A Walk to the Double Down Saloon With Karolina Waclawiak

"I really believed I was a piece of shit at the center of the universe."

“You should order the ass juice.”

Karolina Waclawiak and I are at the Double Down Saloon in the East Village. When Waclawiak was getting her MFA at Columbia, she would travel the length of Manhattan to come downtown and drink at the rock and roll tavern. She liked that they played avant-garde porn intercut with footage from punk shows and skateboarding videos on the bar’s televisions, and heavy, thick, guitar-driven metal on the bar’s speakers. I mean to ask her if there’s something about the graffiti-covered Double Down Saloon that reminds her of the bars she hung out in during her early years in Los Angeles—where she still lives now—but I get distracted by the offering of “holiday ass nog.”

It’s early evening, but the sun is almost gone. The short days of winter. There are only a few patrons in the bar. I inquire with the young bartender about the ass nog.

“It’s ass juice, but festive.”

Fair enough. I order a glass for myself and a gin and soda with heavy lime for Karolina. Karolina and I have known each other for years, at times working together. I have long admired her writing—along with her skills as an editor—so was pleased to have spent the afternoon walking with her through the East Village, where she spent much of her teenage years wandering, before she moved west.

Earlier in the day, back before I was sipping ass nog (which, to be fair, is delectable) Karolina and I shared a hearty meal at Momofuku, and then set out for our walk in Lower Manhattan.

Isaac: So where are we?

Karolina Waclawiak: The East Village

I: And where are we walking to?

KW: The Double Down Saloon.

I: Now, I’ve known many different iterations of Karolina over the years. But one of those iterations is Karolina Waclawiak the rocker—a rock and roll gal. Is that fair to say?

KW: Yeah, I think that’s right. It started when I was in elementary school. I was really, really, really into heavy metal. I had an older sister, so I knew about Guns ‘N Roses and bands like that when I was in the fifth grade, which was when I started—to be frank, that’s when I decided I wanted to be a groupie.

I: In the fifth grade?

KW: In the fifth grade. I had just started smoking cigarettes and drinking and I thought I was very cool. Now, to be clear, I didn’t really know what being a groupie meant, or what it entailed. I just studied MTV very carefully and knew I had to get to the Sunset Strip. So, at 18—

I: Wait a second. So eight years later? Almost a decade of holding on to this dream of being a groupie?

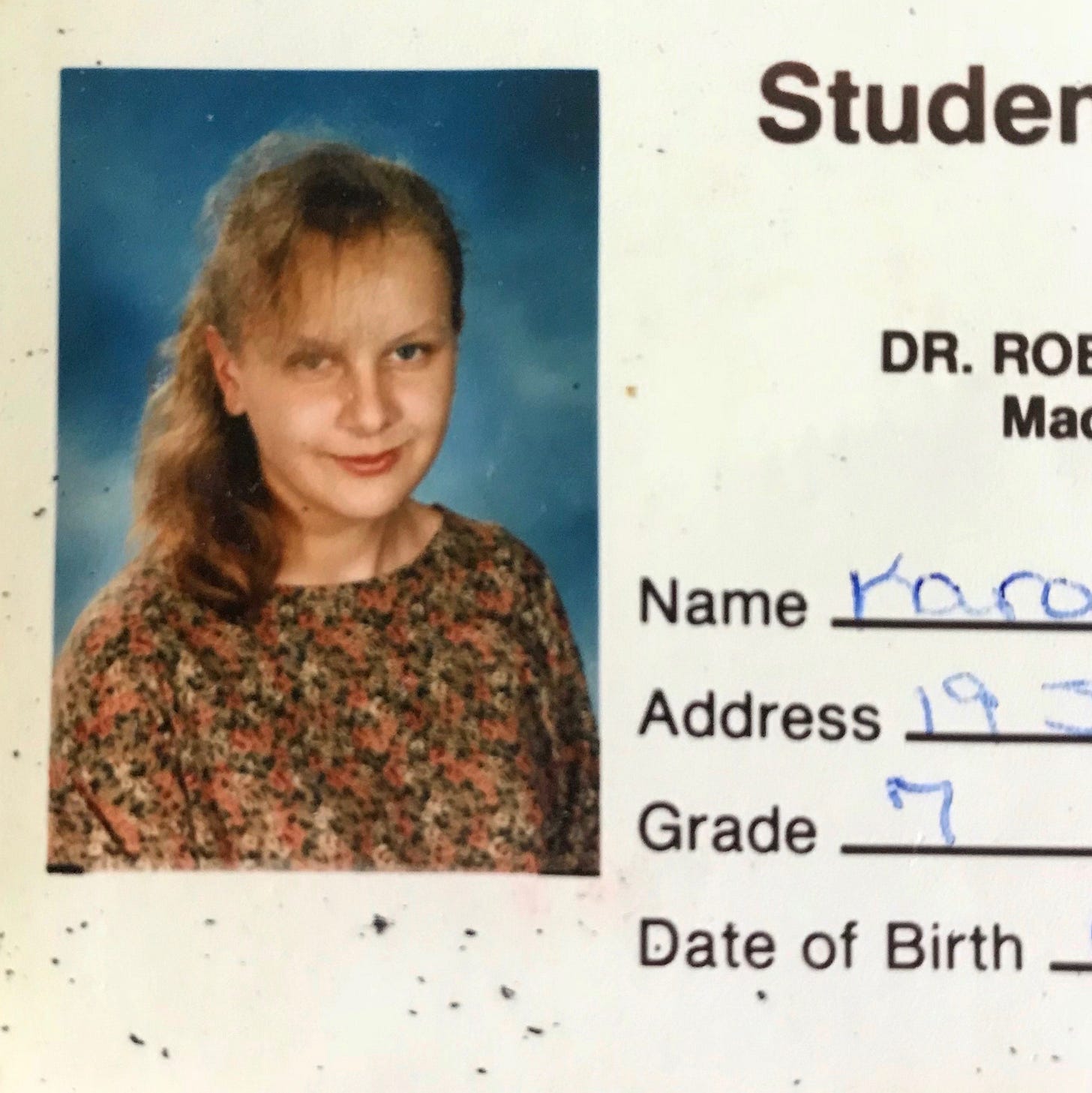

KW: I told my Polish mother, “I want to run away to Los Angeles to be a groupie.” Now, my mother didn’t know what a groupie was either, but nonetheless she was horrified. I got really into it. Big bangs. Lots of makeup. My first concert in the seventh grade was Megadeth.

I: How'd it go?

KW: Oh, I loved it. But it was really embarrassing, because my father picked me and my friend up and there was, of course, all these hot guys with long hair around who I—as a seventh grader—thought I had a chance with.

We didn’t meet my dad where I said we were going to meet him, so he ran up looking for us in a full tennis outfit, with the short shorts and everything. Once he saw us he started yelling at me. I wanted to die. To be fair, my dad loved and introduced me to Black Sabbath so he wasn’t like a square or something. But it was mortifying.

I: So in the fifth grade you decide your dream is to become a groupie. In the seventh grade you’re trying to ditch your father to hang with heshers at a Megadeth concert—

KW: By age 13 I was plotting to get backstage to meet the band. I was friends with a girl who had older brothers with Iron Maiden and Slayer posters on their walls, black lights, and waterbeds.

I: Oh no.

KW: Oh yes. And those older brother’s girlfriends told me the trick to getting backstage, which was giving security guards blow jobs. But I didn't know what that meant. So I simply nodded and took mental notes, but in my mind I truly thought “blow job” meant, well, blowing on a penis. So I remember thinking to myself, “That’s it? Seems weird to blow on a penis, but as long as I get to meet Axl Rose.” I was extremely clueless about sex — as you maybe should be at that age. And on top of that I had a Catholic mother who was dragging me to church all the time to counteract this craziness that I had inside me.

[Editor’s note: At this time we have to take a break from walking because I am doubled over in laughter. Passersby seem concerned for me as I catch my breath at a crosswalk.]

I: At which point you and Axl Rose would—what? Fall in love? Was that the dream?

KW: Kind of. Well, it's interesting because later—much later—I was working for a music manager, Irving Azoff, for a spell. Azoff is huge, and his company repped Scott Weiland—

I: From Stone Temple Pilots?

KW: Right, but we repped Weiland’s new band at the time, Velvet Revolver, which was a supergroup formed with members from Guns N’ Roses. Slash, Duff McKagan, and Matt Sorum were all in Velvet Revolver. So I got to meet all of them, eventually, in my 20s. And I was living down the street from and sometimes hanging out at The Rainbow in Los Angeles.

I: With Lemmy?

KW: I only had the guts to go up to him once.

I: Ok, hang on. We’re getting ahead of ourselves. Before we get out to Los Angeles—tell me about New York City.

KW: I used to take Metro North into the city as a teenager. I moved out to LA when I was 18 and went to film school. But, by the time I actually moved to Los Angeles my dreams of being a metal groupie had died. At that point I had gone through my grunge phase, and then my hardcore straightedge phase. Really, I just loved going to shows.

I: What was it about shows that you loved?

KW: All the angry young men.

[Editor’s note: Another laughing break at a crosswalk.]

KW: Is this entire interview just going to be, “Well, she’s a tramp.”

I: No!

KW: I actually wasn’t at all! Mostly because of all that Catholic guilt and shame that was being thrown at me. My mom knew what worked. But I was a really angry teenager. So, I loved going somewhere—anywhere—where I could feel like I was part of a community of other like-minded, disaffected youth. Which meant that most of my friends were angry, alienated skater boys.

I: You spent a lot of time hanging out in parking lots.

KW: Correct. But I would also take the train into New York City, because I was taking a writing class at Columbia as a teenager. I couldn’t care less about school and had really mediocre and sometimes terrible grades, but it was decided I was gifted at writing.

My parents were super strict, but because I was getting into these high school writing programs at places like Wesleyan and Columbia, they were like, “Well, thank god she’s good at something.”

I: Remind me, what did you parents do for work?

KW: Both of my parents were electrical engineers. Extremely intelligent and extremely practical. They were focused on survival 100% of the time and choosing a creative life path was not the path to financial security to them. It involved too much risk as far as they were concerned.

But, I was accepted into a prestigious writing program at Columbia when I was 16 and then kept going during the school year on Saturdays until I graduated high school. My dad would drive me to the train station at 7am, and my class would be at 10am. Every Saturday was like this. It was the 90s, so this is pre-cellphones, so my dad would just say, “Take the train from Grand Central to be back in New Haven by 10pm.” I had a three hour class at Columbia, but after that? I could do whatever I wanted. There was also a point where I was also taking a zine writing class taught by members of ACT UP at the New School in the afternoons and then a sewing class at FIT because I was obsessed with fashion—I paid for those myself with after school job money. And then I would simply take the subways everywhere and wander around the city. I had an old family camera my dad gave me so I would take a lot of pictures. Sometimes I’d link up with friends and we’d wander around the East Village and the Lower East Side. Sometimes I’d just be wandering alone in the city for hours listening to music on my headphones and taking pictures.

I remember one summer, when I was at the Columbia program, 16 and sitting on the roof of my friend Deborah's sister's apartment. I was looking down at Tompkins Square Park in the middle of the night, and it really felt like I finally belonged somewhere. Like I was a character in the movie Kids. It was that era. Does that make sense?

I: So many kids at that time wanted to belong like that, just not many of us could get to New York City. Teenage Karolina could actually get to New York City.

KW: It seems pretty crazy now when I think about it. I feel very fortunate that I was allowed to go. I mean I wasn’t allowed to hang out in downtown Madison, Connecticut in front of the movie theater with friends and had already been caught smoking and drinking when I was 11. I was arrested in the 9th grade. But I was allowed to have a teenage life in New York City because I think my parents wanted me to understand there was a world outside of the suburban boredom that was getting me in so much trouble. I think they thought it would open my eyes to something more and I wouldn’t be so self-destructive. But I was going to afternoon matinee hardcore shows at CBGBs for god’s sake. I would shop at X-girl because I was obsessed with Kim Gordon and X-Large because I was a Beastie Boys fanatic. I would hang around on Lafayette hoping to befriend Chloë Sevigny— she worked at Liquid Sky, so I would bum around Liquid Sky.

My teachers in the Columbia program would assign me these short stories—stories I’d never be assigned at my suburban, Connecticut high school—Jamaica Kincaid, Edmund White, and Grace Paley. Those stories showed me that there was a whole wide world out there. I remember seeing Jim Carroll and Richard Hell at the Central Park Summerstage, and thinking, “Wait. This can be literature, too?” So I read The Basketball Diaries and Go Now. “Holy shit. Literature isn't just Shakespeare?” Shakespeare being what was assigned to me in Connecticut—and which I hated. In high school I’m getting C minuses in English, but at these writing programs I was encouraged to get out into the world and capture real life. I was being told I was good at capturing it. Then I had to go back to high school every Monday morning and I was like, “Fuck this place already!”

I: When does writing become the dream?

KW: When I was 12. I decided I was going to be a writer when I was 12. It was my singular vision, “That’s it. I know what I’m doing with my life.” When it came time to apply to college, I applied to NYU Journalism school—

I: Undergrad?

KW: Undergrad. I didn’t get in. I was devastated. I couldn’t get out of bed for days. But I did get into the University of Southern California Screenwriting program, which only accepts like 25 people—

I: It’s a crazy hard program to get into.

KW: Right. So I got in there, but I didn’t get into NYU. So I said goodbye to New York and moved to LA.

I: Did you love movies, too? The way you loved the short stories and books that you were reading?

KW: Yeah, I liked weird shit. I saw Cronenberg's Crash—not the 2004 Crash, to be clear—in an empty movie theater when I was at another writing program in Oxford, England and was like, “Oh. This is what I want to do.” Like, “J. G. Ballard is the shit.” But then I go to a school that birthed George Lucas and was teaching students how to make blockbusters—all while I was trying to write the next Welcome to the Dollhouse.

I: Safe to say, the fit wasn’t great?

KW: Not great.

I: Did you have teachers—like at Columbia—did you have teachers who were encouraging you in your weirdness?

KW: Not at first. I got a C+ in my freshman year screenwriting class. The teacher—I won’t name him—told me flat out that he didn’t think the program was for me. I was so embarrassed. I actually almost dropped out of school the first semester of freshman year. I begged my mom not to send me back after Thanksgiving.

I: Jesus.

KW: I didn’t respect that teacher or his body of work, so in the back of my mind I believed he was wrong. But he got to me. I felt I had earned my spot there so I was so confused! I think I said in the first class, “I don’t really know why I’m here” and meanwhile most of the rest of the class had dreamed of being in the movies since they saw E.T. as kids. And I think he clung to that and threw it in my face like I was ungrateful or something. But it messed with me because I thought that being in a writing program like that, I wouldn’t feel like a fuckup anymore. Because all through school in suburban Connecticut I had felt like such a fuckup—I almost got expelled from school in the 5th grade, Isaac. But anyway, other teachers in the program really championed my writing. And the head of the program John Furia, who had written for The Twilight Zone, really got me and encouraged me to stay. Every writing teacher at USC I had was incredible after that first one. I had him again in a directing course and he tried to fail me. An actual F. He was such a dick. The TA, who is now a very successful screenwriter, had to step in and save me. But yeah, my success was never assured.

I: Even in your writing courses?

KW: External writing programs I was great in. Those writing professors encouraged my writing and specifically my darkness. But then you know, I’d get a D- in my senior year creative writing class in high school. I couldn’t get out of my own way sometimes. I knew I was smart, but I didn’t apply myself to things I didn’t care about.

I: Wow.

KW: To be fair, I told my senior year creative writing teacher off in an essay.

I: That might have had something to do with the poor grade.

KW: Listen, I had an attitude problem.

I: Had? Interesting. The past tense is doing a lot of heavy lifting there.

KW: Isaac.

I: What does this part of the city make you think of?

KW: This area makes me feel lucky.

I: How so?

KW: The longer I think about it the luckier I feel. I was so lucky to find other people who were taking their writing seriously—that’s true throughout my life, going all the way back to being a teen at the Columbia writing program. Now, let me be clear, we were writing extremely bad poetry. Yet, that was the first time I found a community of other kids that—they had trouble expressing themselves in productive ways, like I did, but we all discovered we could express ourselves through writing. We quickly became a support network for each other. We hung out with each other outside of class, and we had these teachers—they were all grad students, but we looked up to them so, so much.

One of our teachers invited us to a reading in Hunts Point, in the Bronx. We all go out there together, and at the event our teacher reads poetry about her rape. I was blown away. “Finally,” I thought to myself, “people are treating us like adults. Talking about real things, instead of infantilizing us.” There were a bunch of us—the students—who had really lived through some rough stuff, so to hear her tackle that subject in her work… it was important. We finally had permission to talk about things that were happening to us on the page and to each other.

We were all from different places, mostly in the tri-state area, but we discovered we had so many things in common. At home, in Connecticut, I connected with my friends by going to shows and sharing music—and now I was sharing short stories and going to The Strand. Every time I came into the city I would stop at two places: Tower Records and The Strand. Once I started publishing and my books were at The Strand? It was life-altering.

I: It meant the world to you.

KW: That was it. I had made it. All I had wanted when I was 16 was to have a book that I wrote on those shelves. My dad used to go to The Strand all the time when he had to go into the city for work and he would always bring me home books he thought I’d like. I remember seeing the first book I wrote on a table at The Strand and thinking, “That’s it. I don’t have to do anything else.”

So, I’m feeling lucky. Lucky that I’ve found people who took writing seriously throughout my entire life, starting at a pretty young age.

I: But it ain’t all seeing your book at The Strand, right? Going back to LA, you didn’t exactly love your screenwriting program. You—how to put it? You don’t gel with the academic setting. Did you graduate?

KW: I graduated. But it was wild. I was in one of the most competitive—if not the most competitive—film program in the world. We were writing scripts, sure, but also making short films. We had to cast them, direct them, shoot them, edit them, score them—everything—and then present our films in class for critique. But, I didn't want to cast actors, so I started making stop-motion animation films because I was really into the Brothers Quay and Jan Švankmajer.

At that time I was also volunteering at a needle exchange in Hollywood, so I did a documentary about the street kids at the needle exchange. How they ended up in LA, how they ended up on the street, what their lives were like as teen sex workers. Then I made another one about a needle exchange on Skid Row. On 6th and Gladys, I think it was. And these old timers who had seen everything on the streets and were still alive and vibrant and amazing. And the director of the needle exchange screened the short films for doctors at USC hospital in East LA so they could have more empathy for the people who were seeking care in their ER off the street. I felt really proud of that. I felt like, ok this is why I came to film school. To communicate the truth about people’s lives.

So I didn’t feel like I was particularly fitting in with the USC community but I was super ambitious. So, as in high school, I looked outside the classroom. I became an intern at a management company. I did anything I could that might help me “make it.”

I: You felt like you had a shot.

KW: USC made you feel like there were 100 agents waiting for your script upon graduation—and, to be fair, I did get a manager right out of college. But it was such a fucked up experience. I needed to get my ass handed to me to get the chip off my shoulder. Because I was convinced I was going to make it at 22 years old. Which is preposterous—and it didn’t help that I’d already been delusional since I was, let’s say, 12. But honestly, I just felt like I had to make it ASAP to prove to my parents and maybe everyone that I wasn’t a complete fuck up.

I: You were driven.

KW: I was emailing the heads of production companies saying, “You should read my script,” like a crazy person. Simply getting my hands on their email addresses and sending them my scripts, cold.

I: Like I said, driven. No fear.

KW: Or delusional. But I knew in my heart—I felt it so strongly—that I was going to make it. That it was only a matter of time. I felt like I had to prove it to myself.

I: I mean, not to bring up your parents, but it’s a very immigrant outlook.

KW: Yes. I had no connections. I knew no one in LA. I knew no one in the industry. But I figured if I simply worked harder than everybody else, I would make it.

I remember when I was going to USC, my parents were like, “You have no connections. How do you think you're going to break into this business?” And I said, “Don’t worry. I’ll figure it out.”

I: “I’m going to make those connections myself.” So what does that look like in reality?

KW: I mean, I eventually did end up working as an assistant for The Simpsons. In my mind, I had reached Mount Olympus. Being in table reads for Simpsons episodes was next level. I felt lucky to be cleaning the garbage out of the writers room after everyone had gone home.

I: Hey! That’s not bad.

KW: Yeah. But then the 2007 writers’ strike happens.

I: Would you have preferred to go to school in New York? When you were applying to colleges was New York better than LA in your mind?

KW: Yes.

I: Had you ever been to Los Angeles before?

KW: No. I had never been to LA before. But I visited the USC campus after I got accepted, and there was no question that I was going to go there because of the prestige of the program.

But my dad said, “You better figure out a way to apply these writing talents in a way that will get you paid.” He wasn’t going to help me go to college to study poetry, you know? Again, like you said, real immigrant shit. But that was part of it too, for sure. Hollywood at least seemed more lucrative than focusing on the emo poetry I was still writing.

There’s this weird saying I have, which I think applies here. Or at least applied to my Hollywood ambitions in my early 20s: I really believed I was a piece of shit at the center of the universe.

I: A philosophical mix of self-loathing and importance.

KW: I had this belief in myself that also came with self-loathing. Exactly.

I know I was put on this earth to do this—but I also heard capital-N, capital-O, “NO” so, so much. So my philosophy, to use your word, out in LA was, “I’m going to be the last man standing. I’m simply going to stick it out.” I watched people quit school, or immediately stop writing after school, and I said to myself, “All I have to do is keep writing.”

After college I was dating someone in law school. So every Saturday we would go to the downtown public library, sit in the same seats, and he would study for law school while I would write scripts. Cut to me at the LA Times Book Festival years and years later—there was a gala at the Los Angeles Public Library, and I snuck away from the party to go look at that lil’ table that we used to work at.

I: Awwwwww. It works out! Ok, so you make it through school by—to put it bluntly—fighting like hell. Last man standing philosophy. But, I gotta get to this while we’re talking LA. How does Lemmy and your time at the Rainbow fit in here?

KW: Oh, that’s easy. I was a hard worker. But I was also a maniac. So I broke up with the law school person—

I: What? What happened? The lil’ table at the library, Karolina!

KW: I broke up with him after he took the bar. I went home for a while then, back to the east coast. To collect myself. Then I came back to LA.

I didn't really know what the fuck I was doing at that point, because I was barely writing. I had even gone through all the city tests to be a 911 operator and thought I would just work for the city of LA forever or something. I had totally lost confidence in myself. All the “no”s I was hearing were really starting to build up.

I: What were you doing for work?

KW: I always worked odd jobs. Mostly retail. Beauty shop. Clothing store. Low wage hourly jobs. That kind of stuff. So right after college, I ended up being the manager of a high end vintage and design furniture store. When I came back to LA after my breakup I went back to the furniture store for a while even though I promised myself I wouldn’t. I had to pay rent. Listen, here is a great example of what a crazy person I was. The storeI worked for had celebrity clients, so I had to email them about their $30,000 Italian sofas. So I would write them as a representative of the furniture store, and then later I would write an email from my personal account saying, “Do you want to read my script?”

I: Oh no!

KW: I was that person. But how else was I going to make it?!

I: That's amazing.

KW: I did it to Jennifer Aniston. No shame. I remember thinking to myself, “Maybe. You never know.”

I always really respected the person I would write to—because I wanted to work with them, right? But they would always write back, “How did you get my email?” To which I’d respond, “I don’t know.”

I: I'm sure the furniture store appreciated you not saying, “I stole your email from the place where you bought that expensive bed you love so much.”

KW: Well, they didn’t appreciate how much I wrote while I was on the clock, I can tell you that. After that job I worked secretary or assistant jobs, temp jobs, where I would also write. Every job I had, I tried to write as much as possible. I had two goals: Get a paycheck and have time to write.

But this is the closest I came to giving up. I was 26, nothing was working out. I came so close to applying to nursing school and giving up on writing entirely.

I: Again, a very tried and true Polish immigrant path.

KW: 100%. I was considering it because my dad kept saying, “Go be a nurse. Enough of this. Go be a nurse. It’s not working. Figure something else out. You would be a great nurse.”

I was about to apply, but first I said, “Let me try to make it in LA one more time.” So I moved in with this woman, who I had only met a couple of times before—we ended up becoming best friends. But I quickly became, there’s no other way to put it, I partied a lot.

I: This is where Lemmy comes in.

KW: Yes. I got the aforementioned job working for Irving Azoff, which was an assistant job, but an assistant job with perks. So I would have these assistant jobs that comped me courtside Clippers tickets when my boss didn’t want to go or better seats at Dodgers Stadium than Larry King had. But I was only making $34,000 or $40,0000 a year answering phones and scheduling executive lunches. In that era, it was the Cobrasnake era, I spent a lot of time hanging out in Hollywood clubs with Hollywood club girls. It was really fun to be honest.

Then I got the job at The Simpsons. I remember the first time I walked into the writers room at The Simpsons like it was yesterday—because I had grown up on The Simpsons. I was obsessed with The Simpsons. I even had a poster of Bart Simpson on my wall when I was a kid.

I: Bart Simpson and Axl Rose.

KW: Like I said, anyone who was bad.

But I remember walking into the writers room and thinking to myself, “This is it. I made it,” but also, “How did I get here? I’m an immigrant kid with immigrant parents. I didn’t go to Harvard”—

I: You were born in Poland, right?

KW: Yes. I was born in Poland and then my parents escaped communist Poland—and now I’m standing in the writers room of The Simpsons. It was a God shot moment. It felt like a sign to me. There’s some higher power at work here, and I’m going to get where I’m going, so long as I’m patient.

It was an incredible experience. Sitting in on table reads, and listening to the voice actors do their thing. Watching writers react when their jokes hit—or watching what happened when their jokes didn’t hit and they rewrote the joke in the room. I learned so much. But I wasn’t writing.

I: What was your job?

KW: I was the assistant to one of the producers, Richard Sakai. My name is only on 25 or so episodes, “Assistant to the producers.”

I: Only 25 episodes? Karolina, that’s amazing. In the credits, you mean?

KW: Yeah.

I: When is this?

KW: Around 2007.

I: So what happens during the writers’ strike?

KW: That’s the thing. Then it all stopped. We were twiddling our thumbs. Well, I was twiddling my thumbs and partying. Being afraid I was going to get laid off at any moment after finally getting the dream job. Running up my credit cards, going out every night, all while not writing at all. I wasn’t writing before the strike either, I was being an assistant. But it was around that strike that I realized, “I’m going to die if I don’t start writing again. I have to leave Los Angeles. I have to stop partying.” But I was also mostly hanging out with people who went to CalArts. So I was into art and music and film, too. Not just like, taking Percocet and passing out.

But right before I left, that’s when I was partying the most. One guy I was dating off and on came out from the east coast and we went to the Rainbow and Billy Idol had just left but we talked with Lemmy—there’s a photo of me kissing Lemmy on the cheek that night—and then we went to the Cat Club and Jimmy Fallon was there, funnily enough singing the hell out of a bunch of Motörhead songs. My ex and I are still friends, and he still talks about that night as one of the best nights out he’s ever had.

Another friend visited me once—one of my childhood friends who was as obsessed with Guns N’ Roses as I was when we were growing up—and I got to introduce her to Duff and Slash, which was really special. I was an assistant and I knew the other assistants and we would help each other out, and let each other know where the party was, things like that.

I: A bit of an operator.

KW: An operator, sure. But I wasn’t writing, and I was really partying. I began to realize that the longer I stayed in Los Angeles the more likely it was that I was going to become a drug addict. That the partying could go from fun to—something dangerous.

I: Off the deep end.

KW: Yes. So, I applied to school. I applied to one school. Columbia.

I: New York City, which you of course have fond memories of, especially in terms of writing when you were a teenager.

KW: Correct. It gets me back to New York.

I: How old are you at this point?

KW: 27. So I get into Columbia, which is great. But of course, right as that happens, the writers’ strike comes to an end.

I: Oh no! Decision time.

KW: I remember asking my boss, Richard Sakai, “What should I do?” And to his credit he said, “This assistant job will always exist. People will always need assistants. If you want to be a writer, go be a writer.” I mean he had nurtured Wes Anderson, Luke Wilson, and Owen Wilson’s early careers. He had let them stay in his house when they had no money!

So I listened to him—I left and went to New York.

I: Hooray!

KW: Well, not exactly. Because I’m starting over, in a way. Again. I know absolutely nothing going into grad school. Everybody is reading Ben Marcus and I’ve spent my 20s reading Charles Bukowski and John Fante.

Once again, I was really out of my depth. A party person who, at best, was trying to slow down the party—and all of a sudden I’m surrounded by all of these literary people. It was a real education. And I felt dumb for a long time.

I: You did? You weren’t thinking, “Fuck these soft, overeducated nerds?”

KW: No! I was immediately thinking, “I’m an idiot. I don’t belong here.”

I: But hang on, because this begins to look like a pattern now. You felt this same way at film school in undergrad—

KW: In a way, the same thing sorta happens again. I keep trying to write about lived experiences, and some people around me are really into being the next David Foster Wallace. Which isn’t a knock, I simply hadn’t read Infinite Jest. So I went to Columbia with a real learning curve—

I: Who were your classmates?

KW: Oh, the talent was wild. Jessamine Chan. Diane Cook. Catherine Lacey. There were 35 students, or maybe 40 tops in each year at that time. It felt like a real incubator of talent. That’s where I met Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah, she was in the nonfiction program there.

Plus the professors were great. I studied with Sam Lipsyte, which was really life-changing for me—because Sam writes stories about overlooked people, the same kind of stories I wanted to tell. I studied with Christine Schutt, who really made me fall in love with the sentence. Gary Shteyngart was my thesis advisor, Donald Antrim was there. Everyone at Columbia—both the students and the professors—were just an incredibly talented bunch of people who were really generous with their time.

Now, it was also crazy expensive. As was USC for undergrad. I couldn’t afford either school I went to. But my mom was of the mentality, “Go to these schools to be around rich people and it will open doors for you.”

I: Again, a very immigrant mentality. Was she right?

KW: She was. Now, I’m not going to tell you what student loans I have, but her theory was sound. My mom was obsessed with access, and she was right.

My parents instilled that in me. Even at Columbia, I was still thinking, “How am I going to make money? Nobody is going to give me money.” So, when I was in LA, it became very clear to me that spec scripts weren’t selling, but adaptations of books were selling—adaptations of books and Marvel movies, which had just started selling. I knew I wasn’t going to write a superhero movie, but I figured, “I can go write a book and then I can sell that book to Hollywood. That’s how I’ll make some money.”

I: Wow. So, yet again, your answer is, “I simply have to work harder.”

KW: Go in through the side door.

I: Not so much with the, “Work smarter, not harder” mentality.

KW: Oh no, not at all. I’m just going to work really, really hard.

I: So what do you do at Columbia?

KW: At first I wrote some short stories—and one of those stories eventually became the basis for my second novel The Invaders. But the main thing I accomplish at Columbia is my thesis, which Christine, Sam, and Gary very much helped me with. My thesis becomes my first novel, How To Get Into the Twin Palms.

Again, the process was very similar—a few important people that I really respected encouraged me, and that crumb was all I needed.

I: Another pattern emerges.

KW: I took the book out and queried agents and, again, all rejections.

I: So you finished your first book while you were at Columbia?

KW: Absolutely. When I arrived on campus I told myself, “I’m leaving here with a finished book.” Which is what I did.

I didn’t pay that tuition, and go into that much debt, to not leave with a book.

I: At what point do you start working at The Believer? Do you work there during grad school?

KW: God damn it, Isaac.

I: What?

KW: Nothing, just—this is yet again me being an absolute loon.

During the first few weeks of grad school they have all of these intro meetings with the professors, where they tell us about opportunities for internships—and everyone wants an internship at the New Yorker. But the internships at the New Yorker are only for six months or something, and then you’re out of there. So I decided to aim for a smaller place, somewhere that might let me stick around, or maybe even move up the masthead.

So Heidi Julavits and Ed Park are professors at Columbia.

I: Editors at The Believer.

KW: Yes. So I start emailing them—

I: Another pattern!

KW: I keep emailing them, “I would like to be your intern. I would like to be your intern.” No response. So then I look up Ed Park’s class schedule—

I: Karolina!

KW: What?!

I: How do you even know what The Believer is at this point?

KW: Funny you should ask. Richard Sakai—

I: The Simpsons producer? Your old boss?

KW: Correct. Richard had all of these issues of The Believer in his office, and he told me, “These are collector’s items. Don’t touch them.” So I would read them when he left the office, and I remember being really impressed.

I: Thinking, kind of, “This is the cool kids magazine.”

KW: So when I found out Heidi and Ed were teaching at Columbia, and I thought to myself, “That’s where I want to work.”

I: So you started stalking Ed Park—

KW: I looked up Ed Park’s class schedule—he remembers this, too, because we talked about it somewhat recently. Anyway, I waited outside of his classroom, and he went to go to the bathroom. So I waited outside of the bathroom—

I: Karolina!

KW: When he got out of the bathroom I accosted him, saying, “I want to be your intern. Did you get my emails? I emailed you about wanting to be your intern.” He was so taken aback, but he finally said, “We don’t really have interns.”

I: To which you responded?

KW: “I don’t care, I’ll do anything.”

So Ed relented and said, “Let me talk to Heidi.” After that they interviewed me—and I remember thinking, “These two people are so much smarter than me. Even if they do let me work at the magazine, how will I even do this?” All the while, they were saying, “We’ve never had an intern before. We have no money.”

I: But you got the job.

KW: I mean, yes. They let me read the slush pile. But that led to another one of those, “I did it,” moments.

I: When you became an intern?

KW: When they made me an assistant editor, and started paying me $75 dollars an issue. I couldn’t believe it. I was actually working for a magazine.

I: So that was Columbia.

KW: That was Columbia. I read, I studied, I wrote, and I obsessively read The Believer slush pile. Eventually they made me deputy editor. Still getting a tiny stipend.

I: Sweet. Do you remember any standouts from the slush pile?

KW: Leslie Jamison’s “The Immortal Horizon”—the essay about mud-running—was in our slush pile. We published that, and then her essay “The Empathy Exams.” I was really proud of that. I found a lot of brilliant writers in the slush pile.

Eventually Heidi and Ed trusted me to start editing pieces, so I was working with writers I was a huge fan of. Heidi and Ed’s trust meant so much to me. I would do a first pass, and then Heidi and Ed would really rip it up. I learned so much from watching them edit—and editing other people’s work really helped improve my own writing.

I: How long were you at The Believer?

KW: Eight years. I ended up at the top of the masthead.

I: Like you were hoping.

KW: At the end, for a few issues, it was Heidi, myself, and Vendela Vida as the top editors.

I: So this is through grad school and then after grad school. Were you always in New York?

KW: Well, eventually I moved back to LA. So I was working on The Believer, but was paying my bills working as a secretary at a law firm. But I kept those two lives very separate. I published How To Get Into the Twin Palms and eventually The Invaders, but I remember keeping it all very secret from most of my bosses at the law firm. I was worried I’d be fired for not being serious enough about being an assistant.

I never expected to make a living just from writing. Maybe editing, maybe selling a script or having a book optioned. But all the writers I admired? They all had day jobs. Or they all came into success much later in their lives. So I had my writing life, and I had my working life.This was a real white glove law office. The place represented Steven Spielberg, Clint Eastwood, and Stephen King. Eventually, my boss—who was a paralegal—found out I was a writer and was really excited about it. She was cool. But yeah, I was once again in LA, surrounded by some of the most powerful people in the world, with no power of my own at all.

I: So, did you have an agent at this point?

KW: I didn’t have an agent when I sold my first book—which, unsurprisingly, gave me this whole, “I don’t need you assholes,” attitude. Which I’m happy to say I got over, and I ended up working with Kirby Kim, pretty much immediately after I sold my book. I love Kirby so much.

I: So you’re working at a law firm in LA, but you’re editing The Believer. You mentioned Leslie Jamison already, but what other writers did you love working with while you were there?

KW: Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah’s piece about Dave Chappelle is, of course, extremely special to me. I remember her calling me—she was trying to track him down. She eventually even went to Yellow Springs, Ohio without him agreeing to anything or even responding to her interview requests just to try and see if she could get to him. I remember Rachel calling me and asking, “What are are going to do if he doesn’t talk?” And we decided we could write around him. Enough people—other people—would talk about him, that we could build it from there. Plus, he’d heard through the grapevine that Rachel was interviewing people about him, so maybe eventually he would actually talk.

When Rachel was in Yellow Springs I remember she called me and said, “I saw him. I’m in a coffeeshop and I saw him. But he won’t talk.”

I: Wow.

KW: She said he had walked in, saw her, and then left. But Rachel went on to write this incredible, incredible profile of him—without him. It was so good. No one got him like she got him. Even without the interview. And then we worked on it together, and then it was nominated for a National Magazine award. So that one was really special.

That was the first time I really allowed myself to think, “Oh, maybe I am sort of good at this. Maybe I’m not a piece of shit.” Not long after, a bunch of essays I worked on where in Best American, or writers would email me or call me and say, “That essay we worked on together got me a book deal.” That’s when I really fell in love with editing. I loved the feeling of helping people—and especially helping people figure out this world that had been such a struggle for me.

I: What were you making at the law firm?

KW: $65,000. The most money I’d ever made in my life, easily. But in the back of my head, I was thinking, “Man. I thought I was going to be successful.” I was happy with my editing work, and it was fulfilling, but it sure was looking like I’d be working at the law firm for the rest of my life.

I: Is that when you get the job at BuzzFeed News?

KW: Yes. A few magazines in New York had reached out about editing jobs, based on the pieces I’d edited and published at The Believer. But there was no way I was going back.

I remember, when I was still living in NY before I left, waking up on my 33rd birthday and feeling total doom. I had already published a critically acclaimed book! But every credit card I had was maxed out. I couldn’t afford rent. Bill collectors were calling me. I was behind on my student loans. I remember wanting to walk in front of a bus—I just couldn’t do it anymore. So even when job offers appeared, I promised myself I wouldn’t go back to New York. I was traumatized by how broke I had been there. And I was actually managing to crawl out of some of that debt in LA.

I: But with BuzzFeed News, you could work in LA.

KW: Correct.

I: How long after your “throw myself in front of a bus” 33rd birthday did you start working there?

KW: I was 36 when I started working at BuzzFeed.

I: And how long were you there?

KW: Eight years, give or take. A long time in media, to be at one place.

I: So you start as the deputy culture editor at BuzzFeed News, working with Executive Culture Editor Saeed Jones. Then he moves on and you become Culture Editor, and eventually the Editor in Chief of BuzzFeed News, right? No longer in need of a secret job, I hope.

KW: No. Finally I could have one job and not 4-5 cobbled together to make a living. It was a singular experience that can never be recaptured in another media job. But it had similarities to my time at The Believer, just with a lot more money. I loved helping people make their work better. Improve their writing, report out their stories, turn their wild ideas into pieces that hit a nerve and had millions of people reading their work. I loved encouraging writers to take big swings. To take risks! I really enjoy helping people. We had carte blanche to do things no other place would ever in a million years let us—certainly not me—do.

I: Build their careers? Would that be a good way to put it?

KW: Yes. At BuzzFeed I also produced—and as a consultant continue to produce—documentaries based off of reporting through BuzzFeed Studios. So I was also trying to get those stories out in an even bigger way.

I: Given your time at BuzzFeed and—how best to put it—the current media landscape, any thoughts on what's next for the industry as digital media seems to crumble?

KW: There are so many talented journalists—with incredible stories. Sadly, there are fewer and fewer outlets at which to tell those stories. For me, that's really hard, because I built my career on helping talented writers get their work out there—and what’s happening now just feels really, really bleak and really, really sad. Especially because it means that there are more voices—young, vibrant, smart, diverse, culture-shifting voices—that are going to be left out of the conversation.

Now, I do believe other media outlets and other publications will rise up—will fill the void of this moment, you know? I love what Defector and 404 are doing—they’re producing incredible journalism. But for the rest of media— I’m wary of writers and journalists simply operating at the pleasure of billionaires. I mean, I guess at this point we’re all alive at the pleasure of billionaires.

I: Let’s talk more about your own career outside of editing for a moment, though. Because you do help other people build their careers, but you’re also an extremely talented writer yourself. Your latest book, Life Events—I loved it. One thing the book gave me—I’ve lost so many people over the years, and as I get older more and more people in my life are dying. We don’t talk about death well, as a society. Even now, I’m having a hard time articulating what I’m trying to say. I guess I could start with, thank you for writing such a good, straightforward book about death.

KW: I was talking to someone about this recently—about being death obsessed.

It feels like I've been death obsessed my whole life. When I was a little kid, in the summers, I would get dropped off at this pool. But the pool was next to a cemetery, and while my sister swam, I used to sneak away to go hang out in the cemetery. More than once, there would be a burial taking place, and I would try and hide behind a tree or a bush or a tombstone so I could watch it. Or I would simply wander around, looking at headstones and reading the people’s name and asking myself, “Who were these people? What were their lives like?”

I: Did anything happen—when you were young—to spark this interest?

KW: I would say I was death obsessed because my mom got sick with cancer when I was 12. And from then on I was waiting for the other shoe to drop through the remissions and returns.

I: Waiting for her to die?

KW: I know how it sounds, but yes. I sort of grew up waiting for my mother to die. So, I don’t know. Death interests me. And I think there’s no honesty about death in America. We hide sick people away. We hide death away.

In a way, I think the pandemic forced many of us—or society—to look at death in a straightforward manner for the first time. I don't think people have experienced mass death across the globe, in such an acute way before. I mean, at the time I was working in a newsroom. I watched people tracking those deaths in real time, and I watched the fatigue happen in real time. People just didn't want to face—couldn’t face—what was happening. People started to simply ignore it, because they didn’t know how to process what was happening. And it was as if that was the first time some people had even considered death. Which seems crazy because we’ve long lived in a culture of mass death—with mass shootings, wars we fund, etc. Some people just tune it out.

But I really believe we need a culture shift in America when it comes to talking about—and accepting—death. Which is also a way of saying that we need a culture shift around aging. America is obsessed with trying to reverse aging. I am constantly fascinated by all of these billionaires who are pouring money into trying to live forever. Their hubris is so interesting to me. Accept facts, you’re mortal too. You don’t get to cheat death.

There's a tech visionary Ray Kurzweil, who wrote a book about the singularity. I watched a documentary about him—and I wasn’t so much interested in the singularity as I was by what motivated him to focus on this one particular topic with such intensity.

To me, it seems so clear to me that he is focused on life extension and solving the “problem” of death because he couldn’t handle the grief of his father dying. Or, maybe a better way to put it would be that he didn’t know what to do with his grief, so he became obsessed with solving this issue to alleviate pain.

I mean, I don’t know. We're all gonna die. Everyone you love is going to die. You will likely have to watch them die. I think these are painful and uncomfortable truths to grasp. Life Events is all about how people try to avoid the pain of loss. But we need to figure out better ways to talk about it, and to face the inevitable.

I: Beautifully said. Now let me do exactly what you’re talking about, and not face death by changing the subject.

Something I’ve always loved about you—and, at certain times throughout us knowing each other, something I’ve been intimidated by—are your hand tattoos. Not just on your fingers, but tattoos on the palms of your hands. Can you tell me about them?

KW: I had a period where I was really captivated by white ink tattoos. So I tattooed my knuckles in 2007—

I: Sort of the final days—back when tattooing your knuckles could be considered an actual job-stopper.

KW: I got a diamond in white ink, and then I kept getting hand tattoos in white ink. I have a bunch of white ink tattoos on me. Then I finally decided to tattoo my palms with black ink, which was really physically painful because you have to do it a few times on the palms for it to stay.

I’ve had them for a long time now. Sometimes I love the way my tattoos look, and other days I think, “What the fuck is this? Why’d I do this?”

It’s funny that you use the phrase “job-stopper.” Because I remember thinking that at the time—not so much that my hand tattoos would be job-killers, but more, “I hope whatever job I get is cool enough that these aren’t a problem. That I won’t be judged for them.”

I: That’s a great way to put it. Ok, another thing you love, along with death and hand tattoos—apologies, that’s a rocky transition. But you love the desert. I’m an ocean man, myself. So tell me, why do you love the desert?

KW: I love the desert. I remember living in New York and feeling, “I don’t see the sky enough. I need to see the sky.”

We immigrated from Poland to Texas. And so when I was a kid my family would take road-trips. We couldn’t afford to fly, obviously. Driving through West Texas when I was five years old—those trips had a real hold on me. I have vivid memories of staring out the car window, completely lost in the big, endless sky of West Texas.

I’ve never really felt at home anywhere, so I think I’ve been drawn to these early childhood memories I have of vast expanses. Which is why I got out to Joshua Tree so often.

I: The big, endless sky feels like home to you.

KW: A big sky and a long horizon line is very comforting to me. To see that much sky, it reminds me that I’m just here for a moment. That we’re all just here for a moment. Nothing Is permanent.

I: Not even the sky.

KW: All of this land will be here longer than us. These things that I think are insurmountable, or soul-crushing—the problems in my life. Well, they’re actually pretty meaningless. The desert was here before me and the desert will be here after I’m gone. We’re all pretty meaningless, in the grand scheme of things, and I don’t know about you, but I find that to be very comforting. I like that we’re impermanent. I like that nothing lasts forever. My problems are so insignificant.

Things that scare me? That I think have power over me? I mean, in the end, who fucking cares? Because I have faith that what is meant for me will not—and cannot—pass me by.

By now the sun is long gone, and I’ve had my fill of ass nog. The Double Down Saloon is starting to fill up with young drinkers setting out on the start of their Saturday night adventures, along with older, rock and roll-worn regulars.

Still, Karolina and I continue to talk as the bar around us becomes rowdier. We discuss her fourth book, which she recently finished, along with her future plans for Hollywood. We talk about astrology and the tarot, both of which are intrinsic to Waclawiak. She promises to give me a reading the next time she’s in town.

But mostly we talk about a life spent chasing dreams, and the dreams we continue to chase.

Fantastic interview.

Awesome! Love the photos of Karolina's open palm.