A Walk Through the East Village With Ada Calhoun

"The truth is always better. That’s something I believe. Even when the truth is terrible, the truth is always better."

“My ma died in February.”

Ada Calhoun and I are at the International Bar in the East Village, and I’m telling her the specifics of my mother’s death. The afternoon is gray and rainy, but the day-drinkers around us are jovial, and the Guinness I’m sipping warms my chilled bones a bit. Ada kindly listens while I talk, she herself having lost a parent in October of 2022—which, if I’m being honest, is probably why I called her to ask if she wanted to go on a walk. Reaching out to somebody who might, in some way, understand.

But Calhoun is also a New York native, a species of person I find fascinating, and I’ve been wanting to walk with her through the neighborhood of her youth—where she also currently lives—for some time now. So, after another Guinness or two, neither of us in a rush to get out into the wet, cold, early Spring day, I finish what I have to say about my ma for now, and Ada and I pay our tab and set out on foot.

Ada is smart enough to have brought an umbrella, which she offers to share with me, but I decline, the damp somehow a comfort.

Isaac: So why are we starting at the International Bar?

Ada Calhoun: Well, it was one of the only bars nearby open this early, for starters—and it’s one of the bars I drank at as a teenager. I like that it’s still around, that it’s still exactly the same bar as it was back when I was growing up.

I: You were a born and raised Manhattanite who drank here as a teenager. Did they not check IDs? Did you have a fake ID?

AC: I’ve never had a fake ID in my entire life—I mean, I didn’t have a real ID for a long time, either. I didn't learn how to drive until college.

I: So you grew up in this area?

AC: I grew up on St. Mark's Place between 1st and 2nd Avenue—and I’m living there again, now.

I: Do you think New York City was more fun when you were growing up?

AC: I’m hesitant to agree with that. So many people are always saying, “Oh, the city used to be so good. It used to be so fun.” Most people who say that aren’t even from here. They’re comparing New York now to a New York they’ve dreamed about or read about. Secondly, so much is still the same. The International Bar is a great example.

I: I mean, they’re better at checking IDs now.

AC: Sure, but other than that it is exactly the same. Same with Holiday Cocktail Lounge, Tile Bar, B&H—the kosher lunch counter that’s been open since 1938—Blue & Gold Tavern, Veselka. The list goes on and on. There’s still a lot of the city that I grew up in. It’s still here.

I: Is it safe to say that what you’re talking about is a… sort of philosophy for you?

AC: How do you mean?

I: I’ve thought about this a lot—I even write about it in Dirtbag, Massachusetts. When I was living in San Francisco in the aughts, people were like, “Oh, you should have been here in the 90s. You missed it. That's when the city was really happening.” But now when I go back to visit, people are like, “Wait. You were here in the aughts? What was it like? I hear that’s when the city was really happening.”

AC: Listen—and I’ve said this before. Everybody has a year that the city was good, and then the city was never good again after that. Usually, that time is when said person was 19 or in their early 20s.

I: When they were young?

AC: When they were hot. Whenever a person was at peak hotness—

I: With the least amount of responsibilities—

AC: Exactly. “Oh, there was an era when cool people would simply talk to you on the street, and you’d be invited to parties in warehouses that nobody else knew about? So you miss 1994?” No. You don’t miss 1994. You miss how good you looked that cool people talked to you on the street and invited you to parties in warehouses that nobody else knew about. You don’t miss the ‘70s. Or the aughts. Or the ‘80s. You miss that time in your life—

I: When you looked good in a halter top—

AC: Or in your baby doll shirt. Or when you were young enough to be a hot, confident skateboarder. Or to look hot reading books in bars. It goes on and on.

I: Did you always want to be a writer? Growing up in Manhattan. Going to bars in your teens. Did you—

AC: No. I wanted to be a farmer. Or a translator. I had a very domestic fantasy of sitting in a cozy farmhouse reading books all day.

I: Did you dream of not being in the city?

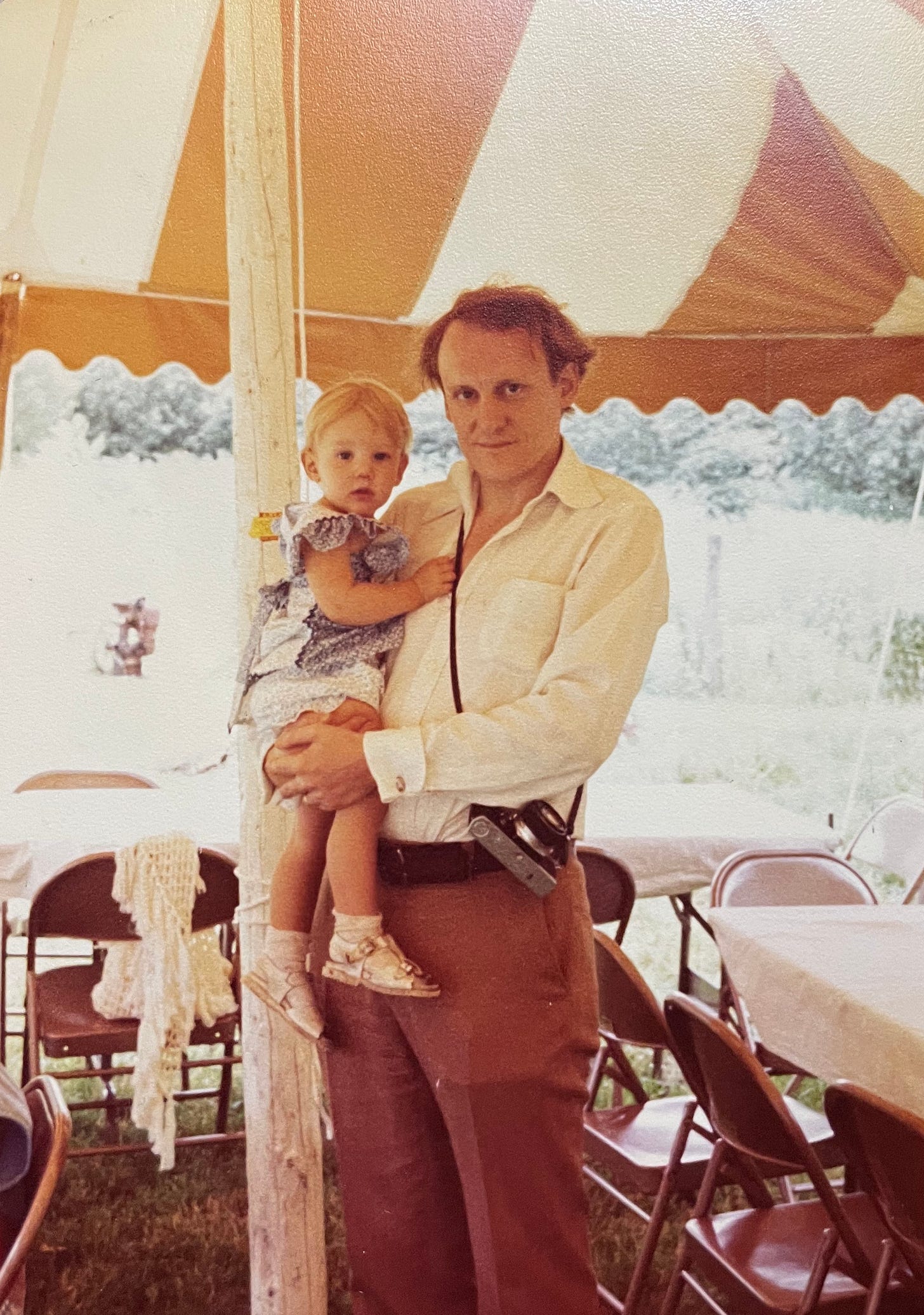

AC: Yes. I wanted to live in the country. I wanted to do manual labor, while also having time to read a whole bunch. That was my idea of heaven—not writing—reading. I didn’t want to be a writer. My father and all of my father’s friends were writers—and I did not want to be like my father. Writing was his job. So I avoided it. Strenuously.

I: Readers who are familiar with Also a Poet will know, of course, but for those who aren’t, can you tell us a bit about your father?

AC: He was an art critic named Peter Schjeldahl, who was very revered in the art world.

I: So you grew up surrounded by that world—but your dream was, “What if I milked cows?”

AC: Not so much a dairy farmer, per se. More that I was growing plants, while having time to—

I: To read.

AC: Correct. There was a book I found at a used bookstore when I was young called A Flatland Fable by Joe Coomer—do you know that book?

I: I do not.

AC: Oh, I love Joe Coomer. I’ve read everything he’s written. A Flatland Fable is this tiny little book about a day in the life of this guy who lives in a small town and his wife’s pregnant, I think, and his father’s dying. Anyway, the book is so beautifully written, and I remember reading it and feeling, “That’s it. That’s what I want. I want the exact feeling that’s so alive in this book.” And that feeling involved neither writing nor living in a city.

I: So when’d you fuck it up?

AC: I mean, there’s still time, Isaac. I can still get out of this. It’s not over.

I: Fair enough, but you are—currently—a writer living in New York City.

AC: Yes.

I: Did you go to college here in NYC?

AC: Well, first I took a year off after high school and traveled and did some manual labor.

I: You brought it up, so now I have to ask— especially with you growing up here in Manhattan—where’d you go to high school?

AC: Stuyvesant.

I: Ok, so you went to Stuyvesant and then you took off a year to go learn that farming ain’t all it’s cracked up to be—

AC: Not true. I loved reading on trains and pruning trees and having European boyfriends and all of it.

I: Then you came back and went to college where? In New York?

AC: No, I went to McGill for two years.

I: Harvard of the North. By that point were you interested in writing? Or in journalism?

AC: No. At that point I was interested in translation.

I: What’d you want to translate?

AC: Sanskrit.

I: Sanskrit?

AC: Sanskrit.

But hold on, this is one of the things I wanted to show you on our walk. Do you know this statue?

I: I don’t. To be honest, I don’t know where we are. Where are we?

AC: We are in Tompkins Square Park and this is a Temperance Fountain. In the late 1800s and early 1900s there was this craze for temperance and a real organized attempt to get everyone to stop drinking—and one of the strategies of the temperance movement was to make fresh drinking water widely available, in hopes that everyone would drink nice, cool, clean water instead of alcohol.

I: Often people were drinking beer because the water was contaminated. Beer was safer.

AC: Hence the temperance fountain.

I: What does it say on each side?

AC: Temperance, charity, hope, and faith.

I: So you traveled and worked before college?

AC: Yes, I traveled quite a bit. I did manual labor in Switzerland, and then with my cousins in Norway. I traveled through India for three months and did volunteer work.

I: You volunteered at Mother Teresa’s mission, correct?

AC: I did. But here’s something else I wanted to show you. The Slocum Memorial Fountain. Do you know what the greatest disaster in New York City history was before September 11th?

I: I mean, I have a guess now—but no.

AC: So this entire neighborhood used to be all German immigrants. There were these large, German families, and they used to participate in these big church picnics—getting dressed up in fancy clothes and spending time together. Every year they would charter a ship and sail up the East River to go picnic.

Then, in June of 1904, close to 1,400 passengers—many of them women and children—boarded a paddle steamer called the General Slocum, and while en route to Locust Point in the Bronx, the boat caught fire and sank. About a thousand passengers died—

I: Jesus Christ.

AC: It’s the worst maritime disaster in New York City’s history and—

I: The worst overall disaster in the city’s history until September 11th, 2001.

AC: Correct. There are many theories as to what happened. One is that the captain was drunk and—after the boat caught fire—he sailed into the wind, thereby stoking the flames.

But the general consensus is that the boat wasn’t very well maintained. Plus all the life preservers had rotted. Also the women were all in these enormous, heavy dresses, making—

I: Swimming rather difficult—or, to put it another way, sinking rather easy.

AC: As I recall, the disaster eventually contributed to the fall of Tammany Hall, because people realized that the safety inspectors had all been bribed. It helped expose all this massive corruption in the city.

But it was also the end of Little Germany. The end of this neighborhood mainly being German immigrants. The whole area was gutted. Full classes of children—as in, say, a kindergarten class—were just gone. The funeral processions were huge. I have a really beautiful, horrible picture of a street full of hearses. The entire community was decimated, and, on top of all that, most anyone who survived decided to move, anyway. It was simply too sad to live here.

I: Terrible.

AC: Here’s another landmark. Do you know why this tree is special?

I: Hang on, Ada—let me process the boat disaster! But no, I don’t know why this tree is special.

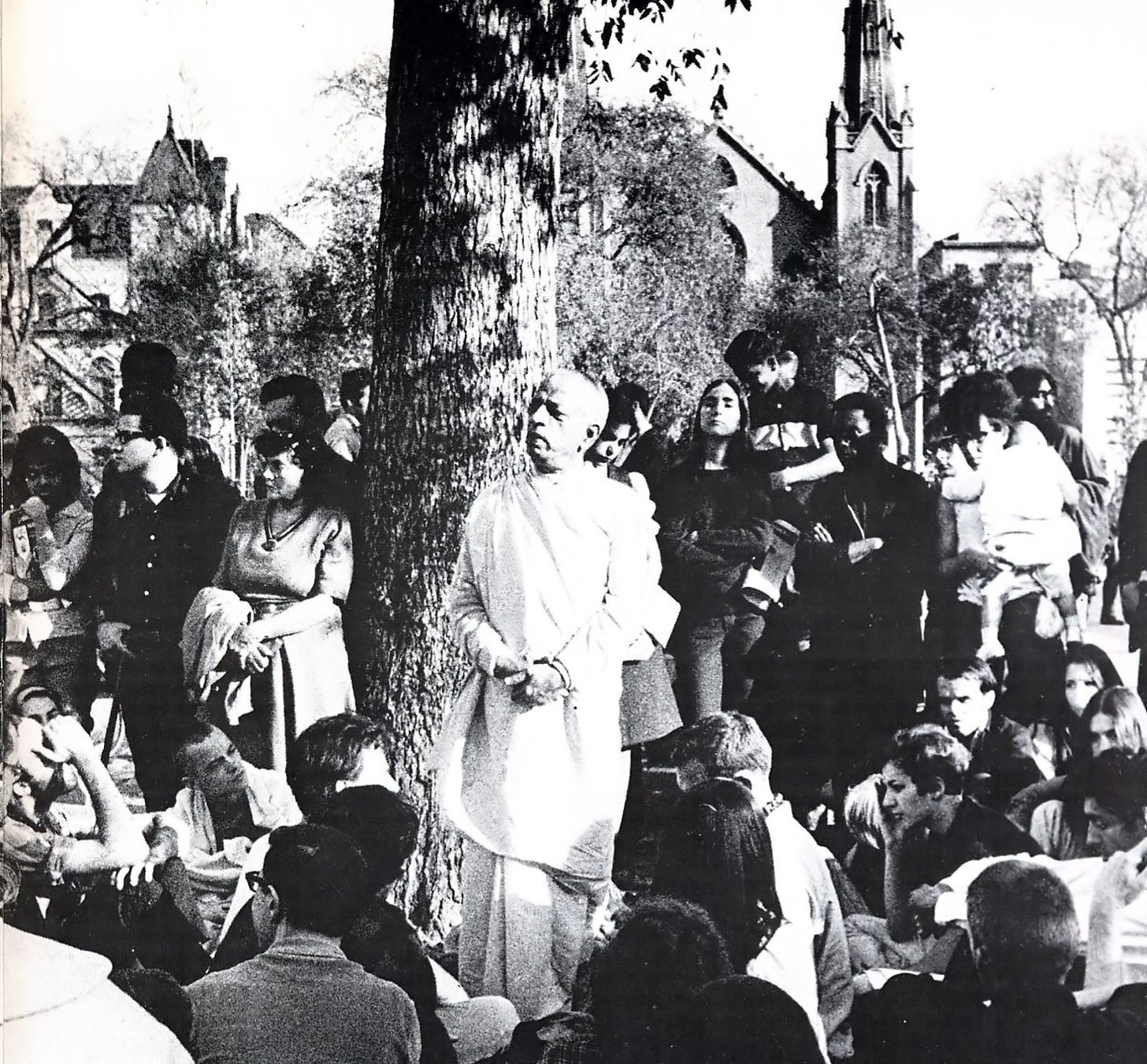

AC: This is the Hare Krishna Tree. In the mid-1960s Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada—the spiritual leader who helped spread the Hare Krishna mantra—came to this tree and, along with his followers, held the first outdoor Hare Krishna chanting session in the United States. I think it was the first one outside of India in the whole world, actually. Allen Ginsberg was here. It was a whole scene. I have a photo of that, too.

I: So would you come to this park a lot as a kid?

AC: Not so much. There used to be a lot of violence in the park. One friend of mine growing up—the first time she ever saw people having sex was a couple who were apparently living in Tompkins Square Park.

I: Not exactly kid-friendly.

AC: No. A child who I used to babysit found a loaded gun in the sandbox here once.

I: What? That’s like a New York Post story come to life.

AC: There was also Daniel Rakowitz.

I: Who’s Daniel Rakowitz?

AC: In 1989 Daniel Rakowitz killed his girlfriend—some people say it was a his roommate, not his girlfriend—but either way he murdered her and dismembered her and then cooked a soup using some of her body parts and fed the soup to the unhoused people who were living here in the park.

I: Uhhhh, what?

AC: He tasted the soup himself and claimed he was a cannibal for the rest of his life. You didn’t know about that?

I: No, I’m sorry, I didn’t know Tompkins Square Park had its own Sweeney Todd. At the risk of sounding squeamish, is there something else to show me without so much tragedy and mayhem?

AC: Sure. Do you like witches?

I: Who doesn’t like witches?

AC: Here, I’ll take you to the witch store.

I: When did you start getting interested in writing and journalism?

AC: Well, it turns out there aren’t a lot of day jobs that require Sanskrit translation skills, and I needed to make some money. I had done a few internships at magazines when I was in high school, jobs I had gotten because I also babysat for many editors and writers.

I: Friends of your father?

AC: More just friends of the family and people we knew in the neighborhood. So I’d often start out babysitting and then move into an assisting/intern role at the magazine. So I was working at Esquire and Spin—

I: When you were in high school?

AC: Yeah, when I was 16 or so.

I: So when you came back from McGill you started working in magazines?

AC: No, I worked there when I was still at Stuyvesant. By my senior year I already almost had enough credits to graduate so I took a light schedule of classes and worked a lot during the week.

I: Ada, goddamnit.

AC: What?

I: I’m sorry. I’m a stickler for a timeline. You come back from McGill—

AC: I went to Massachusetts and worked on a farm with my Canadian then-boyfriend.

I: Not more farming.

AC: Yes, more farming. Then I decided I wanted to go back to school.

I: So you hadn’t graduated from McGill.

AC: No. But I had been offered in-state tuition from the University of Texas at Austin when I was originally applying and so I reapplied as a transfer student to see if they’d still give that to me and they did.

I: Hook ‘em horns.

AC: So I transferred down to Austin, where I went to school for two more years. I graduated from UT Austin in 2000. When all was said and done it took me six years to get my undergraduate degree.

I: But you were working the whole time—or taking time off to farm.

AC: I worked at so many different places, but eventually I ended up working at The Austin Chronicle, because I couldn’t find any Sanskrit translation jobs and—

I: So that’s how you came to journalism.

AC: Yes.

I: You already had clips because of your magazine work in high school, but you started getting serious clips while working at the Austin Chronicle?

AC: Correct.

I: I’m going to regret asking this, but what’d you love about Sanskrit?

AC: I still love Sanskrit. I think it’s the best language. The way it’s constructed is so interesting. It has so much grammar. So I kept taking classes—and then graduate classes. “This will be the rest of my life,” I thought.

But then the work at the Chronicle became more and more interesting. I started writing as one of the paper’s theater critics, which is when I changed my name—

I: Was it important to you that nobody knew you were your father’s daughter?

AC: Well, in New York City he was very famous—or at least it felt that way to me, right? Outside of New York, though? I didn’t know. But I figured, “Better safe than sorry.” Also, I didn’t want people to associate us.

I: How do you mean?

AC: I didn’t want people thinking I was getting work or whatever because of him, especially because I wasn’t. So I figured I’d simply use my middle name as my last name while writing for the Chronicle. Also, that way he and my mother wouldn’t necessarily hear from people what I was doing. People wouldn’t know we were related.

I: Wouldn’t be able to keep tabs on you, I understand that. Was it also a way of setting out on your own—is that fair to say?

AC: Nailed it.

I: So where’d your middle name come from? Calhoun?

AC: Elizabeth Calhoun Baker. She was an editor at Art in America. Baker was a friend of my parents. I was born on St. Patrick’s Day, and my parents thought her name was Irish. But Calhoun, it turns out—

I: Is Scottish.

AC: Very good. Calhoun is Scottish, which my parents learned when they called her to tell her the good news.

AC: This witch store—which is called Enchantments—used to be at a different location, but it’s been around since I was a teenager.

I: Good to know that an honest witch store can still make it in this town. So when do you come back to New York after your time in Austin?

AC: 2001.

I: And what are you doing for work?

AC: I worked in photo labs. That was my big day job for a long time—both when I was in Austin and then here in New York—my fallback if I couldn’t get work writing or editing.

I: Developing film?

AC: Developing film and making custom prints.

I: Sadly not as dependable a job as it once was. The witch store perseveres, even as the film labs go out of business.

So you’re returning to NYC in 2001. Where have you worked at—or written for—up until this point?

AC: Let’s see, I worked at a bunch of magazines in high school, like I said. Spin, Esquire, and World Business. Then in Austin I worked at the Chronicle. Then when I moved back to New York I did photo labs and then worked at Vogue as an editorial assistant. Then I went to New York Magazine as the theater listings editor.

I: What’d that entail?

AC: Doing blurbs for shows, managing the listings, and then doing three or four mini-profiles or mini-previews every week. So I was watching a lot of theater at that time—like sometimes six Broadway shows a week—because I had free tickets to everything.

But I kept pitching story ideas to other sections of the magazine and never getting any of my pitches accepted, so I left and took a job at the website Nerve.com, where I was a culture editor for a while, and then a deputy editor and then, eventually, they spun-off a parenting site called Babble and I became the editor-in-chief there.

I: Back in 2012 when I was 28 or so Nerve listed me in a piece called “Meet Your Favorite Websites' Most Eligible Single Staffers,” which I appreciated at the time.

AC: I was gone by then, but I’m happy that worked out for you. I left Babble in 2009, and, well, I’ve basically been a ghostwriter as my day job since 2009.

I: Ghostwriting—also more reliable than photo labs.

AC: I would still take small jobs here and there. I worked at the New York Post crime desk for a few months—

I: Wait. What was working at the New York Post crime desk like?

AC: It was a reporting job to make some money.

I: No. We are not smoothly moving past this, Ada. What the fuck was it like working at the New York Post crime desk for a year? For the record, that’s my go-to news source for all things related to the Gilgo Beach serial killer—and really all serial killer news, in general.

AC: It was a great experience for me. Before that, I hadn’t done much boots-on-the-ground reporting. I wasn’t used to getting doors slammed in my face, or people hanging up on me.

I’d been doing a lot of arts reporting before that, and people are usually happy when you show up as an arts reporter. But when there’s crime involved, for numerous reasons, the person you’re trying to get a quote from might not be so willing to talk to you. So I would work all day trying to get quotes from people—suspects, lawyers, law enforcement, witnesses—and that was a really good experience for me. Good training.

I: A PR person for a theater production will make celebrities available to you for quotes, whereas—

AC: Here I had to gather quotes, and really figure out what the story was. With a play, you’re covering the play, right? But with crime, there are so many different moving pieces that you have to figure it all out, and you have to try really hard to not get it wrong. The stakes are higher. There’s more pressure.

Before working at the New York Post, if you’d asked me if I was a reporter, I would have said, “Yes.” But looking back now, I don’t think I was actually a reporter until that job.

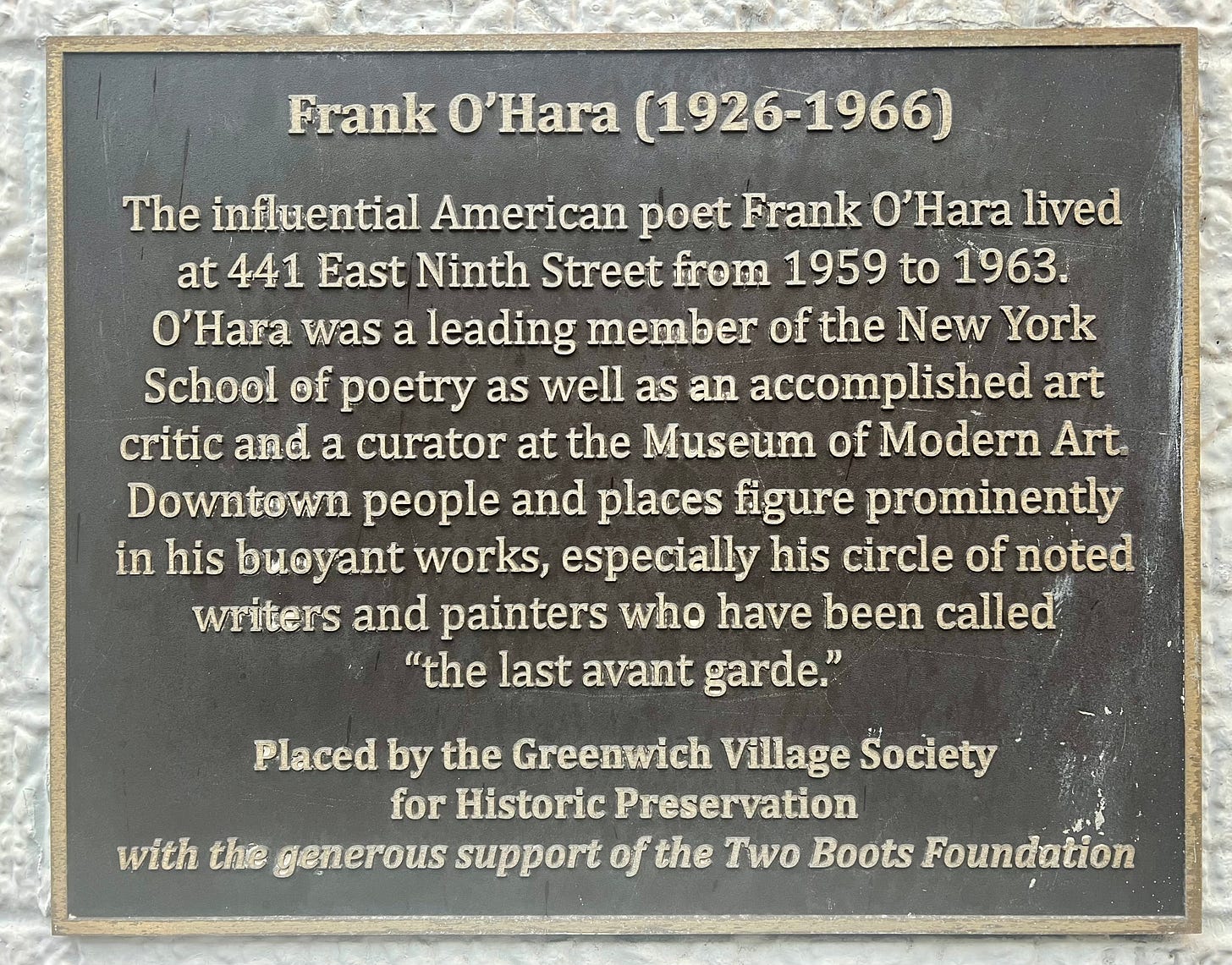

Do you want to see where Frank O’Hara used to live? It’s a poke place now.

I: I will not be distracted by the uncapturable meaning behind Frank O’Hara’s old apartment building now being a place called Poke & Roll. Tell me a story about your time at the New York Post.

AC: A story? Ok, one time when I came into work the managing editor was so happy he was crying. So I asked, “What’s going on?” And he responded, “Russian spies were arrested last night.” I remember thinking, “Ok? Do we like spies? What’s so special about spies?” The managing editor must have seen a quizzical look on my face, because he got sort of exacerbated and pushed on, “Ada. Look at her. Look at the spy.” He then held up a photo of what could only be described as a very, very sexy spy, “Look at her!”

So I said, “Oh, that’s great. I’m so happy for you—”

I: Meanwhile he’s probably thinking, “You don’t get it! This is New York Post gold!”

AC: He really did. He kept going! “No, Ada. You don’t understand, yet. Look at her. Look at the color of her hair.”

I: What color was her hair?

AC: It was red, which is what I said, “It’s red.” And he kept going, “That’s right. It’s red. Red, Ada! Do you know how many headlines we are going to get out of a hot, red-headed, Russian spy?!”

[Editor’s note: At this point I have stopped walking because I am laughing too hard.]

I: That’s so beautiful. This is such a gorgeous New York Post story.

AC: Well, there’s an epilogue. Because my first job that morning was to hit the phones and start doing research on the internet to try and find out everything I could about this sexy, red-headed Russian spy, right? So, later that day, I walked up to my managing editor and got to say, “Guess what? She’s got a sister.”

I: No!

AC: He practically started crying all over again. I’ll never forget, he said, “God bless you. Do you want to work here forever?”

I: But you didn’t work there forever. Because it turned out ghostwriting was perhaps a little more lucrative than tracking down red-headed Russian spy’s family members.

AC: Ghostwriting became my main source of income, yes. Do you want to grab a drink at another one of my teenage haunts?

I: I love this place. So you came here a lot—

AC: As a young lady. Yes. I think my friend Lisa Crystal Carver got banned for life from here because she got caught having sex in the bathroom.

I: So after working at all the places you mentioned—the babysitting to media job pipeline, as it were—

AC: You joke, but that really was a part of it. I would be watching someone’s kids and then they’d say, “After you’re done here, can you go into the office and transcribe my interview with Mike Tyson?”

I: That’s amazing. So babysitting to assistant editorial work—with a lot of farming in the mix of course—

AC: Of course.

I: To arts coverage, and then to editorial work, to covering crime at the New York Post. How old were you then?

AC: In my mid-thirties.

I: Then what?

AC: Well, I was freelancing to get my own byline out there, writing for Country Living, the New York Times, and a bunch of other places—but I haven’t had a day job in well over ten years.

I: Like you said, ghostwriting becomes your day job. So how do you come to ghostwriting? Are you allowed to say who your first project was with?

AC: Tim Gunn from Project Runway. Gunn and I had the same agent, and he was at a publisher that I’d done work for—Gallery—and they were aware of my work at Nerve and Babble and so forth. So they trusted me and let me take a crack at it. Tim put my name on the cover, which is why I can talk to you about it, and it became a New York Times bestseller.

I: Wow. A success right out of the gate? What was the title?

AC: Gunn’s Golden Rules.

I: Did it feel good that the book was a hit?

AC: Of course.

I: Did you get some of the royalties?

AC: No. Ghostwriting is almost always a flat rate. Almost always. People occasionally get that, but I never have.

But yes, it was great. Tim and I became good friends, and he was really cute with my kid, Oliver, became what we called his Lego patron—

I: How old was Oliver at the time?

AC: Oh, probably five.

I: So you liked ghostwriting?

AC: Absolutely.

I: So much that you made it your full-time job. Now, I know there are many names we can’t discuss, but can you tell us the number of books you’ve ghostwritten?

AC: 28.

I: Jesus. That’s a lot of books! For you, what are the joys—and the pitfalls—of ghostwriting?

AC: I definitely enjoy helping people tell their stories. In a way, I get to be the you in the situation we’re in right now—and I really enjoy that. Also, I really like structuring books. It’s fun for me. I’ve done so many now that it’s simply how my mind works. I look at a manuscript, or listen to someone tell their story, and I start to see things—like in the Matrix.

I: It’s all code to you. It’s all green numbers and letters streaming down the screen. “Bad childhood moment goes here. Triumphant overcoming of adversity in early 20s goes there.”

AC: If I spend a dozen hours interviewing someone—which is usually around 60,000 words—I can often see the whole story. It’s like putting together a jigsaw puzzle. My friend Kathleen says I’m like the girl in the chess show watching games on the ceiling. Which is why I love ghostwriting so much. It’s the person I’m working with’s story—it’s their words—but I know how to take those words and structure them in a way that will be satisfying for a reader.

I: I know you can’t name names, but have you ever had someone you really like, or deeply admire, say to you, “You nailed it.” Someone you were excited to collaborate with who was absolutely thrilled with how the book turned out?

AC: Yes. It feels amazing. That said, most people have a period of trauma first.

I: Because they’re uncomfortable being seen?

AC: It’s really hard for them.

I: Have you gotten that response, too?

AC: Plenty of times. A lot of, “Wait. I said that?” It’s the same as when you hear a recording of your own voice for the first time—the way your voice sounds different in your head versus when you’re hearing it. Or when you see photos of yourself. It’s like that, but on the page.

I: So what do you do at that point?

AC: I sit with them and ask, “What doesn’t sound like you?” Then we work on it until it is more in line with what they were actually trying to say. In a way, this goes back to what interested me about translating Sanskrit.

I: How so?

AC: When translating Sanskrit you have these stories from thousands of years ago, right? You’re attempting to translate those ancient texts into contemporary American English, all while ensuring that they’re still accurate.

Well, with ghostwriting, you’re taking transcripts of interviews with a celebrity and you have to guarantee that they will still sound like themselves—that it’s still their voice—while also turning those transcripts into a book that a reader will enjoy.

In each case, you’re somehow both making a lot of changes, while at the same time trying to make sure the core meaning doesn’t change at all.

I: Have you ever had to battle with someone whose vision of themselves—for example, someone self-lionizing to an incredible degree—put you in a position where you had to bring someone back down to earth?

AC: No. But I’m lucky in that I get to be very selective with which projects I take on. I turn down a lot of books—especially these days.

I: How many projects do you think you’ve turned down?

AC: Oh gosh, a bunch. To be fair, I’ve also interviewed for projects and been turned down, as well.

I: Does it hurt to get turned down when you’re up to work with someone that really interests you?

AC: No. It’s business. It’s my day job. I know I’m good at it. I know I’m really fast. But the chemistry has to be right on both sides. If one book doesn’t work out, something else will come up.

I: That’s part of it too, isn’t it? Speed?

AC: Yes.

I: There’s a saying about haircuts. With enough time, anyone can give you a decent enough haircut—but what you’re paying a barber or hairstylist for is how quickly they can give you a good haircut.

AC: Oh, I never heard that. But yes.

I: What’s your speed? How long does a ghostwriting project take you?

AC: It can be as short as five weeks or so. But you usually get anywhere between three and six months to finish a book.

I: Five weeks? Jesus. I want to hire you.

AC: I’d hire myself, frankly.

I: So it’s different when you’re working on your own stuff?

AC: Of course.

I: Because you’re in your own head. It’s your own words, your own story, and thus it’s harder to structure—at least to structure as quickly as you can structure somebody else’s story.

AC: Exactly.

I: So you’re like a midwife—

AC: A midwife of other people’s stories?

I: Yeah.

AC: That’s right.

I: Were you already ghostwriting before you published St. Marks Is Dead?

AC: Yes.

I: When does that book—your own book—come out?

AC: 2015.

I: You got a lot of love for that book, correct?

AC: I did.

I: You were on the cover of the Village Voice.

AC: Not long before it shut down for the first time, which I try not to take personally—but yes, I was. I really loved that profile. We came here to the Holiday, actually.

I: But people really loved the book—folks in the neighborhood loved the book.

AC: Yes, it felt really good when people connected with that book, because I worked really hard on it. I did more than 200 interviews and tons of archival research—I was in the library all the time—so I was happy when people liked it.

That book, while it was a lot of work, it also taught me how fun a book could be. The tour for that book was an experience. I had this crazy book launch party and so many people from the neighborhood came out. It was at Cooper Union, and—this was Adam Horovitz's idea—

I: Adam Horovitz of the Beastie Boys?

AC: Correct. It was Adam Horovitz's idea to have a book party cover band—a sort of supergroup—that only played songs about Saint Marks Place. So all of these friends and people I knew from all of these different bands showed up and played music, and I gave a talk from the Lincoln lectern. Around 800 people were there. It was really special. The whole tour for that book was phenomenal.

I: Did your dad come to the launch party?

AC: He did. There’s a picture of us.

I: At this point was he at all like, “Hey kid, I thought you wanted to be a farmer. What gives?”

AC: No. I think he was proud of me. Distantly proud.

I: Two years later you publish Wedding Toasts I'll Never Give. How’d that book come to be?

AC: That came from a piece I wrote for the New York Times, “The Wedding Toast I’ll Never Give,” which I wrote in 2016. I wrote the piece in a hotel room. At the time, I was so mad at my then-husband, but I was trying to convince myself to stay with him.

We were going to a lot of weddings, but I was not experiencing the love and promises that so many toasts and vows at those weddings were selling—how magical marriage is. I was really struggling.

I: How long had you and your then-husband been married for at that point?

AC: I think we would’ve been married for eleven years or so.

I: That’s a long time.

AC: We got married kind of young, which means we were going to weddings when we were older and watching a lot of our friends saying things like, “This is going to be so awesome!” Whereas we sorta felt, “Yeah, sure. Awesome.”

But the essay was very loving, and about why, you know, marriage is quote unquote “worth it.” In hindsight, though, it was me trying to talk myself into staying in a marriage that had become difficult in certain ways.

I: Do you regret writing it?

AC: No, I don’t regret writing it. Because it did work, at the time. I stayed. Also, that article became one of the most read Modern Loves of all time, so clearly it helped other people—or gave them something they were looking for—even though my circumstances eventually changed. Plus, it led to my second book.

That said, Wedding Toasts I'll Never Give didn’t, uh, do great.

I: Ruh-roh.

AC: Yeah. The book did not sell well, and my publisher seemed disappointed. I tried to talk about other book ideas, but was told, “We love you, but sales track is sales track.” I thought I would never write another book—another one of my own books—again.”

I: Really?

AC: I thought, “Well, that’s that.” I could keep ghostwriting, but I wouldn’t sell another book under my own name.

I: But that’s not what happens.

AC: No. I keep ghostwriting and freelancing. Then, in 2018, O: The Oprah Magazine approached me about writing a piece about Gen X women, and how… sad we are? And I thought, “I’m sad. I can write that.” Because I was really sad. I thought I’d never sell another book under my own name again. I was pretty broke. So I did some research—it turned out a lot of Gen X women were sad—and wrote the piece.

I: I remember this piece. It was long, right?

AC: 8,000 words.

I: If memory serves—much like your wedding toasts piece for the New York Times—uh, how to put this? A lot of people read it.

AC: It went viral, yes. Like I said, it turned out there were a lot of sad Gen X women.

I: That seems to happen to you a lot.

AC: Being sad?

I: No, you writing a piece that strikes a chord with the culture.

AC: Only those two, really.

I: I mean, those two were monsters. Giant hits. But you’ve gone viral a bunch.

AC: I’d say a few times, I guess?

I: Ok, there are more important things for us to talk about, so I’m not going to fight you. But agree to disagree.

Anyhow, that piece then led to—ta da!—you selling another book. A book written only by you, Why We Can't Sleep.

AC: Yes.

I: Which also got a ton of praise, right?

AC: No. The reviews were… middling. But it sold the best of anything I’d done by that point.

The way it breaks down is St. Marks Is Dead sold decently for what it was, but the reviews were incredible and the tour was like nothing I’d ever experienced before. Wedding Toasts I'll Never Give got pretty good reviews, but poor sales. That said, I made a lot of friends who I treasure through that book—a lot of people reached out to me when it was published. Why We Can't Sleep got some negative reviews, to be honest. At least one reviewer called it “whiny.” But it sold better than anything I’d ever published on my own up until that point.

I: New York Times bestseller?

AC: For three weeks.

I: A commercial success. Apologies for all the shop talk, but this sort of thing fascinates me—and I’m just so, so, so glad you didn’t quit writing.

AC: Me too.

I: Because then you write your latest book, Also a Poet.

AC: I do.

I: So you’re coming off a book which didn’t get great reviews, but did sell really well. How do you choose your next project? How did you know it was gonna be a book about your father and Frank O'Hara?

AC: In 2018 I found these tapes in my parent’s basement while I was looking for something else. I remember thinking, “Hey! What the hell’s all this?” Saying to my father, “There’s like 40 hours of tape here. That’s so much tape, and you never finished the book? How’s that possible?”

I: 40 hours of your father interviewing Frank O’Hara?

AC: No, interviewing his friends. O’Hara died in 1966. This was ten years later, for a biography.

I: But 40 hours. Whereas when you’re ghostwriting a book—

AC: Exactly. I sometimes get 12 hours of tape max for a book I do with a celebrity. So I asked my father if I could have the tapes and his response was, “Sure, whatever.”

So I took the tapes and tried to make a biography out them, but then I ran into all of these roadblocks—

I: With the Frank O’Hara estate?

AC: Yes, among other things.

I: So the original plan was to take the tapes and turn them into a straightforward biography almost in the same way you’d take tapes from a celebrity and ghostwrite a book. You’re thinking, “I’ve spun gold out of less.”

AC: Exactly. I had this feeling toward my father, “How could you have all of this information and not make something out of it?” So I figured I’d do it.

But then I ran into these roadblocks, and also my father got diagnosed with cancer and given six months to live. Then the building my parents lived in burned up in a freak electrical fire. So at that point I was doing a lot of caregiving, and it was a very rough time.

It also brought my relationship with my father front and center, which is when I realized the book was less about Frank O’Hara and more about me and my father. Or, to put it more succinctly, these Frank O’Hara tapes were kind of an excuse to examine my relationship with my father.

My friend Alysia Abbott says this thing about Medusa and the mirrored shield—have I told you this?

I: No.

AC: You may find this useful, too. Alysia says when you’re writing about something, a lot of times you need something to bounce off of. The same way Perseus needed the mirrored shield to battle Medusa—because if he looked directly at her he would turn to stone—so he looked at her reflection in his shield while fighting.

So in the same way, to look at my father—

I: You needed Frank O’Hara.

AC: Alysia’s very smart.

I: What were the roadblocks with the estate?

AC: My father told me he had been denied permission to quote the material and had been denied permission to look at certain letters and archives by the Frank O’Hara’s estate because he had been deemed, to summarize his words, not worthy.

Which made me figure, “Oh. No problem. I’m so nice, compared to my father. They’ll love me. I’m respectful and thoughtful and know how to ask for things in a kind manner. I’m not like my father at all.”

But it turned out they didn't like me any more than they liked him.

I: Is it because they’re waiting for, say, a Walter Isaacson or Ron Chernow type person to write the big, full biography at some point?

AC: I wouldn’t presume to know, but I don’t think so. I think it’s more that the estate believes—and I understand this—the work speaks for itself.

I: Also, Frank O’Hara is so beloved. I can see not wanting to let anyone tinker with that reputation in any way.

I mean, you had that experience yourself. Falling in love with Frank O’Hara’s poetry. So many of us have.

AC: Yeah, my dad introduced me to Frank O’Hara’s poetry when I was eight, which meant a lot to me. Of my father’s whole world, O’Hara’s poetry was one of the only things I could really latch onto. Frank O’Hara always struck me as funny, kind, and interesting. His poetry was wonderful, and I fell in love with it at a very young age. The way that his writing wasn’t esoteric—

I: Which, I’m sure, a lot of your father’s world did feel esoteric.

AC: Exactly. Which is why I carried that collection my father gave to me around everywhere I went. It made me feel special.

I: So, we’ve been talking a lot about your dad, but your ma is the actress Brooke Alderson.

AC: She is.

I: How’d she and your dad meet?

AC: They met at an opening at the Whitney—introduced by mother’s friend, Alfa-Betty Olsen. I think the story goes that Olsen was maybe going to date my dad, but upon meeting him my mother told her, “If you’re going to date him, don’t bring me around anymore.”

I: What a line!

AC: That was sometime around 1973.

I: Do you have feelings about your ma’s career?

AC: I mean, she was in Urban Cowboy. She did a lot of commercials when I was a little girl. She was a character actress.

I: Were you interested in her career as well, when you were growing up?

AC: Of course. She was in an Atari commercial when I was in elementary school. I also remember an Alpo commercial—she had a real run of commercials when I was growing up. She was also on Family Ties and Murder She Wrote. She had a very impressive career.

I: Were those commercials paying the bills? Was your ma the breadwinner?

AC: Oh, absolutely. My mother was the breadwinner. I didn’t think a lot about it at the time, of course—but in retrospect it’s amazing.

I: Was your dad proud of how well Also a Poet did?

AC: I mean, mostly. He loved the book. He thought it was really good—almost to the point where it seemed like he was a little surprised by how good it turned out.

I: In a way that made you feel, “What the fuck?”

AC: A little. But no, he told me, “This is a really good book.” He was also a little surprised, I think, at how much attention it got. That part, I’d say, was harder for him.

He liked the book, but I don’t think he liked how much I promoted the book—or how much attention the book received.

I: Because your dad, for lack of a better word, was a cool kid.

AC: Cool kids don’t do press.

I: But you got through it, because he also really liked the book.

AC: He also really liked the book.

I: Not long after the book’s publication, though, your dad dies, right?

AC: Around four months later.

I: Are you glad that he got to read the book? That it came out before he died? Or would you have preferred—

AC: No. I’m so glad he got to read the book. It was the best thing that could have happened for us. Because he was proud of me, and he was able to express that, which was such an important thing. But more importantly, it gave us an excuse to talk about all of these other things that we’d never talked about.

It was also extremely hard. Not all of these conversations were good news, or wonderful experiences. But they were real. True to life. The hard conversations are important, too. One that I put in the book is, I basically told him, “I think you never thought I was interesting and never really liked me all that much.”

To which he responded, basically, “Yeah. That’s fair.”

I: He wasn’t saying, “No! I was trying to give you space. Allowing you to find yourself!” He simply said, “You’re right.”

AC: Yeah. But it was really good to have those conversations, even the ones that felt horrible. Because then, when he died, I at least felt like there was nothing left unsaid.

The truth is always better. That’s something I believe. Even when the truth is terrible, the truth is always better. You don’t want to live in lies or delusions. It’s always better to know reality.

Because, if you’re honest with yourself, you know the truth anyway. Even if you don’t say it out loud, you know it in your body. So I knew that. I knew my father didn’t think that much about me. Was having him say it aloud—to hear that—was it tough? Of course. But then having it out in the open, there’s something important about that, as well.

I: Why do you think your father wrote?

AC: That’s a good question. My father wrote because he was good at it. He was an extremely talented writer—and he knew it, and he loved having that skill and talent. He genuinely enjoyed flexing that muscle and being praised for it. He really took pleasure in it. I have memories of him coming out of his office and saying, “I'm a good writer.” Or simply, “I'm a writer.” He was so excited to have that rush, to have that feeling. He loved it. I've never had that. That's not why I write.

I: You don’t have that?

AC: No. Do you?

I: Oh, all I want in the world is for somebody to pat me on the head and tell me I wrote something well. Or, you know, that I’m a good boy.

AC: For me it’s really about connecting with other people. I like writing something and having someone connect with it. That’s why I write.

I: Why is the death of a parent so profound?

AC: The death of a parent is very profound, but what’s also difficult is that it’s profound in so many different ways. When my dad died, I thought I’d prepared —because I’d written about him, and we’d had all these long conversations. But it turns out I wasn’t prepared at all. In all honesty, there’s maybe no way to be prepared.

This might sound silly, but “dying” and “death” are so completely different. My father had been dying for three years. But death? When he was actually gone? That was completely different.

I: How did you find out?

AC: I got a call from my mom when I was in therapy. I had missed her call—because I was in my session—but her voicemail said, “I think this might be it.”

Then, when I called her back, she said, “No, maybe it’s ok now. He’s up again, smoking.”

I: He smoked cigarettes until the very end?

AC: Correct.

I: Was it lung cancer that killed him?

AC: Also correct. But I decided to go up and visit, so I could be there with him. On my way I talked to my aunt on the phone and she said, “No, it’s probably pretty close.” Anyway, I got up there and he was dead in three days.

I: But you got to be with him?

AC: “Got to.” You say it like it’s a prize. It wasn’t a prize. It was pretty awful.

I: Hard?

AC: Yeah.

I: The physicality?

AC: Sure, but also, he wouldn’t take hospice, even though he was clearly dying. I kept telling him, “But it would make it so much easier. So we don’t have to bath you”—

I: “So we have some assistance.”

AC: The hospice was provided by insurance. It would help us. But he refused. Until I realized the way to sell him on it—which was to tell him all the good drugs he’d be getting. So I said, “Oh, ok. I guess you don’t want a drug concierge.” To which he responded, “Wait. What?”

I: Smart.

AC: But it’s also true! “You don’t want all these drugs, Dad? I would want all these drugs.”

I: And he said yes?

AC: Yes. Once I started calling it “drug concierge” my father took hospice.

I: You come from all of this—a writer/art critic for a father, and an actress for a mother—and you yourself are a writer. Your son is now almost 18, heading off to college soon. Do you want the artist’s life for him?

AC: My son is amazing. He’s so smart and so sweet. I love him so much. He’s a fantastic photographer, a great actor, and a great writer. He knows more geography and history than anyone else I know, including adults. He’s thoughtful, a considerate friend. He’s also extremely tall and handsome and good company. And he has all these cool hobbies, like he’ll pick a direction and walk fifteen miles, just to see different parts of the city. He is a wildly talented person—he has everything, artistically speaking.

Now, what will he do with all of that? I don’t know. He’s really interested in government, public policy, and city planning. I truly believe he could write novels, or be in movies, if he wanted to. But the truth is, whatever he does is going to be so much more interesting than whatever I can imagine for him.

I: Are you going to miss him when he goes to college?

AC: Yes. I already miss him. We watch Veronica Mars every night, and eat dinner together. I love having him around—I love being with him. I’m going to miss him so much. So what happens next? With him going away? That’s really hard to anticipate. Maybe I’ll do some residencies? Move to Europe? No idea. In the end, I’m simply excited for him to go to college. For him to get out there and be exploring on his own.

I: Final question. Do you ever worry that you being a ghostwriter influences how people see your own work?

AC: How do you mean?

I: To put it another way, you’ve worked extremely hard to get to where you are today. Do you feel like your work as a ghostwriter, or—and to be clear, this may be me projecting my own insecurities—the fact that you wrote viral essays for the internet that turned into book deals. Or even the fact that your father was a well known critic, and your mother was an actress. Any of that, do you worry that people factor that in while judging your writing—your art—as it stands on its own?

AC: Or that my grandfather was Gilmore Schjeldahl, the inventor of the plastic-lined airsickness bag?

I: I had found that in my research, but thought it might be too much to pack in here at the end. But, yes.

AC: I like that my grandfather invented things. I have the art my grandfather had in his factory hanging up in my office—two panels of abstract ‘60s paintings of satellite balloons he invented. I like the idea that the office that I work in is my factory and I am showing up for work each day, even if my work looks different than his did. I loved my grandparents—especially my grandmother—who died just a couple of years ago at the age of 102.

Now, do I worry that people look at all of that and not simply my work? I don’t know. Or, more honestly, I don’t care. Something I’ve always loved is how Dolly Parton answers this question—when people ask her, “Do you mind that people don’t take you seriously?” Or, “Do you worry about all the ‘dumb blonde’ jokes, Dolly?”

Do you know what Dolly Parton said?

I: No.

AC: She said. “I'm not offended by all the dumb blonde jokes, because I know I'm not dumb, and I also know that I'm not blonde.”

So yeah, that’s how I feel about it. I don’t care what other people think about me.

We stop at the Village Works bookshop, and browse the store’s offerings. Ada points out books that she loves, or local writers who are meaningful to her. Outside we pass the St. Marks Hotel. We are close to Ada’s apartment where, in a few weeks, she’ll celebrate her birthday on St. Patrick’s Day. I’ll come over for the party and take a photo of her and her son, Oliver, on their apartment building’s roof as the moon shines behind them. Oliver will have heard from some colleges by then, his next decision—where he goes to school—laid out in front of him.

But for now, Ada walks me up to a large, black cube on Astor Place. I’ve always noticed the large piece of artwork, but never really paid any attention to it.

“It’s Tony Rosenthal’s the Alamo,” Ada says to me. “But most people just call it the Cube.”

It’s still raining and I’m soaked—I have nobody to blame but myself. I shake out my wet hair, as if that might help in some way. Ada closes her umbrella and puts it under her arm.

“It moves, you know,” Ada continues. I didn’t know that. I reach up and touch the sculpture's smooth, black surface.

“It takes two people, though.” I watch as Ada positions herself on one of the other corners of the Cube. “Wanna see?”

She looks at me and I laugh as she says it. But she’s right. I do really want to—I want to use my physicality to change something, anything, even if it is simply this big, black box. People hurry around us, as if they can avoid the rain if they simply move fast enough. Nobody stops to watch, nobody comes over to join us. It’s simply the two of us, our hands on the Cube. Ada’s back to me as she quietly says:

“Ok. Here we go. Push.”

Looking for another way to support me? Consider picking up a paperback copy of Dirtbag, Massachusetts for yourself or a pal. Thank you!

What an absolute banger of conversation. Thanks, as ever, for letting us tag along.

This may be the best one yet—if not, in the top ten. There is nothing missing. Plus it sent me back to Frank O’Hara. Thank you, Isaac, for this walk and for your compelling companion. I think my heart broke a couple of times, which is always a fine thing. ❤️