A Walk to the Brooklyn Heights Promenade with Raven Leilani

"It feels like right now everyone’s a little bit horny, everyone’s a little bit scared."

I meet Raven Leilani for the first time in person on Atlantic Avenue. We are heading to the Brooklyn Heights Promenade, and already the early morning sunlight is nourishing our bodies.

“I come alive in the summer,” Raven says. “I can smell the sun when I wake up.”

An avid walker, Raven moves with ease through the already crowded sidewalks as we pass shopkeepers opening up their stores and construction workers readying their materials for the day. We talk about a plethora of subjects as we move—living for a spell in Washington, D.C., the absurdities of winter, what it was like to study writing under Zadie Smith, working for Postmates, video games, cosplay, fandoms, and how Raven has been craving a slice of pizza—but while she talks she is watching every single person we pass. I observe her as she takes them in, her eyes on a completely different journey than our conversation.

She makes eye contact with a young waitress who is putting out tables and chairs at Table 87, a pizza place. Are they open?

“We open in just a few minutes, at 11.”

Raven smiles. “I could go for some 11am pizza.”

We eat pizza for breakfast as we talk and sit in the sun—behind us a tarp covered in fake butterflies does its best to protect us from the street—and then continue our walk down to the East River.

Isaac: You are very much a capital-W Walker. What do you love about walking and what do you love about walking in New York City?

Raven Leilani: I have an inherent manic energy that I need to express, and New York City is the biggest jungle gym there is. So walking is how I work that energy out. But I also like to watch. And that’s what I’m doing when I go for a big, long walk. I’m watching.

There’s also nothing like the exhaustion after a long walk. I started regularly going for walks around the age of 21. I was working on Varick Street and I lived in Crown Heights. I was single, so I had a lot of time. Had a lot of energy. So I would walk to and from work every day. About 14 miles round trip. And I just fell in love with that trance-like state that comes with walking long distances.

I remember, in those early days, I would make it impossible for myself to get a Metrocard so I would stick with it. And that first week of walking those distances every day was so challenging, but I liked it. I like physical challenges. So those first weeks I’d have to rest in the middle, but eventually walking became a part of me. I love the repetition of it. Repetition feels good. It’s soothing.

I’m that way with music too. I’m always walking with a soundtrack. Or writing with a soundtrack. It’s very rare that I don’t have earbuds in.

I: Music with lyrics? While you’re writing?

RL: Yes. And I know that for some writers listening to music with lyrics makes them feel like they’re working against something, but for me it makes my brain smooth. I can focus and get the words out. And it’s the same for walking. I’ll have one song or five songs that I’m obsessed with—it feels compulsive. Like a circuit. But New York City is made for that kind of circuit. Partly because it’s a pedestrian city. But also because there is a degree of anonymity that you have here, that I really relish. That I’m always sort of seeking when I’m on my walks.

I: Touching on writing, your sentences and use of language are stunning. Is that craft? A gift? Repetition?

RL: It’s really cool that you say repetition because, well, this is the only tattoo I have.

[Editor’s Note: Raven raises her wrist to show the words, “Do not go gentle into that good night,” from the poem by Dylan Thomas.]

This was another one of those moments of falling instantly in love. The villanelle is pure repetition—it’s a circular, musical form—and that was the first kind of writing I ever did and fell in love with. Poetry is very much about that texture and language and imagery and rhythm. So I think that oriented me to write toward what felt exciting—to write to my ears.

It always feels like a kind of half lie to talk about what happens when you sit down and write, because so much of it is something you receive. But I always feel like I know I’m onto something when I have that forward motion with a sentence. Like walking. When there’s a rhythm, a repetition, a density for me to lean into. That’s when it feels urgent, when it feels exciting.

For example, Susan Choi. She blows me away on a sentence level. I’m always looking for that. I need constant fuel—to remind me why it’s stimulating to sit down and write. The kind of books where it’s like, “This is so good I have to start my own thing. I have to work on my own work.” So yes—whether I’m writing or reading—sentences? I think the music is important. The music is always going to be the difference between me liking something and me loving something.

I talked with Kaitlyn Greenidge—whose criticism about Luster was one of the first times the book felt real to me, when it was coming out. I was walking over the Brooklyn Bridge, actually, reading her piece. So I was talking with Kaitlyn very early on in my book tour, and we were talking about echoes—I often have a lot of echoes in my work, and often editors are on the lookout for echoes—and she was talking about the cultural imprints you find in language and writing and she was like, “Well yeah, you’re West Indian, you all repeat yourselves all the time,” and I was like, “Wow, yeah it’s true.” And it’s there. It’s there. That’s also music. It’s rhythm.

Garth Greenwell talks about writing being libidinal and that is 100% true for me. Whenever I’m trying to write about or talk about, “What it is to write,” I’m always talking about guts. I’m always talking about pussy. Those bodily sources.

I: Physical.

RL: Yes.

I: I’m glad you brought up Garth. Because one thing I admire about both your writing and Garth’s writing is how well you both write about sex—not an easy thing to do. Well, let me not assume. Do you find writing sex difficult? Easier? No different?

RL: I love writing sex. I was talking with Adam Dalva recently, and we were talking about the concept of writing deserts and writing oases. Writing deserts are the shit that you’ve got to get through to get to the part that you really want to write. The oasis. For me that’s sex. It’s just so fun. It’s so fun to write.

When I read a book, or watch a movie, one thing I’m always thinking is, “Is there penetration?” I want adult content. Sex is character. Sex is interesting to me. Lisa Taddeo and I did an event last week where we talked about the ickiness—the weirdness—of seeing the evasions on the page around sex. That’s what feels gross to me. The curtain wafting in the wind. The panning away. I want to see all of it. The before part. The routine. What it looks like to ready your body for the act. What it looks like when the clothes are coiled on the floor.

Someone once said to me, “The scariest thing you can do is to say what you want and what you like—to claim the joy rather than claim the disgust.” Although the disgust is also really interesting to me on the page. Sex and pleasure and disgust and the way they are sometimes married. Because when you write towards what is uncomfortable, you are also often writing towards what is tender and what is vulnerable.

I: The book was originally titled A Surplus of Hands.

RL: Wait. How did you know that?

I: Your boy does his research. But sort of playing off of that, and what we’re talking about: How do you know how much sex to put in a book?

RL: In Luster, most of the book is Edie desperately wanting to have sex and not being able to. That is almost more exciting territory for me. The territory of yearning. That kind of derangement is something I’m very excited about. Really into. So for me, in terms of how much sex, it’s not something I know going in. It’s more about finding the organic moments. Where could sex happen? And I follow that.

So for Edie as a character—I tend to gravitate to characters who have that need and that ache. Wherever it makes sense to satisfy that or frustrate that. I’m going to do that. To follow that.

I: Putting out a book any year is going to be difficult, but to put a book out last year seemed almost insurmountable. So to have a book like Luster, that so many people read, and engaged with—how did that feel, during such a tumultuous year?

RL: I think we’re all feral.

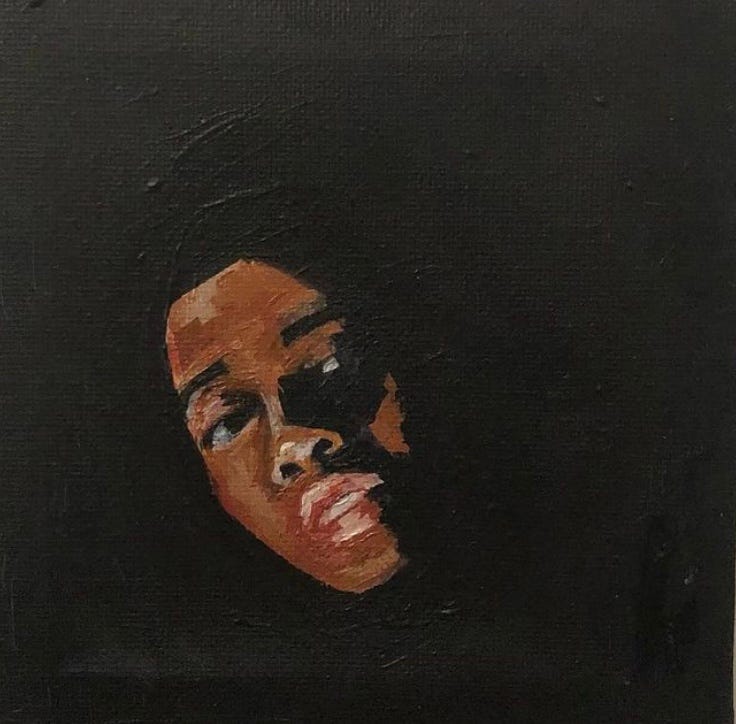

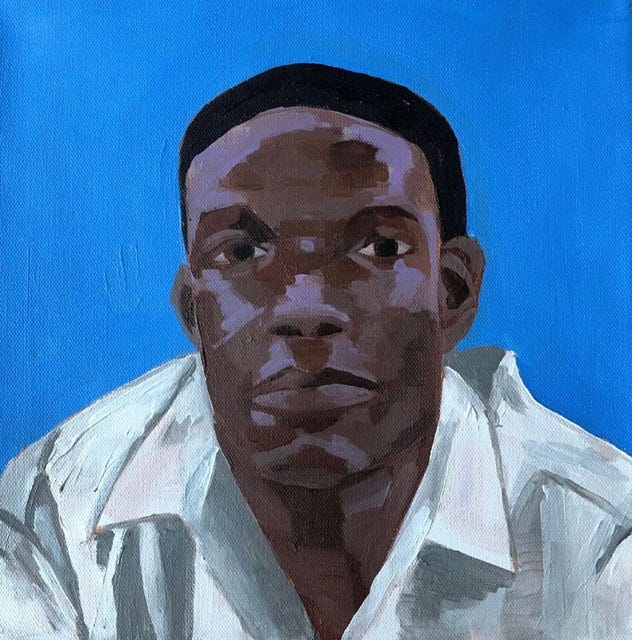

I mean, I don’t want to speak for everyone. Everyone had a different pandemic. But, if you know the original title of my book then I’m going to assume that you know what last year was like for me personally. My dad died in March—in that first wave—he was gone. Almost immediately. Then my brother, Daimion, died. My brother—who had ALS—he was a painter, but he was bedridden and couldn’t really eat anymore. So in a way he was no longer suffering, but both of those deaths sort of happened one right after the other. And that was really tough, because my brother was the reason I started painting. And so, in a way, he’s the reason I’ve written this book. Because he was my entryway into making art.

So last year—for me—the private and public were so separate. When you’re out on the circuit, and this extremely lucky thing is happening to you—you know, you’re trying to figure out who the public version of yourself is going to be. Who is going to stand beside the book? Which was itself such a strange experience. I am very much a perfectionist. I like to feel like I am doing my best. Which is to say I didn’t want to fuck up. I was so scared of fucking up. Out in front of people.

Because that’s another reason why I love to write. I know exactly and precisely what I’m saying. So the idea of doing live events or interviews—for example, technically, a setting like this would usually make me so anxious. So I felt enormous anxiety over not having control over my words. Because I was privately feral and grieving. I felt like all the work I was doing was to manage that—the grief—in order to do justice for this book that I had worked on for so long. And to do justice to the people who helped make this book happen.

So in that way last year was very difficult. I very much had two selves. And I can’t separate it from what was happening that summer, with George Floyd. I was trying—to the best of my ability—to provide neat and tidy answers to these huge, existential, and old, questions, while I was also going through my own grief around the men in my life who were just gone.

To put it another way, it was a mindfuck. And that was true for everyone. Everyone was dealing with this pandemic. “How are you doing?” felt like the most ridiculous question. And no one was saying the real answer. And when you can’t give the real answer you feel isolated. And I think we were all kind of dealing with different versions of that. There is friction there. So really I was packing away what was happening publicly and so I could try and handle what was happening privately.

But now, I can feel it. Now that I’ve been able to grieve. Now I can sort of accept what happened last year in terms of my book coming out and it feels miraculous. Because part of putting art out into the world is being open, and I couldn’t fully do that last year. But now? It finally feels good.

I: So you feel like on the personal level, last year, you were experiencing mourning and grief and it was a compartmentalization to go out and support your book?

RL: Yes.

I: But now you are experiencing the joy and acceptance of the book, almost a year later?

RL: Yes.

I: Another reason for this summer to feel that much better. Because this summer feels like it’s going to be a summer on steroids. Especially in New York.

RL: Totally. I went to The Rosemont with some friends a few weeks ago. It was my first time that I was inside, seeing people dance and be close with one another. And it just felt so good. So good.

It feels like right now everyone’s a little bit horny, everyone’s a little bit scared, and I feel like when those two come together, it’s a primal state. And that’s where change comes from.

I: You’re also a visual artist. What do you enjoy about painting. Does creating visual art feed you differently then writing does?

RL: I definitely have a different relationship to it. I honestly have not painted in a really meaningful way—as in I’m churning out work—in a long, long, long time. I pretty much hung that up when I was around 19. But back then I always had a canvas. I was always up at 2am, rendering a carton of eggs while watching Adult Swim. I loved to work big back then. I had aspirations. My teachers would let me out of class early so I could walk through the hallways with my canvas and not block the other students.

The crew that I was working with at the time, that cohort, so many of them were so, so good. Critique was hugely important. So I think that too, kinda steeled me when it came to writing. I understood what it meant to be critiqued. To be torn apart in a constructive way. So I was always aware that, out of my group, I was not the best artist. That there was always work to be done. So when it was time to apply to college, I looked at my art, my portfolio was together—and the same thing happened when I looked at the book I wrote before Luster—I was like, “it’s just not where it should be. I’m not where I should be.”

For me, more than writing, failure at painting feels so painful. So that’s another way I have a different relationship to painting. Failure feels more painful. It always has. And that scared me a little bit. How mortifying it felt. So I stepped away from it for a bit. Because the act of painting—and trying to get where I wanted to get—was beginning to kind of tarnish the thing that brought me to the canvas in the first place.

But then, very slowly and on my own, I would remember that I could paint something. And I loved it. I took a moment, and I studied a little more. Plus I was older, so there was less ego. I put the effort in, in terms of rendering the ear or the nose. And the more I did it, the more I realized that I could. It just took patience. It took faith. It took enormous faith. And I’m still completely lost up until five strokes before I’m finished. And the fear of failure is still there. But painting for me is that I have to trust that something will eventually come through. And that’s how writing often is for me too, so in that way they’re similar. But painting is still, probably because it’s the earliest failure I can think of—a disappointment in my own skill—it still feels way more naked than writing does to me. I surrender a lot more.

I: Why portraits?

RL: It’s the only thing that interests me. The human face. It’s weird, because I love Edward Hopper. I love a New England landscape or a lighthouse with sharp light on it. High, high whites. And the shadows. But there’s an intensity with faces. With eye contact. That’s what I gravitate towards when I’m in a museum. I want to see a face. It’s the only thing that’s interesting to me.

By now we have reached the promenade. The water is bright blue to match the sky, and the Brooklyn Bridge straddles the East River as we gaze out at downtown Manhattan. We have been talking for hours, but now a calm quiet sets in as we lean against a green railing.

“It’s a show of power,” Raven says, looking at the city. “Brawn. I feel basic for that response and instinct, yet I feel like you can’t help but respond to that enormity. When you’re inside of it, it’s more abstract. But to be able to see the skyline. It is a primal response. The same way a basilica is built to make you feel, as a worshipper, small in relationship to God. It’s magnificent.”

damn damn damn this was good. and Raven's art is incredible!