty quickly—I had the self-awareness to realize, “Someone should probably be teaching me, so I know what I'm doing.” Which is when I reached out to the Forest Park Trust. Now, I’m not gonna pretend like they got back to me right away. But I was diligent. I kept calling and emailing, and eventually they responded and said I could shadow a few Parks Department gardeners. That’s when I learned about becoming a Super Steward.

I: What does being a Super Steward mean?

SF: It means I have a certificate that allows me to work by myself, tending to the park, unsupervised.

I: What did the gardeners think of it all? Were they fine with you shadowing them, or were they wondering why you wanted to start helping—

SF: The first person I shadowed, who really taught me a lot, is this Russian woman named Irena. She’s really brass tacks, which was good for me. Very straightforward. “Here’s a vine. Here’s how you get rid of it. This is what you don’t do. This is what you do do. Now you try it.”

She had me doing hard, physical labor for hours every day. I was waiting for book edits at the time, so I figured, “Okay, I guess I'll spend some time pulling shit out for Irena.” The truth is, I really enjoyed it.

Oh look, somebody did a bunch of hard work right here. Not kidding, this might be Irena's work. All of this is Oriental Bittersweet. You can tell by the bright orange roots. That's a lot of digging and cutting someone did.

So, to answer your question, I don’t really know what Irena thought at first, but she saw that I worked really hard every day. And every day, I'd come back. That’s all Irena really cared about. She taught me about soil pH, and all the different types of trees and plants. She was also really good at identifying birds, so she taught me about all the different species of birds that live in the park.

Eventually she started trusting me on my own, giving me a pair of pruners and sending me off.

Then I met Mike, another gardener I shadowed. He would talk to me the whole time—teaching me things about the park, sure—but also telling me about his travels around the world, all the languages that he spoke. Like Irena, he’s also really into birds, so he taught about all the different bird calls. Always stopping mid-project, “Here, do you hear that? There’s a meowing. That’s a catbird.”

Mike and Irena both have different caretaking styles. Irena goes hard on removing invasive plants, and Mike goes hard on nurturing native species. Which is really nice, in a way, because I think you need both. I feel really lucky that I got learn from both of them.

I: Are y’all friends?

SF: Yeah. I’ve been to a party at Mike’s house—it was all people who love plants. Mike loves plant people. Same way there’s a music scene in New York City—and a fashion scene, and a drug scene—there’s a plant scene. A whole community of New Yorkers who really care about plants. Both Mike and Irena are really nice to me. They like having me around, I think. Mike even came to my last birthday party. He brought me an orchid.

Watch out, there’s some poison ivy over there.

I: Will you rip that out later?

SF: No. Poison ivy is good. You see how it doesn't choke the tree—it simply goes up alongside it. That's the difference.

Wait, be quiet a second.

I: What’s that?

SF: Birds.

[Editor’s note: This is when the aforementioned meeting with the bird photographer took place.]

I: Holy shit. What is this?

SF: This is a bird thicket.

I: There’s so much movement around us. Goddamn. That tree alone. There must be a million cardinals.

SF: Maybe not a million, but yeah. If you look closely there are some woodpeckers, too. Maybe two—no, three! Three species of woodpeckers.

I: This is incredible. Right here in Queens.

SF: Right here in Queens.

I: That was amazing. I understand what you mean now, how this park really feels like wilderness.

So, while you are helping the park and the local wildlife, is it safe to say you get something out of this too?

SF: Protecting trees isn't altruism. It's a form of self-care. Like I said, reciprocity. By helping trees we are helping ourselves. Trees clean our air, they help prevent global warming. Areas where there are fewer trees have much higher rates of depression, much higher rates of asthma. By tending to trees we are literally caring for these incredible plants that take care of us. And it isn’t only trees. There are so many studies that show the more time we spend in nature the happier we are. Our cortisol goes down, our blood pressure goes down.

Did you know that dirt makes you happy? There’s a microbe in dirt—Mycobacterium vaccae—and it’s been found to have a similar effects on our neurons as Prozac and similar drugs. All you have to do is breathe it in—smell it—and it fucking makes you feel good. So when I'm digging in the dirt, I'm literally making myself feel better.

Another thing I think about a lot is loneliness. It’s something that’s really hard about New York. You can be surrounded by people but not know anyone. But if you take a bit of time to care for a tree? Then, for better or worse, you and that tree have a relationship. Even knowing how to identify different plants—you aren’t simply walking by a bunch of green things, then, but instead you know the plants by name. I can’t really explain it, but it makes me feel a little less alone.

Take the London plane, for example. One of my favorite trees. The New York City Parks Department logo is based on a London plane leaf. Anyhow, the London plane is a tree that removes tremendous amounts of carbon monoxide out of the air—pounds of toxins every year. The tree puts the toxins in its bark and then sheds the bark off. Every time I see a London plane, I acknowledge the work it’s doing for us, “Hey buddy, thank you. Thank you for helping keep this city’s air clean.” Simply by recognizing the tree—by being able to tip my hat and say thanks, that makes New York City feel less lonely to me.

I: Your memoir, What My Bones Know, came out this year. Tell us about it.

SF: I was diagnosed with complex PTSD in early 2018.

I had known I struggled with anxiety and depression, but I didn't truly understand the depth to which it affected my body, my brain, my future, my past, the way that it was manifesting in relationships. All that shit. So, after my diagnosis, I Googled “complex PTSD” and it seemed pretty serious. I'd always taken my anxiety and depression for granted, thinking, “C’mon, anxiety and depression? Everybody's got some anxiety and depression, right?” But then I read about complex PTSD and I realized, “Oh no, I have something much more serious that I need to seek treatment for.”

So—sorta like with plants, actually—I started reading all these books about complex PTSD, which were really depressing because they were so pathologizing and so stigmatizing. They were all saying that I was difficult, that I was a burden, that I had trouble maintaining relationships and was aggressive and prone to addiction. That I was a bad person, or at least that’s how they read to me. The list went on and on. Which was all very stressful. I hated that it was so hard to find a book with real solutions, a book that was written by someone who actually had complex PTSD, a book that was, well… kind.

Around then I started Googling celebrities with complex PTSD, because I understand the power of storytelling. If I could make complex PTSD more personable—more relatable—maybe I had a better chance of understanding it. Because this is what I did at my day job back when I worked at This American Life. I worked to destigmatize various issues—veterans coming home from war, for example—through stories. So I tried to find any type of story relating to complex PTSD that could do that for me, but there were so few out there.

I remember thinking, “If I can't find these stories, I’ll have to make the story myself.” When people are first diagnosed, they go down this rabbit hole—the exact same way I did—and it feels really crappy. I want there to be a book that people can read and feel, “I'm not alone. I have hope. It's going to be okay.”

So that’s the book I set out to write.

I: That's incredible, and congratulations on accomplishing your goal.

SF: Thank you.

I: You just brought up your long career in, how would you say it? Radio? Podcasting? Audio storytelling? Do you approach writing and, say, a piece for This American Life differently?

SF: There are similarities, sure. One, you have to make certain you have the ingredients for a great story, no matter the medium.

When I’m making a radio story, it isn’t simply, “Thought. Thought. Thought.” It has to be, “Thought. Scene. Thought. Scene. Thought. Scene.” It needs to be cinematic in a way. So I set out to do the same when I was writing the book. All while maintaining a narrative arc of going from a place of utter despair to a place of feeling at least a little bit of hope.

But complex PTSD doesn’t really care about your narrative arc, right? Healing isn't linear—it's ups and downs. And sometimes downs and then more downs. So I worried about that. “Oh no, is the reader going to be frustrated at me for falling into a pit of despair after all this healing that I've done at this point in my book?”

But the truth is the truth, and you can’t shy away from that.

I: It’s almost as if you approach the two mediums in similar ways, but instead of diving into somebody else’s story the way you would for This American Life, you’re diving into your own.

SF: Exactly. Which I then of course worried was extremely narcissistic, but I learned to say to myself, “You spent ten years telling other people’s stories—interviewing hundreds, maybe even thousands of people. It’s ok to focus on yourself a little bit.”

I: Do you find it hard to give yourself the same care? The same tenderness—or the same understanding—that you give to someone when you’re working on their story?

SF: Yes. But I keep trying.

I: Now that you’ve written a book, are you still going to do work in the audio space?

SF: I’m not sure. That’s one real difference that I enjoyed while working on the book—there's a lot more spaciousness. A lot more time. I think What My Bones Know is the most impactful story I’ve ever told, and part of that is because I had more than a week or a few months to work on it.

I: You gave yourself time to figure it out. One might say your entire life.

SF: Which was important. But I don’t think I have to choose. I think I can do both. That said, I would like to move at a more bookish pace when working on audio in the future.

That’s the big lesson I've learned—much like your whole “time millionaire” deal—I don’t want to rush things. Don’t want to push things out simply for the sake of pushing things out. Maybe paradoxically, at the same time, I want to have a more laissez-faire attitude when it comes to my work. For a lot of my life in a lot of the different jobs I’ve had, there’s always been an extremely high attention to detail—perfectionism all the way down. That’s something writing a book teaches you, I think. You can tweak it and tweak it and tweak it for fucking ever, if you want. You can spend your whole life rearranging the words on the page, but at a certain point you have to say, “You know what? This is good enough.”

I: I love the idea of moving at a bookish pace. That said, audio is a sector that continues to explode. And I’d argue you were very much at the forefront of that explosion—you began working in audio at a very young age. There are obviously a lot of young people now who are interested in getting into audio. Would you have any advice for them?

SF: I would say make stuff. Make your own stuff. If you make your own stuff, that gets the attention of people who might hire you because they're thinking, “Whoa, this person is a go-getter. A self-starter.” Plus you learn a lot, too. Working in a vacuum can be really helpful in terms of finding your own voice. You're not getting that good editing help—which eventually you'll need, of course—but at the same time, I think it's important to find your own voice before you get too polished.

So many people in audio try to emulate success. They want to sound like Ira Glass or Ari Shapiro or Joe Rogan or whoever they listen to. But I think one of the benefits of podcasting in this moment is it's becoming more and more diverse, which means there are always new markets. So it’s beneficial for you to figure out how to sound like yourself first. Then find the polish. Your people will find you if they like your voice. They’ll find you if you’re authentic. Your audience will come to you.

If you’re in the beginning of your career you have the freedom to fucking be weird, so I recommend doing that as must as possible, too. When I first started I was so weird, trying out all sorts of things. I don't feel I can be as weird anymore, but if you’re early on in your career you have the opportunity to experiment and try really daring things. So do it. Use weird sound effects. Take wild risks. Go nuts.

Oh wow, Look at this burl.

I: This what?

SF: This, it’s a burl.

I: B-U-R-L?

SF: Yeah.

I: Apologies for being so tree ignorant. What causes a burl?

SF: It’s a fungus that gets under the bark, almost like a cancer.

I: Oh no. Sorry, tree.

SF: It’s ok. It doesn't necessarily kill the tree.

I: The tree’ll be fine?

SF: Almost certainly.

I: This feels a big question, so please feel free to say, “Pass, asshole.” But what have you learned about living with complex PTSD?

SF: I think one of the most important things I've learned is that it's not all bad. There's a lot of really bad things about complex PTSD, let's not get it twisted. It fucking sucks. But at the same time, my trauma does not make me broken. My trauma does not weaken—well, in some ways it weakens me. But in other ways it strengthens me. It's important to be able to focus on those strengths.

When you get diagnosed with complex PTSD or conditions like it, you look at the list of symptoms and it’s always one long list of negatives. Always. For example, a symptom for autistic people is “aggression,” but never “increased creativity,” even though that’s something many autistic people have.

When you have complex PTSD, you tend to be really calm in a crisis. People with complex PTSD are often incredibly empathetic. Complex PTSD is, well, complex. So that’s something I’ve learned. I’m not simply a list of negative attributes. There’s more to the story.

I: That’s beautiful. Do you find it encouraging that more people are aware of mental health issues than they have been in the past? That we’re seeing them as more complex issues?

SF: I’ve been in and out of therapy since I was 19, so it’s encouraging to see how much growth there’s been over time. There are so many more conversations than there used to be. It wasn’t until very recently that we even began to accept that people who haven’t been to war can experience PTSD. Which, quite frankly, was really, really sexist—especially because woman are more likely to develop PTSD than men.

I write in my book about the word "trigger" and how people always think being triggered means that you're being sensitive. That you're a snowflake. That you have this horrible PTSD. None of that is true. Everyone gets triggered—it's a human response. Trauma responses are human responses. It's literally your brain trying to keep you alive. If you go through something traumatic, or even difficult, your body encodes it as danger so that the next time something similar happens—regardless of whether you are or aren't in danger—your body might have a freak out or get anxious or have any number of responses.

For example, if you had a gnarly breakup and you have difficulty dating again, that's a total normal human response. That's not complex PTSD, necessarily, but it's going to be freaky and that is being triggered. It doesn't necessarily mean that you're going to have a full body shutdown or a panic attack. What it means is that your body and brain are not matching up with the reality of the situation.

So being able to normalize that and say, “Ok, I'm having a trauma response right now. That doesn't mean I'm going to shut down this conversation. It doesn't mean I'm too weak to continue. It means that I need to do what I need to do to get my brain and body back online.” So maybe that means I need to breathe deeply or eat a sandwich or take a drink of water or take a five minute break or whatever it is to make sure that my brain and the reality of the situation realign. That's healing from trauma. And that's not that big of a fucking deal. We don't need to equate experiencing trauma with victimhood, necessarily, but we do need to give people the resources to be able to heal. So we need to acknowledge the power and impact that it has on people without stigmatizing it.

I: So that people feel comfortable seeking out treatment, or at the very least saying to themselves, “Hang on. There might be a reason why this is the way I'm reacting to these things.”

SF: One of the most rewarding things that's happened since my book came out is people saying to me, “I don't have complex PTSD, but I still learned so much about my own brain and the way that I deal with things because of your writing.” And I'm like, "Yeah, because we're not that different. Great.”

I: You don't have to have complex PTSD to say, “Oh, I recognize certain behaviors and this is why I act this way. And maybe there's something here for me to dig into and work on.”

SF: Precisely.

I: Apologies if this is a bit of a bummer question, but does your vigorous interest in the environment also come with a whole new set of worries? Put another way, do you have any hope regarding environment and the current moment we’re in?

SF: Have you read The Overstory by Richard Powers?

I: I have not.

SF: I think The Overstory is really helpful in terms of talking about time—speaking of a bookish pace. The ultimate bookish pace is trees, right? The pace of trees is super, super slow. When we’re talking about trees we’re talking about decades, centuries, eons, even millennia.

When I think about nature, I realize that a lot of what is happening is about us—is about our impact. But a lot of it is not about us. We are not the center of nature. We are simply a part of it. Nature is going to continue, whether we wipe ourselves out now or later.

So The Overstory was really helpful for me in terms of realizing how insignificant we are. But then again, in Braiding Sweetgrass Robin Wall Kimmerer writes about how nothing gets done in despair. You must have hope in order to accomplish anything. Which I think is true for complex PTSD or trauma, as well. Same as when thinking about the environment. You have to maintain hope. You can't get frozen by despair.

Now that doesn’t mean you can’t spend some time wallowing in it, but eventually you have to find your hope. That’s true for healing from trauma. It's true for healing from the horrors of climate change. It's true for healing from anything. You need that time to wallow a little bit, to feel your feelings, to feel a legitimate anger and sadness, but through it all, you have to have that hope because nothing is achieved in despair. Once you have that hope, you have that resolve to say, “Ok, I'm going to fix this. I'm going to learn how to talk to people. I'm going to learn how to calm my body down. I'm going to go out into the park and rip up some vines. I'm going to compost, join my local birding community. I’m going to live.”

So I guess that's what I try to keep in mind.

We walk back to Stephanie Foo’s car, all the while talking about San Francisco—where we first met. We swap memories of our old friends, and the events we used to attend together, Stephanie usually with a microphone in her hand, recording the reading or comedian or musical act. The sun has sunk low in the sky, and the cold air cuts through our large, winter coats. Her car is a welcome refuge, especially once the engine starts and the air around us begins to warm. Foo steers the vehicle toward the boarder of Queens and Brooklyn, as we commiserate about missing California’s climate.

Not long after Stephanie pulls her car up to the curb at Liberty Avenue Station and we hug goodbye. I think, for a moment, about walking home. The project is called Walk It Off, after all. But even with my sleeves pulled up to cover them, my hands are frigid. Stephanie drives off as I make my way down the steps of the subway station. I try not to be too hard on myself.

Such timing! I finished What My Bones Know two days ago. It was such an incredible book-- so gorgeously written; so inspiring; such a very important read. And I loved so much the setting of this talk. Trees and forests were so instrumental in my own healing, in no small way because of what Stephanie mentioned above about both their slowness and the way that we, as nature-beings ourselves, are intimately connected to them. Truly truly a beautiful conversation-- thank you again and again for letting us all tag along.

That was wonderful, thank you (and thank you to Stephanie Foo).

My public library has What My Bones Know, so I'm going to check that out soon.

And if anyone reading this isn't in a position to buy the book or can't find in a local library, see if your local library offers Interlibrary Loan.

If they do, you can request the book and get it for free!

Thanks again for that wonderful post.