A Ramble Through Roxbury with Dave Eggers

"I don't know if you've ever had that experience, where you feel like you're running downhill when you're writing?"

“Well, right now I’m working on a short story about the Donner Party.”

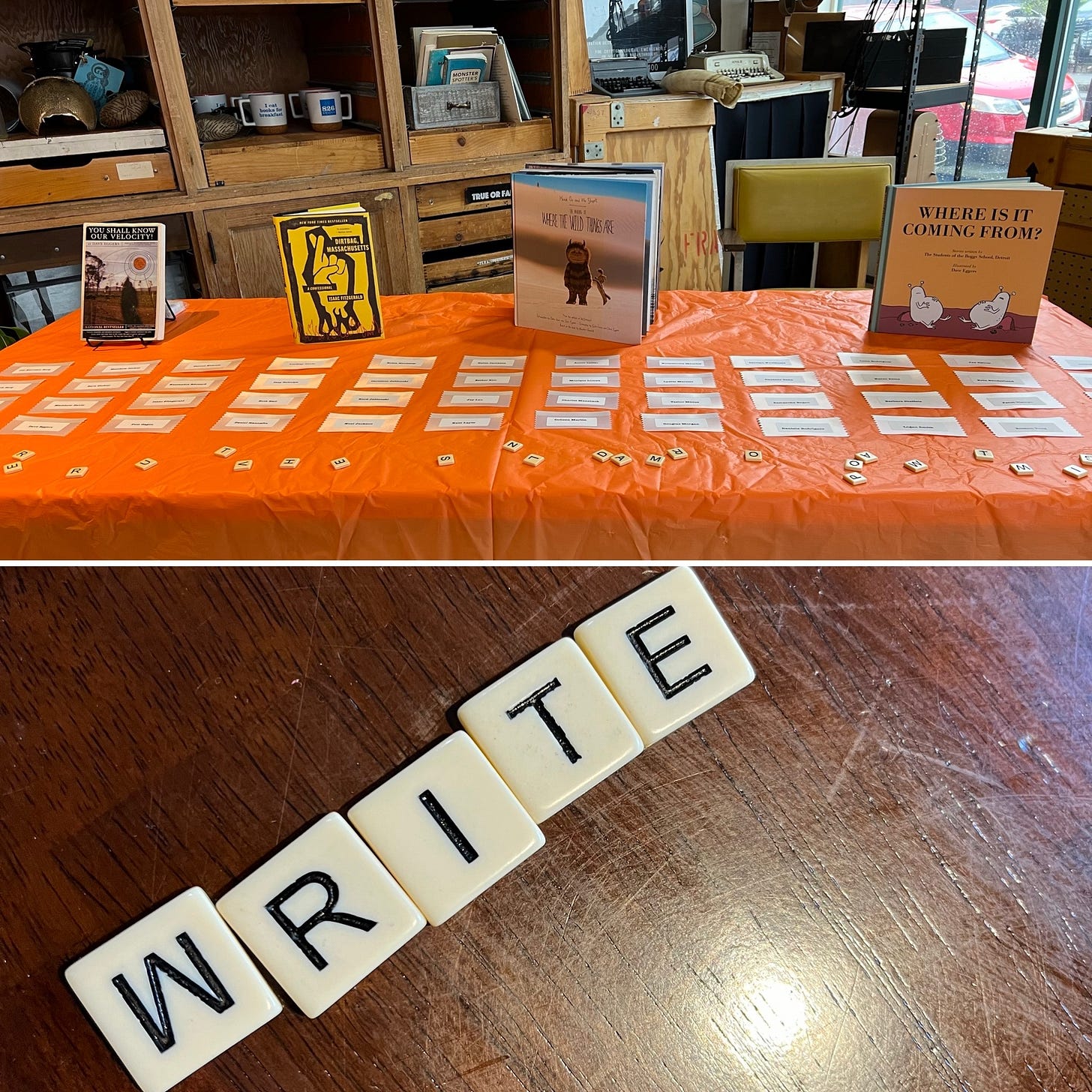

Carlos Mejia Soto is talking with a couple of board members of 826 Boston, a nonprofit tutoring and publishing center for students K-12 in the greater Boston area. Carlos—himself an 826 student—will be going to Emerson College in the fall with a full ride to study creative writing, and is here today to read a poem and then share the stage with author and 826 co-founder Dave Eggers.

It’s early on a rainy Sunday morning. The purpose of the event is to show appreciation for the 826 Boston community and, hopefully, raise a little money for the organization. There are fresh bagels, warm coffee, and the room is full of staff, volunteers, board members, patrons, and local school teachers. I’m up from New York to moderate the discussion, having recently built a relationship with 826 Boston, and (less recently) worked for both 826 Valencia and Eggers’ publishing house, McSweeney’s, when I lived in San Francisco. After the event, Eggers has agreed to go for a walk.

We’re in the Boston neighborhood of Roxbury, not far from where I spent my early childhood years growing up on Mass. Ave. Once the bagels have been eaten and the coffee drank—Carlos having brought the house down with a poem he wrote in the sixth grade, but recently updated—Dave and I set out into the wet, gray day. The night before, while doing a little research, I was surprised to see Eggers’ birthplace listed as Boston, Massachusetts—same as my own.

That fact, which I was unaware of, seemed as good a place as any to start.

Isaac: So you’re originally from Boston?

Dave Eggers: Well, I don’t know if I can say that. I was born here. Never lived here.

I: Your parents were living here?

DE: No. My mom’s side, the McSweeneys, are from here. They came here from Ireland, came to Roxbury actually, in about 1860. My mom grew up in Milton, and her dad—Daniel McSweeney—was a chief of obstetrics at a Boston hospital. So most of his grandchildren were born at the hospital where he worked. My dad was working in New York at the time, which means I was born here in Boston and then headed back to New York a few days later. I never lived here.

I: So your parents came up for the sole purpose of you being born at the hospital where your mother’s father worked?

DE: Yeah. He didn't deliver me or anything like that—because you don't deliver your own grandchildren—but his colleagues delivered all of us.

I: Then New York. When did you get out to Chicago?

DE: When I was three.

I: Those were your stomping grounds, yeah? Outside of Chicago. That’s where you grew up?

DE: Right.

I: Were you always interested in books? Did you love books as a kid?

DE: No. Not remotely. I mean, books? Yes. But reading? No.

In second or third grade, we had to check out a book once a week from the school library. It was a good effort by the teachers to encourage reading, “Check out a book, read it, return it, and check out another book next week.” So I went ahead and checked out the same book for two years straight. I never read a word of it. The book had a bunch of photos of African elephants, and I just liked the pictures. I would look at those pictures, week after week, but I didn’t read much on my own. Had no interest. I was… how should we put it? I was pretty active.

I: Energetic.

DE: Energetic. I should say that I’d read whatever teachers told me to read. Assignments and what not. Also, I loved being read to in class—I remember all those experiences. But I didn't read on my own for fun until high school. So, I always tell parents, “If you have an active kid, don’t worry. It's not a matter of if, it's a matter of when.”

You need to really give energetic kids isolated downtime. You can't say, “Here's 10 minutes, read a book.” It's got to be more involved than that, quieter, calmer. It wasn’t until my freshman year in high school that I read my first book for fun.

I: You had isolated downtime?

DE: We all had one period a week where we had to meet with a counselor. Each kid in the class had a few minutes with him, and he’d ask, “How’re you doing?” Just checking in on us. When it wasn’t our turn, we were put in a room full of books and pillows. Just the books and pillows and classical music. You couldn’t do anything but read for the rest of the hour. That’s when I started reading on my own.

I: Do you remember the first book you read for fun?

DE: Dune by Frank Herbert.

I: No.

DE: I picked it up because I liked the cover. That was it.

I: That’s a big one!

DE: I devoured it. Then I read the second book—Dune Messiah. I just remember those two books being the first real books that I read for pleasure.

Come to think of it, I did read the Encyclopedia Brown books when I was a kid, but never really had that profound, consciousness-altering experience before Dune and Dune Messiah, where you really felt like you'd lived another life. I remember walking through the halls of my high school just dazed after Paul walked into the desert to sacrifice himself to the sand in Dune Messiah.

I: That first experience of a novel turning your world on its axis.

DE: Yeah. I went from there to As I Lay Dying. I didn’t understand a word of it.

I: You clearly have an interest in kids and books and the power of the written word. You have written numerous books for readers of all ages. Do you approach your work differently when you’re writing for a younger audience?

DE: Not usually. Maurice Sendak was my model, even before I wrote anything for young people. I'd worked with him for years. Sendak really loathed the idea of pandering or writing down for any one audience. He didn't want to be a “kiddie author,” he would say. So, he wrote books—gorgeous, powerful books—that happen to have pictures. That happen to have a certain clarity. Not to say simplicity, but clarity. I think the best writing for younger readers has a meltwater-clear prose style. It's a little less dense than some writing for adults, but it's no less sophisticated.

E.B. White, if you read his work for adults and then you read Charlotte's Web, there's not a lot of difference in the prose style, or even the vocabulary. Charlotte's Web just so happens to involve spiders and pigs and rats. I think that the best children's literature is that way, and there are so many practitioners of it now. Brilliant prose stylists that should be read by everybody, but somehow we categorize them as authors for younger readers, whether it's Jason Reynolds or Kwame Alexander or Katherine Applegate or Kate DiCamillo. I think all of these people are writing beautiful books, and we should feel welcome to read them at any age.

I: Not push them into categories.

DE: We've over-stratified things.

I: That’s a great way to put it.

DE: There didn’t used to be books categorized for “8 to 10 year-olds” and “11 to 13 year-olds.” Every year it gets a little bit more hyper-specific. Which is why I love the all-ages category. You don't have to feel shame if you're an adult reading them. Books that the whole family can share—whether reading together or apart—are so key.

I: How did you get to know Maurice Sendak?

DE: When Spike Jonze and I did the film adaptation for Where the Wild Things Are.

Spike and I would go up to Sendak’s place in Connecticut periodically, and we did a lot of phone calls. He was the most vivid, hilarious, grumpy, curmudgeonly, foul-mouthed, beautiful, loving person you can imagine. He taught us both so much, but chiefly he was fearless, while also being a bit—

I: Fear-inducing?

DE: Yeah. Candid. If he didn't like something, he'd tell you. But I really loved getting to know him—and getting to know his life. He lived in this little house and listened to Mozart while working at his desk.

I: Do you remember the fist time you met him in person?

DE: I do! He gave me a big hug. He was a very affectionate guy.

For much of my childhood I really wanted to be an illustrator—I drew all the time—and Sendak’s illustrations were so gorgeous, especially the Little Bear books. I learned a lot about drawing from him and had studied his work for so many years, so it was very powerful to finally meet him in person. He was such a blast. Really one of the funnier guys that you'd ever meet. Very unvarnished. Very much himself. He didn't want to be the kindly old, harmless picture book writer.

I: Maurice Sendak had teeth.

DE:He did. He really looked the part. Very intense eyes and eyebrows and hair. He was a stocky guy, sort of built like one of his Wild Things in a way.

I: That’s wonderful that you got that time with him. You still draw and make art today. Is it fair to say that drawing and writing were of interest to you by the time you were in high school—by the time you’d read Dune?

DE: Those were always my two tracks. I did well in English class. But art always interested me—I would go wherever I could find art classes that would take me. I started traveling all over the Chicago area to take art classes. When I was 15, I started going into the city to take classes at this academy to learn classical life drawing and ended up drawing from nude models.

I: At 15?

DE: It was intense. But art—drawing—was the thing I loved to do most. There's this incredible sense of calm that comes over any kid when they’re alone drawing. I've seen it so many times with active kids. If you can channel some of that energy onto the page and into drawing, you can harness all of that energy—all of that pent-up angst—and make it into something.

So art was forever. Then, once I was in high school, I started getting into the yearbook, the student newspaper, the student literary magazine, and all that. Desktop publishing was new. The Mac had just been invented. So, that world opened up. We had great teachers and advisors that were right on the forefront of this new technology. We were told we had the first literary magazine ever done with desktop publishing, and it was beautiful.

I: A student literary magazine when you were in high school?

DE: I was a junior.

I: Holy smokes.

DE: I worked on that with Dave Moodie, who went on to be my co-editor at Might magazine. So, I really credit those teachers and advisors. They really empowered us. Similar to what we were just saying at 826: when you make certain aspects of publishing—or any career—accessible to a high schooler, you show them that the space between them and the people who do this professionally is much smaller than the student’s think.

I: You make that world—which once seemed distant—seem possible.

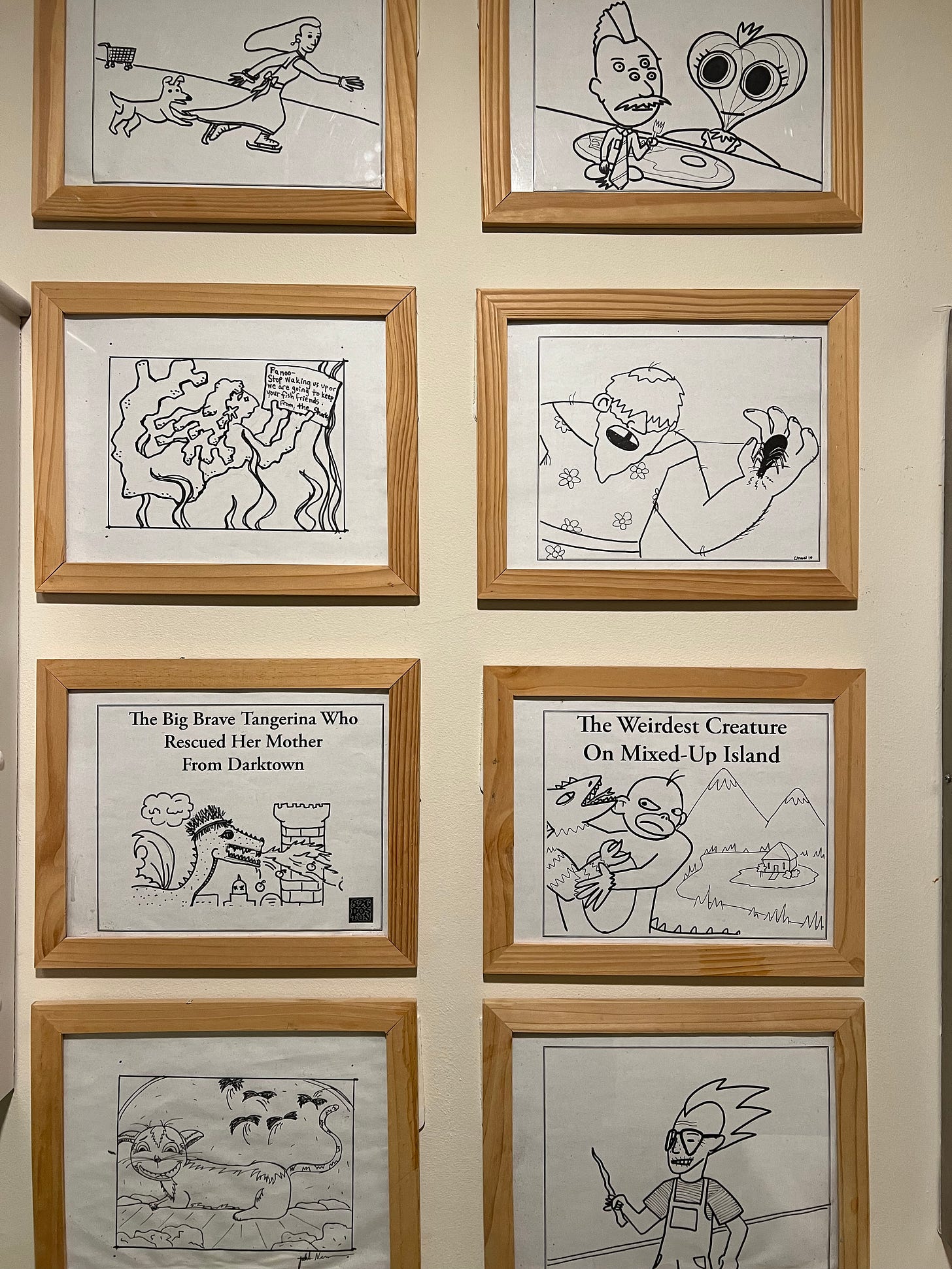

DE: We try to collapse that space. We're going to give you the tools, and it's going to look as professional as anything else out there, but it will have your words in it. That's always been the idea behind 826. Doing for students what my teachers and advisors did for me when I was a student. That's why we have professional designers and professional artists come in and volunteer. Publishers and printers make the 826 books, because it’s important the book is a real book, not some xeroxed—

I: Something where the kid is thinking, “Oh, this doesn’t look like a real book, therefore I’m not a real writer.”

DE: Right. Where it looks like it was pasted together. When you can properly typeset all of the work, you have a better chance of actually having it read by an outside audience. So that all goes back to my high school experience—and that became the true track from then on. Publishing and writing, while still working on my art. In college I started as an English major, then switched to painting, then to art history, then to journalism—which is what I ended up with a degree in. But I wanted to learn all of it.

I: I never knew you worked on a literary magazine in high school. That really puts 826 and McSweeney’s in a certain context—826 especially. You're trying to give that experience that you had to as many kids as possible.

DE: The first thing I ever did along those lines was at Might. We were based in South Park in San Francisco, and once a month for a year a bunch of high-schoolers from the YMCA would come in and we would teach them desktop publishing. We had a ball—and they picked it up so quickly, of course. We'd design album covers together. Anything. But seeing how quickly those tools gave the students power—the way that it had given us power—that was the first inkling of what then went on to became 826.

You want to go into the park?

I: Do you think that's a conscious thing you were doing? You were aware, sort of thinking “Oh, I was given this opportunity. That's why I'm trying to work so hard to give it to other people.”

DE: Yeah. In my junior year, I wrote a paper about Macbeth. I had written it the night before—or maybe even the morning of—the day it was due, which is how I always did things back then. But my teacher, Mr. Criche, had taught the play really well. He’d brought the play alive, made it vibrant and relevant. Anyway, I remember getting that paper back and at the top of it Mr. Criche had written, “Sure hope you become a writer.”

Nobody had ever said anything like that to me. Teachers had always been encouraging, but that noun I'd never heard applied to a living person. That's why I was telling some of the 826 tutors just now, “Be that person. Don’t hold back when it comes to authentic praise.” Just like Carlos was talking about the people that had shown a light on him — you never know. You sometimes assume they're getting affirmations all the time, but you never know.

I: That's absolutely right.

DE: Also, you never know which one of those affirmations is going to be the one that sinks in—or when. Maybe it comes at the exact right time where the student thinks, “Huh, that person knows what he's talking about, and he thinks I'm good enough to do this. So, maybe that's real. Maybe that means something.”

One of those 826 tutors I was talking with this morning is a PhD candidate in biomedical engineering. Maybe she works with some high schooler that she sees something in, and says, “Have you ever thought about going into biomedical engineering? You have a good brain for that.” Most likely, she's the first person to make that connection, and that chance encounter might alter the course of that kid's life.

So, you do have to speak up. You do have to say things when you feel them, and you can't be miserly with your praise. Anytime you see something good, you've got to say it. This notion that kids are overpraised today is such a joke.

I: Or even if a few kids are overpraised, where’s the harm in that? “Oh no! What a horrible thing.”

DE: “There's too many good things in the world. Let's have less of that. Let's have less affirmation and less praise. Goddamn it.”

I: Plus, kids are so hard on themselves.

DE: They really are.

I: There’s so much information—

DE: They’re tired. They've got more information coming at them from more directions than any generation in history.

They’re judged more, too. So much judgment. I mean, how many people judged us growing up? We had our friends, maybe a handful of adults every once in awhile. But now a kid might receive a flood of anonymous messages, people talking online about whatever they wore to school yesterday, anything really.

So, if you can be that person that focuses on the positive, “Hey, you did something really interesting here. You've unintentionally written this poem in iambic pentameter, and that's what Shakespeare wrote in, and that's really cool.” And they're like, “What?” That can happen with that long, one-on-one connection in a tutoring session, where it's two people chatting.

I was in Chicago a few weeks ago and doing after school tutoring at 826 Chicago. There were these two fifth graders, and they were buddies that had met at the space. They were very advanced. Doing their own thing. Tutoring is going on at the main tables while they're in a corner writing the most insane, satirical, form-bending plays.

I: They’re there to use the room and the supplies, but they’re driving their own ship.

DE: They were supporting each other. Egging each other on. “You should end here...” or “What about this?” Then, when they read their work out loud to me, they kept giving each other credit. “Well, this was their idea for this character's name.” And other kid would cut in, “But he was the one who helped me with figuring out this plot point.” We ended up just talking craft together. The two fifth graders and me.

I: What a lovely moment to witness. That level of creativity and camaraderie.

DE: I totally forgot they were fifth-graders and I started getting into it, too. “How did you do this? Where did this idea come from?” Because they truly had done some extremely sophisticated stuff on the page.

Of course, this is all happening a few feet away from a whole bunch of seven-year-olds just trying to get their homework done. Which is great, too. That 826 can be this safe space for all of these kids. One of the two fifth graders that were working on the play is non-binary. 826 is this place were they feel at home, where they found their best friend, and they're only going to find that fellow writer—that writing partner—in a place like that.

I: And now they get to make art together.

DE: With adults encouraging them. Instead of saying to them, “Well, this doesn't make any sense. I don't know what you're even saying here. Why can’t you write a standard essay?”

I: You are not a fan of the standard essay, I take it?

DE: I've had kids tell me so many times that they've been told, “Write a standard essay.” What could be worse in the whole world—what could be stupider—than the words “standard essay”? Who was ever rewarded in the history of literature by writing a standard essay?

The only thing that's ever been rewarded in writing is originality and passion. So, when you strip all that away and you say, “No, no, no. We're not going to write with originality or passion. We're going to write something that puts you and the reader to sleep, but it'll be within this acceptable, five paragraph format.” Nobody wins! I don't want to read it, the kid doesn't want to write it. No one will ever see it.

I: Also, the kid takes that home. They think to themselves, “Oh, that’s what writing is. I hate it.”

DE: But when kids are given permission to write freely? When you see teachers do that, it’s thrilling, and the kids feel it instantly. These teachers were talking to me back at 826 earlier today; they bring their class in for a field trip, and suddenly their students are writing about giant sentient cupcakes that invade the moon and fight epic space battles against half-worm, half-cats that live in the moon’s craters. That's so powerful to do that even once, to say, “Anything's possible, everything's accepted. Sentient cupcakes? That’s original, that’s great. And you know what? We're going to print it.”

I: To that point, I know it's not exactly giant sentient cupcakes and half-worm, half-cats, but your new book, The Eyes and the Impossible, is about a dog—very much in line with the short story “After I Was Thrown in the River and Before I Was Drowned,” which you wrote… 15 years ago?

DE: 20.

I: 20 years ago, which is a favorite short story of so many people. A volunteer at 826 Boston actually had a tattoo inspired by—

DE: She showed me!

I: Did she she tell you she has two?

DE: She did, yeah.

I: Why do you think that short story resonates so strongly with so many people?

DE: Well, when I wrote that short story—that was the most fun I'd ever had writing. It was really coming from the subconscious. That’s another big Maurice thing, everything he wrote—and the reason that his books resonate—is that they're all from the deep subconscious. He was never thinking, “How do I plot this book?” No, no, no. You simply try to write from the subconscious. From the same place where your nighttime/dream/storytelling brain is creating.

When a story comes from the subconscious, something uniquely resonates for both author and reader. You feel it. “Oh.” It's down here in the darkest part of your gut. That's why people love horror, love nightmares, love dystopian stuff. It's all coming from our darkest fears, or—on the flip side—the most unalloyed, joyful part of ourselves that wants to celebrate movement and exalt in what we see and get to do on a daily basis.

That was how that short story was written, and the same is true with this novel. I always wanted to get back to that voice—and once again, the book was the most freeing, most fun I could possibly have while writing. At some point you have to make sure it has a plot, of course, and that things flow from one scene to the next. I don't know if you've ever had that experience, where you feel like you're running downhill when you're writing? It’s incredible. I don't have to pause. I don't have to think about what I am writing—

I: I don't know why I'm writing “fuck ducks,” but fuck ducks.

[Editor’s note: This seemingly insane comment from me will make sense when you read The Eyes and the Impossible.]

DE: Exactly. And the reader responds, “That's how my brain works, too.” There's an echo that we recognize. “Ah, that sounds like truth.”

I think when we over-sanitize and overthink and over-intellectualize storytelling, we get away from that primal connection, which I think is the source of the most memorable stuff. Not always, but—

I: The stories that stay with us.

DE: The stories that stay with us.

I: The stories that have us walking down our high school hallway after finishing Dune Messiah thinking, “Whoa, shit. What was that?”

DE: They speak to something really elemental and inexplicable.

I: A core thing about The Eyes and the Impossible—and about “After I Was Thrown in the River and Before I Was Drowned”—is that, for me, they’re about freedom.

What do you think it is about freedom? So much of writing from the subconscious explores the darker side—horror and dystopian—yet your’s seems to take you to a place of joy. The flip side, as you said. Physicality. Freedom. A celebration of movement. Why is that?

DE: Let’s start with horror, because I’m actually reading a lot more horror fiction these days. The next issue of McSweeney’s Quarterly is a horror issue, edited by Brian Evenson.

My mom used to read a different horror book every night. That's all she read. The only books in the house were horror books, and she would sit there with V.C. Andrews or Stephen King or Peter Straub every single night. She’d put her hands up, around her eyes, as blinders so she could read. She’d read there in the living room. I was scared of everything at that age, so just the covers turned me off. I never even saw a horror movie until college.

But again, the storytelling is incredible. I retain the horror plots, the horror characters, and the horror moments much more than I do a lot of other fiction, and there's a reason for that. I think Stephen King, for example, is clearly writing from the subconscious most of the time, and you feel it. He's simply letting it flow. I think that his prolificness has something to do with the fact that he's not second-guessing where the primal part of him tells the story to go. That's my uninformed theory.

I: That sounds like a very good theory. So you’re writing from the subconscious, but this is a book for—I don’t want to say “Young Readers,” but maybe “All Ages” would work—

DE: I didn't change a word—didn't edit one single word—for any one audience. What you read was exactly how it came out. I definitely didn't think about it for middle grade, although, again, that's how Knopf has it categorized—but they have to categorize it, I guess.

I: Of course, for bookstores and where to put it on the shelf—

DE: Right. But to your question, there are some dark moments in this book.

I: That’s true.

DE: Towards the end, especially, I’m writing and thinking, “There's a reason some inner voice is telling me to have this spiraling, performative”—

I: “Beautiful,” uh, well, I don’t want to ruin it for readers but—

DE: Of course, but you know the scene I’m talking about. So, is that something that needs to be in a so-called “middle-grade” book? I don’t know. But, I was glad that nobody questioned it. Nobody questioned all of the “God is the sun” bits. I actually did think—and it still might happen at some point—that the book gets on a banned book list because it's promoting paganism. But Taylor Norman was the main editor on the manuscript.

I: The best.

DE: She made some key edits, but never second-guessed any of that stuff. I’m grateful to her for that.

Oh wow, we’re back at 826 Boston.

I: Sometimes I know what I’m doing.

DE: A good sense of direction. I generally find my way back, too.

[Editor’s note, or more of an… Editor’s confession: Time was limited. Dave had a book signing at Harvard Bookstore across town before an event that evening at the Boston Public Library. In order to keep our conversation going, I offered to give him a lift. We are no longer walking, but driving in my Jeep. I hope you’ll find the discussion worth this betrayal to the core concept of Walk It Off.]

I: So, you didn't change a word of The Eyes and the Impossible. This is exactly the book you wanted to write?

DE: Yeah.

I: Without giving too much away, the setting of this novel is very… San Francisco-influenced. Golden Gate Park, specifically. Is it fair to say you love the Bay Area?

DE: Of course. When I first moved out there—our first rental was in the Berkeley hills with a hundred-mile view. The place had three bedrooms and rent was wildly cheap.

It's so easy to fall in love with the area, especially coming from the Midwest where—people should know this if they haven't seen the Midwest—the highest hill that I had ever seen growing up was maybe 30-feet high. It was a man-made hill on a nearby golf course where we would go sledding in the winter. But that was it. 30 feet. That was the highest point for hundreds of miles.

I: Then all of a sudden you come to this hill-filled paradise.

DE: It was astonishing—and the colors. The availability of oceans and bays and forests. Everything is so extreme. I'm a color person, so I prefer bright, vivid, irrational colors—no offense to the tableau we're looking at right now in rainy Boston, but the city palette is not always my thing. I love so much about cities, but the palette, which is gray, is generally not—

I: As enticing. You even describe it in the book. You call the place beyond the park the “gray space,” right?

DE: If you know Golden Gate Park, everywhere around there is pretty gray in contrast. You have the Sunset grid that is pretty gray, and the Richmond—where I lived—is very gray.

I: But there is so much green, and even wilderness. Something I miss about San Francisco is how, if you drive an hour outside of the city—or even half an hour—you’re in the wild. In New York you can drive for two hours outside of the city, and you’re simply in… New Jersey.

DE: Chicago is the same way. Now, Chicago is beautiful in terms of controlled landscape, but outside of the lakefront, they haven't left a lot of open space. It's striking when you compare it to the West, where there’s still so much wide open, natural, untouched space.

It's so important to that sense of freedom that Johannes—the dog in The Eyes and the Impossible—talks about. It's also something that I desperately need on a daily basis. To feel close to those open spaces. The times in my life when I've lived in closer, tighter proximity without access to open land, I've been a little less happy. That’s partly why I started writing on a boat.

I: You started writing on a boat?

DE: We finally got WiFi at home, because my kids needed it for school, and I can't work where there's WiFi. I feel boxed in. So, I got this little sailboat that's smaller than this car we’re in—it's big enough for one person to sit inside—and that's where I write. It's docked on the Bay.

I: I can’t explain it, but it really makes sense that The Eyes and the Impossible was written on a boat.

DE: Some of it had been written before, but yeah. A lot of the novel was written on the boat.

It’s a problem I've been trying to solve ever since I started writing for a living. I want to be outside, exploring the world, but in order to write you have to spend so much time inside. Alone. That combination of feeling you're free—because you're very blessed to be able to do this for a living—but at the same time, you’re locked inside for eight hours a day, which has really rankled me, really bothered me, for the last 20 years.

But now I'm in a tiny boat. It's open. I have a little roof over my head, sure, but I'm mostly outside. It’s the first time I've felt, “Here's the balance. I get to be rocking slowly in a boat with the cabin open to the sky and birds and seals and herons and sea planes going overhead, but then I can still type on my 19-year-old laptop.” It feels right.

I: Listen, a boat is the dream.

DE: It's a lot cheaper than a real office—

I: I was about to ask. But, especially in the Bay Area, there’s a history of people living on boats—

DE: There is! A fascinating history. There are people on my dock that live there, and their rent per month is maybe one-fifth of the average rent in San Francisco. It’s a way of living that I'm really interested in, because they've got something figured out. Very free.

I: Shel Silverstein lived on a boat out there, right?

DE: He did. He lived in a houseboat in Sausalito. It went up for sale five years ago, actually.

I: Really?

DE: It was 900 thousand dollars.

I: But it was Shel Silverstein's.

DE: But it was Shel Silverstein's.

I: Well, your searching for freedom while writing this novel makes a lot of sense to me. Because freedom is very much at the core of this book. Freedom. Movement. An appreciation of life, as you were saying.

Aside from the boat, did you also, I don’t know, spend a lot of time at a local dog park? Study animals, in anyway?

DE: We got two cats during COVID.

They're free-range cats. They have no collars. We don't tell them where to go or anything like that. We see them often, but they're also welcome to do whatever they want to do, and to see them out in the neighborhood and running through the woods—they hunt a lot—it was a little bit of helpful last-minute research. Because they for sure exalt in their speed. They for sure appreciate beauty. They definitely have complicated souls.

There's two now, but one of them is a replacement. We started with two, and one got hit by a car really soon after getting him, and the other cat grieved in a way that was so wrenching and profound. He went missing first, and the second cat was yelling at us, saying “Where is my friend? Where did he go?” He would go out searching, every day looking for the missing cat. He would come back having spent the day looking, and you could see this total depletion in his spirit. Until finally, after a week, we found the missing cat. He’d been hit by a car right down the block. So we showed the other cat the dead body. Then there was another whole month of grieving, but at least he knew. You could tell it brought him a bit of peace.

I: He was no longer searching for his friend. That's wild.

DE: Before he saw the body, he would get up on something high, so he was eye-level with us, in order to yell at us. He wanted to be sure we saw his eyes. He would find the highest point that was eye-level and start meowing at us. “Go find my friend. My friend is missing.”

I: That’s heartbreaking.

DE: It was fucking intense. There’s real complexity there. These animals have souls.

On the other hand, they know beauty. And they know how to play. I see seals outside my boat every day. Seals have nothing to do.

I: The dogs of the sea.

DE: They have the best life.

You think, “Man, they could feed themselves in half an hour a day. The rest of life is just downtime.” These seals have it all worked out.

I started kayaking maybe 10 years ago, and when I’m out there in my kayak seals will come up to me, and sort of say, “Hey, what's up? Where are you going? I'm going to follow you for a little bit. Now, I'm going to go over here. Watch this!” I think there's very little difference in the way that they see the world and the way that they can find joy in it, and just knowing how good they've got it. They have that sort of Labrador/Retriever kind of personality where it's all good. “As long as I can swim, as long as I'm free, it's all good.”

But conversely, when any of these animals are captive in any way, you find all these other issues, right?

I: Right. I think it's orcas, you know, killer whales—if they're held in captivity their fins fold down. And nobody really knows why. They're just sad.

DE: Is that right? So that’s a pretty clear lesson. And it isn’t any different for us, as humans. We’re animals. We need the woods, the beach.

I: It’s interesting to me that you have to get away from WiFi in order to work, because, in a way, I feel like that was one of the initial promises of the internet. An untethered-ness. “You don’t have to be at the office, you’re online.” But then, at some point, it sorta flipped. It wasn’t, “You can work from anywhere.” It became, “You’re always working. You’re not free from the office, you’re carrying your office in your pocket at all times and it buzzes constantly for your attention.”

DE: I wrote for Salon early on, and there were blogs like Suck.com coming up, which were all about that new freedom — just write it, post it. Back then, you’d put something up, and then you’d be done. I worked part-time at Salon every day, from 9 to noon. I posted my section, and that was that. I could go home, do other things. But then sites started thinking, “No, we've got to post every hour.” Who the fuck decided that? Some maniac decided it had to be hourly, as opposed to, say, how you read the paper in the morning. You read the paper and then you're done, you go about your day. But everything—and it started with television, CNN, all those channels—became 24/7. But nobody really wanted it. Nobody needed to read that much content online. And I don't think it was more profitable, either.

I: If anything, it fried people.

DE: If it was wildly profitable, it would have translated into dollars. But it didn’t. Yet you still have to keep hiring more and more people to create more and more content and then you find that there's not enough people to read all that stuff.

So you're saying, “Well, shit, why wouldn't we just put three great articles up every day, as opposed to 30 crappy ones, and half of them written by AI now?”

It's happened a thousand times in human history. Chasing things that nobody really wants and aren't good for us. I compare it to the industrial food of the 1970s versus organic food now. We know that mass-produced, mass-processed food makes us ill. But for a while we thought it was space-age wonder food, right?

I: Because it was easy.

DE: It was easy, and you could make a thousand times more of it, and it was uniform and cheap. Then we realized it was making us sick.

I think that that's what’s happening with the internet. We're saying, “Wait a minute, this is the same as food in the ‘70s.” It's mass-produced, full of junk, full of empty calories. But if we can get back to the artisanal version of this—and I do think some venues are doing that, where you have a few very good articles a day—then we can regain some sanity and balance.

I: While we're on this topic—and you just mentioned your early writing for Salon—I would say that, in a way, you yourself were one of the contributors to the early voice of the internet.

DE: How?

I: For starters, Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius is a very self-aware, very self-referential book. Also, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency was one of the first humor websites and it’s still going. I think the site was very influential in forming what we’d come to think of—or maybe it’s only me, but—the “Early Voice of the Internet.”™️

DE: Well, my memoir came out in 2000, so the internet had been around for quite a while then. The McSweeney’s website started in 1998. So, I don't know. That's a weird theory you’re proposing that I'd have to think about. But I’d probably argue that it wasn’t us, it was more something in the ether. But the style, our online style at least, traces back to Letterman, Monty Python, and much farther back than that.

I: In Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius you have that added section, “Mistakes We Knew We Were Making”—

DE: That was really an attempt to be as candid as possible and to see how far that could go. I’m sure you experienced this, too—when you write about real people and real life events with that level of candor, it can be pretty hairy. So the appendix was a way to address that.

I went back to my alma mater a few weeks ago, the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, and was talking to creative writing kids there, telling them, “The stuff that everybody remembers is the stuff where you lay it all out on the line.” It's not the clever tricks or formal devices. It's times when somebody spoke truthfully to you about something that you've never heard somebody say before. So, when it's the most untethered, the most raw—and that’s almost always the hardest stuff to publish. It's not the hardest stuff to write, it's the hardest stuff to let yourself publish. It sometimes can be very messy to publish those unguarded parts, but it's the stuff that people connect with and remember. So for you—Isaac Fitzgerald—the most vulnerable parts of your own essays cause the reader to think, “That feels true to me. That's what I live. He’s recognizing and even exalting a kind of life I know.” You probably experience someone saying that to you at every signing event.

I: Yeah.

DE: People coming up to you and saying, "How did you know? You lived that, too?” Nobody’s ever coming up to you and saying, “I love how you called back to Trollope on page 175. That really delighted me.”

Which, honestly, is what I did expect with my first book. I thought it was going to be a more formal discussion with people about how the book was written, but that's not what people ended up taking away from it.

I: The truth of it is going to be what matters, no matter how you dress it up.

DE: Because it’s that writing from the subconscious—that connection—that moves people, like we were talking about earlier. Also, the cool, distanced veneer of publishing, of writing formally for magazines—

I: Your hated “standard essays”—

DE: It’s boring to write that way, and it’s boring to read that way. But when the writer welcomes the reader in, makes them feel at home, strips away the formalities and authorial distance… I’m thinking of Tristram Shandy, or Don Quixote. Don Quixote is incredible, it breaks the fourth wall so many times. “Reader, you should know here that,” or Cervantes will quickly interject, “By the way, as an aside, while we’re telling this story,” and you realize this book was written 400 years ago. So, to jump back to the self-referential style, people have always done this. It’s nothing new.

I remember seeing John Barth speak in 1999, and he gave this litany of all of the so-called postmodernists, pointing out that the self-referential, or story-within-a-story practice in literature started in the 1500s; it’s almost as old as the printing press. Everybody that was talking to the reader directly, everybody that had a book within a book or a plot within a plot, including Shakespeare; on and on and on. Everyone called Barth a postmodernist, and would assume he and his coterie invented his kind of formal experimentation, and his point was, “This is nothing new. You're just coming up with a new name for it.”

People have always experimented with the form, have always welcomed the reader in, have always broken the fourth wall. It's such an insult to history, and it shows how short our memory is that we sometimes forget this. Anytime someone says, “Oh, this is when this period began and then it ends here.” Nothing ever began or ended on that date. Come on. This is a fluid process of cross-pollination and influence and things coming back and coming to the foreground, and then receding. It’s in constant motion.

I really wish everyone realized that it has always been—and will always be—a pluralistic mess of voices that are always there. One style never takes over completely, nor does a style ever disappear completely. So get rid of all of the stratification, get rid of so many of the labels, and realize, again, the pluralistic chaos of it all. Then I think we can enjoy ourselves a bit more, you know? Why do we hand this stuff over to bean counters and classifiers all the time?

I: In a way this is also linked to what we were saying about the internet, and social media. Who decided we have to post every hour?

DE: “Look at that number. Graph this. Put this in a spreadsheet.”

I: “We can figure out art through Excel and page count numbers.”

DE: Get the numbers away from art. They are, and will continue, to kill art. Art has to be absolutely free. Very often we cage what we love. We take a beautiful wild animal and we put it in a cage, where it’s no longer itself. We do the same thing with art. “I love this so much that I’m going to kill it and dissect it, put a reductive label on it, attach a number to it.” We have to resist that urge.

Dave Eggers jumps out of my Jeep and I do the same. We hug. Then, in a flash, he’s making for Harvard Bookstore, where he will sign copies of his new book before making his way to the Boston Public Library to appear at a fundraiser there. A busy Sunday helping support the literary community in the city where he was born, but never lived.

I have a long drive back to New York, which I’m thankful for. Dave has given me more than enough to think about, but—and this is usually how I feel after talking with him—at my core I’m hopeful. The rain has gotten worse, so I drive slowly. I can’t explain it, but there’s a real sense that one era is coming to an end, while another is just beginning. Or, perhaps, that it’s not so much about endings and beginnings, simply a reemergence of something once forgotten.

I feel more hopeful at the end of the conversation too, thank you! Loved the generosity. “Huh, that person knows what he's talking about, and he thinks I'm good enough to do this. So, maybe that's real. Maybe that means something.” 💚💚

This was beautiful! So many moments, so much hope, and yes, the feeling of one thing ending and another one beginning. "Art has to be absolutely free." Thanks for this ramble, kind sir.