A Walk in Bexley, Ohio with Maggie Smith

"If you have an elevator pitch for your adult life, you’re living too small."

“I drew a face on a potato and now Rhett won’t throw it away.”

Maggie Smith and I are standing in her kitchen in Bexley, Ohio—a suburb right outside of Columbus. On the table in front of us is, indeed, a potato with a small smiley face drawn on it.

“Rhett even made a lil’ bed for it.”

Rhett—named after the lead singer of the Old ‘97’s, Rhett Miller, who is a friend of Smith’s—is one of Maggie’s two children.

“For a while Rhett was wrapping the potato up in an Ace bandage—swaddling it—and it was sleeping on his dresser. But I was like, ‘Rhett, c’mon buddy.’ So now it lives out here on the kitchen table. He’s a cute kid.”

Maggie Smith’s entire house is filled with knickknacks and art, although the smiley-face potato appears to be the only item that involves produce. Light fills each room, and between the sunshine and the art—both child-made and adult-made—the word that best describes Maggie’s home is “bright.”

An avid fan of music—John Darnielle once turned one of Maggie Smith’s tweets into a Mountain Goats song titled “Picture of My Dress”—Smith turns off the record player that’s been quietly humming in the background before grabbing her purse and ushering me out the door.

Outside, Bexley, Ohio is also bright, and almost as welcoming at Smith’s living room.

Isaac: How long have you lived here?

Maggie Smith: I've lived in this house since January 2010. 13 years. I like to tell myself that the paint looked gray in the can, but it’s fucking Periwinkle. Crayon—fresh out of the box—Periwinkle. I plan on repainting it soon.

But yeah, 13 years. My daughter, Violet, was one when we moved in, and now she’s a freshman in high school. It’s the only house my son’s lived in.

I: Seems like the vibe is very “friendly neighborhood.”

MS: 100%. Everybody knows everybody. My neighbor across the street from me—I can see her porch, so when she’s out there with her dog and a drink she’ll wave me over and we’ll sit together.

I: Now, I know that you are very much a multi-generational Ohioan. But you’re also—you’re from Columbus, right? Born and raised?

MS: My parents grew up in Columbus. I grew up in a suburb. In Westerville. From, say, first grade until I was in college. Before that, yes. I was born in Columbus and spent my first six years there.

I: Ok, but Westerville is… not far.

MS: No, extremely close.

I: So it’s fair to say that you have roots here. Columbus, Ohio is home—going way back.

MS: Absolutely. My father’s family was originally from West Virginia—but yes. Very Ohio. Very Columbus.

This is my son's school. I like to walk by sometimes, hoping that they kick a ball over the fence. When you grab the ball and throw it back, you get to feel like a real hero for a minute. The kids go nuts.

I: This is a pretty short commute for your son.

MS: I mean, that’s one of the great benefits of the house. How close it is to this school. All the kids in the neighborhood go to this school.

I: Do they all get to hangout together afterwards? Riding bikes and—

MS: Oh yeah. They run home and ditch their backpacks and then yell, “I’m going to so and so’s house,” or sometimes they come over to our house and I’m handing out popsicles. My daughter’s school isn’t far either.

I: Did you go to college around here, too?

MS: Yes. I applied to a school in Colorado—I remember thinking, “Maybe I’ll have a grand adventure.”

But then, when I was in high school—my first high school boyfriend’s best friend went to Ohio Wesleyan University, which is a small liberal arts school about 40 minutes north of here. So we would go up there on the weekends and go to parties. I liked the people I met there—the school was very artsy. And small. And really close to home. So when it came time for me to make my decision, I decided to go where I already knew people.

I: You felt comfortable.

MS: I felt comfortable. So I ended up staying close to home for college and dating my second high school boyfriend almost all the way through. And then, when I graduated, I moved home and slept in my twin bed—the same bed I had been sleeping in since I was six.

I worked as a receptionist for a year. I answered phones and wrote poems and applied to MFA programs and answered phones and wrote poems and—you get the idea.

I applied to a bunch of different places. And, same as college, it once again came down to the grand adventure—Tucson, Seattle, etc.—or home. Columbus, Ohio. I said to myself, “I'm definitely going to one of those other places. It’s time.” I visited Tucson, Arizona. Tucson was going to be my place. But then… I got a full fellowship at Ohio State University.

All those other places? I was going to have to teach the whole time and also take out loans. I’m too practical. So, I chose Ohio State.

I: Go Buckeyes! Ok, but you were already writing poems and pursuing an MFA right out of college. When did you first take an interest in writing?

MS: I distinctly remember writing my first poem. I was 12 or 13—in the seventh grade. But I wrote that poem and then put my pen down. I wasn’t consistently writing poems at that point. I don’t think I wrote any poems in 8th grade.

Then, when I hit high school, I really started writing poems. Poetry helped me make sense of the world. If something didn't make sense, I would write it down. Or if I couldn’t figure out how to say something out loud, I would try to figure it out on paper. I don't know why, but I didn't really know what I meant until I wrote it down. Writing it down—turning that thought, or feeling, or confusion, into a poem—helped me better understand the why of it.

So I started keeping this manila folder. I would handwrite my poems on looseleaf paper and then put them in this folder, which I kept in my locker. Then I gave my locker combination to two or three people—friends of mine who I thought were cool. My friend Barb, who is also now a poet. This guy Robert. My friend Megan at one point. Anyway, they would check out my poems. Like, actually check them out—as if my locker was a library. Sometimes they would write notes and give me feedback, which would all be waiting for me in my locker at the end of the day.

I: So you were basically in a secret high school MFA program. I sold cigarettes out of my locker, you workshopped your writing.

MS: That’s right. Because I wasn't a part of the literary magazine—

I: You had a high school literary magazine?

MS: There was one, yeah. But I didn’t work on it. I wasn’t a joiner. I submitted poems once, and I remember getting them back and the only feedback was someone had written, “Too introspective,” at the top.

I: Wow.

MS: Isn't that perfect? So I figured, “Maybe I'm not that good at this, but I like it.” So I kept doing it. Eventually I shared my poems with two of my English teachers, and a school librarian, and they started taking them home and giving me feedback and teaching me different aspects about poetry and giving me reading recommendations.

It wasn't for class credit or anything. Simply something I was doing on the side. But they actually took the time to really, really, really encourage me. I’m still in touch with one of them—his name is Jim Grannis. He even came to the launch event I did with Saeed Jones for You Could Make This Place Beautiful. I called him out in the middle of the event—there's a card from him that I keep at my desk that he gave me when I graduated high school. I look at that card when I’m writing—

I: You keep it on your writing desk?

MS: I do. It's Mozart with pink hair, and when you open it up, it says, “We're not afraid to be ourselves, eh?”

I: So were you a pretty good kid?

MS: I’m not going to pretend that I didn’t make some questionable choices in high school and college, but after that I cleaned up my act a bit—

I: So you graduated from college, moved back home, and got a job as a receptionist.

MS: That’s right.

I: Then you said to yourself, “Ok, I’m going to go study poetry.” You knew that was what you wanted to do?

MS: I knew that was what I wanted to do. I had a professor in undergrad who told me, “It’s really hard to get an MFA. You might not get in. So think long and hard about whether that’s what you really want to do.” Which is why I took a year off and moved home. My thinking was, “I'm not going to have deadlines, and no one's going to be making me do it. Under those conditions, will I still want to write poetry? If I'm still doing it, and it’s still making me happy, then I feel I've earned the right to pursue it.” So that’s what I did.

I: We don’t have to name ‘em all, but Ohio has a lot of colleges.

MS: Ohio does have a lot of colleges.

I: There also seems to be a strong literary scene here—especially in Columbus. You just mentioned Saeed Jones, who lives here. Hanif Abdurraqib is famously from Columbus. But there are so many writers and artists who live in the area. Do you think that’s because of all the schools?

MS: I’m sure that’s part of it. Between the state schools, the community colleges, the liberal arts schools—that’s a lot of writers teaching, as well as a lot of undergrad students and grad students, which in turn leads to a lot of reading series. There’s also a lot of performance spaces. That’s the Drexel Theater right over there. That’s where Saeed and I did the book launch. It’s such a gorgeous building. They put my name and book title, You Could Make This Place Beautiful, on the marquee and left it up for two or three days—I kept driving by on my way to the grocery store. I mean, that’s the local art house theater, and it’s been in this neighborhood for years. I saw movies there in high school and in college! So to see my name up there, it was really special.

I: So you keep writing the year after college, and you decide to apply to MFAs. Was there a plan past that?

MS: No. I had no idea what I was going to do for a job. The only poets I knew were college professors, so I thought that I’d maybe do that. Becoming a professor seemed somewhat more possible back then. But even then the prospects of becoming a professor were slim. So I decided to simply use the three years as a type of immersion—

I: Immersion?

MS: I treated my MFA like a three year apprenticeship. I wanted to really soak it up. Write poems. Live off the very modest stipend they paid me. Cover my impossibly cheap rent and that was it. My hope was to really focus on the work.

I: Where were you living back then?

MS: I was in Grandview, which is another little suburb that’s close to the OSU campus. But I moved every year for many, many years. I lived in the Short North, and Victorian Village. Harrison West and German Village and Clintonville. Every cool, walkable neighborhood, really. So long as it was on the bus line. If the neighborhood was on the bus line, I could live there.

I: Were your poems being published at this point?

MS: My first poems were published by Poetry Northwest. The poems were actually taken from my MFA application—that was the summer of 2000. Then I published fairly regularly while getting my MFA, so I knew I could do it. But I still needed to pay my bills, right? A lot of my friends and people in my program decided to get PhDs. Why not keep going for four more years? But I knew I didn’t want that. I saw myself as a writer, not as a scholar. I didn’t want to get a PhD in literature.

Even getting my MFA was a stretch. Earlier I mentioned my high school English teacher, Jim Grannis. When I was getting my MFA, I visited one of his high school classes to work with the students. I remember he said something about how surprising my path was because I he didn’t think of me as someone who was “scholarly by nature.” Jim knew me as this high school student who was going out to see bands a lot and clearly having a good time. As I said, not always making the best choices. So Jim didn’t really see me going the academic route back then. And he wasn’t wrong. I didn't apply to any PhD programs. I had no idea what I was going to do.

I: Back to answering phones?

MS: Maybe. But then I got an offer to do a one year lectureship at Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania. I moved there for nine months and taught creative writing classes. But during that time, I didn't write anything. So I decided to move back to Columbus and find a job that was writing adjacent. That was steady. That didn’t demand any prep from me, so that I could focus on my own writing when I was off the clock. I knew I needed to make time for my own work. To take care of myself. And part of taking care of myself was being here, at home, in Columbus.

When Elizabeth Egan wrote an “Inside the Best-Seller List” mini-profile of me for the New York Times, she asked, “How does being from Ohio feed your writing?” And I thought about it, and the answer is, “I’m not sure it feeds my writing, but it does feed me.” If you take care of yourself, you're taking care of the writer inside of you, and thus you’re taking care of your writing.

Taking care of oneself looks different for different people. Some people really need to travel to take care of themselves, and thus take care of their writing that way. Some people really need to be close to their family to take care of themselves, and others need to be as far away from their family as possible. That’s how they take care of themselves and their writing. For me, I’m a deeply rooted person. I like a lot of stability. I like feeling part of a community—

I: Do you feel supported by the community here?

MS: Absolutely. I feel supported by my community. I feel supported by my family. I feel supported by this environment.

I: You feel supported by Columbus?

MS: I feel supported by Columbus, yes. I grew up in this area. I went to college in this area. I went to grad school in this area. And then—save one nine month trip to Gettysburg, PA—I stayed.

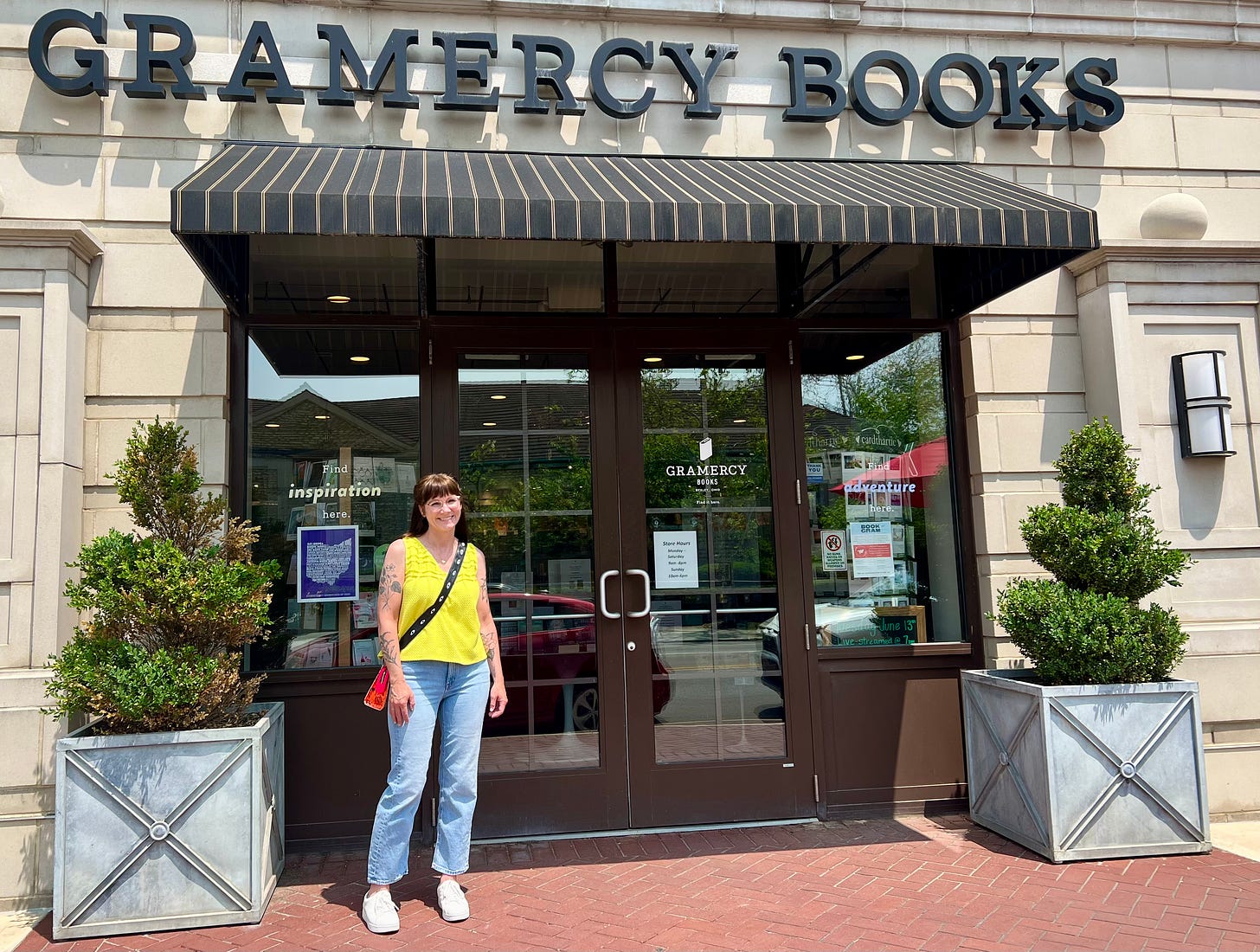

[Editor’s note: At this moment we head into Gramercy Books, where all the booksellers seemingly know Maggie. Sometimes fan mail for Maggie is delivered to the store, and they have a small bundle waiting for her when we arrive. Maggie slips the envelopes into her bag.]

I: Something I said often—earlier in my life—is that gambling is the one vice I don’t have. But then I realized I do have that vice, it’s simply that publishing scratches the gambling itch for me. As writers we gamble with our time, with our stories, with our money, with, at the risk of sounding dramatic, our lives—or at least our livelihoods. We take risks—risks that often don’t pan out. Do you find the community here in Columbus helps you take risks as a writer? As an artist?

MS: Oh, absolutely. I take bonkers risks.

I: Being a poet, for one.

MS: Being self-employed since 2011. Being a single parent. That’s why the stability I mentioned earlier is so important to me—not to mention the community. I haven’t merely spent my entire life in the state of Ohio, I’ve spent my entire life in central Ohio. The same 20 minute loop—running past the same streets and stores and people over and over and over again. But because of that—because, say, 80% of my life feels so incredibly settled, I’m able to go nuts with the other 20%.

I: You can take big swings—

MS: Being so grounded—so rooted in where I live—allows me to be untethered artistically.

There are times when I’ll be having a shit day and someone I know will simply reach out, “Hey, can I come over?” Or someone will drop off a cinnamon roll from Kittie's Cakes on my front porch with a note that reads, “I got your address from the middle school directory. Seems like things have been tough lately. Enjoy.”

When I say this place feeds me, I mean people here quite literally feed me.

I: Do you feel like a representative of Columbus? An ambassador? Again, at the risk of sounding dramatic or grandiose, but if Columbus had an NBA-style team but for artists, is it safe to say you’d be on it?

MS: I don't necessarily feel representative. I’m me. I represent me. But I think one good thing about thriving where you're planted is that it shows other people that they can thrive where they are, too.

I: They can build in the same way.

MS: And, if they’re lucky, find the same nourishment that I have.

I: To turn for a moment to You Could Make This Place Beautiful—was it difficult to release such a personal memoir when you’re so deeply rooted in this community? A place where everyone seems to know your name? Or were you prepared? Did you feel comfortable, after publishing poetry for so long?

MS: No one's ever prepared. Poetry really didn't feel much like preparation, to be honest, because in a poem there's a speaker. “This isn’t me, it’s ‘the speaker.’” In a poem you can deflect.

With that being said, I don’t feel terribly exposed. There’s an asymmetry with memoir, of course. People who I meet who have read the memoir certainly know more about me than I know about them. But as I was saying before, I feel really cared for here. Anyone I’m close with already knows what’s in the book. They've watched me live here. They've watched my kids grow up here. They've watched the hardships of the last five years. And people here—

I: Are supportive.

MS: Super supportive.

Earlier this year, my refrigerator started fritzing out. I was in a total panic, but got it together to take some measurements and order a new refrigerator online. When the delivery guys got to my house, though, they couldn’t couldn’t install the fridge because my place is almost 100 years old. I didn’t know what to do.

The delivery guys told me to call a plumber as they left, but before I did that I complained about the situation to my neighbor Shawn. He texted back, “I’ll come over tomorrow,” and sure enough he came over the next day and redid my plumbing so the guys could come back and hook up the refrigerator, no problem. Shawn simply said, “Venmo me”—and the amount was way less than a plumber would have charged, and a plumber certainly wouldn’t have come so quickly. Also, while this was happening, all my perishables were at my neighbor Wendy’s house across the street, so I didn’t even lose any food.

I know I can text my neighbors or friends anytime and say, “Hey, I need help with X,” and they’ll help me. And they know they can do the same with me.

I: You said you’ve been self-employed since 2011. What were some of the jobs you were doing before that?

MS: After I came back from teaching at Gettysburg College, I got a job working for a children's book publisher. I would read the slush pile, or write jacket copy. Then I worked for the Junior Library Guild, reading children's books at the galley stage and writing catalog copy for them. Next was McGraw Hill—I worked in educational publishing for a few years—working on English and language arts textbooks for elementary school kids. And, finally, I went to Zaner-Bloser—which is owned by Highlights for Children but headquartered right here in Columbus—doing the same thing.

I: You found what you were looking for, like you said—writing adjacent jobs.

MS: Yeah, I worked in educational publishing for most of that time. A regular job where I sat in a cubicle, worked, and then would have downtime to write poems. Writing during lunch breaks, or if I finished up early, that sort of thing.

I: Why’d you make the leap to freelance?

MS: Well, after Violet—my eldest—was born, I started noticing how much time I was wasting at work. Neither efficiency nor speed are rewarded at an office job, right? They just give you more work! Either that or you’re killing time. So I would sit there, looking at the clock every day, already done with my work but not able to go home—I just couldn't wait to physically get my hands on Violet. I wanted to hold that toddler so badly. I wanted to take her to the zoo.

Then I got an NEA grant. $25,000 is a lot of money for poetry.

I: It sure is.

MS: But not enough to live off of it for years, or anything like that.

I: Nobody’s buying a boat.

MS: Right, but I figured it could be a safety net. So I left work and went freelance—I figured if I fell flat on my face and couldn’t get any clients or make any money, the grant would help while I figured out my next move. But honestly? There was a lot of freelance work right away.

I: So similar work to what you’d been doing—copy writing, catalog writing, slush-pile reading—but more on your own time and setting your own rates?

MS: Exactly. It gave me more time to focus on raising my kids and to work on my own writing. Eventually I moved into freelance editing and helping other poets and writers with their work, too.

I: This whole time, though, you’re publishing poems, correct?

MS: I published my first few collections while I was working in educational publishing.

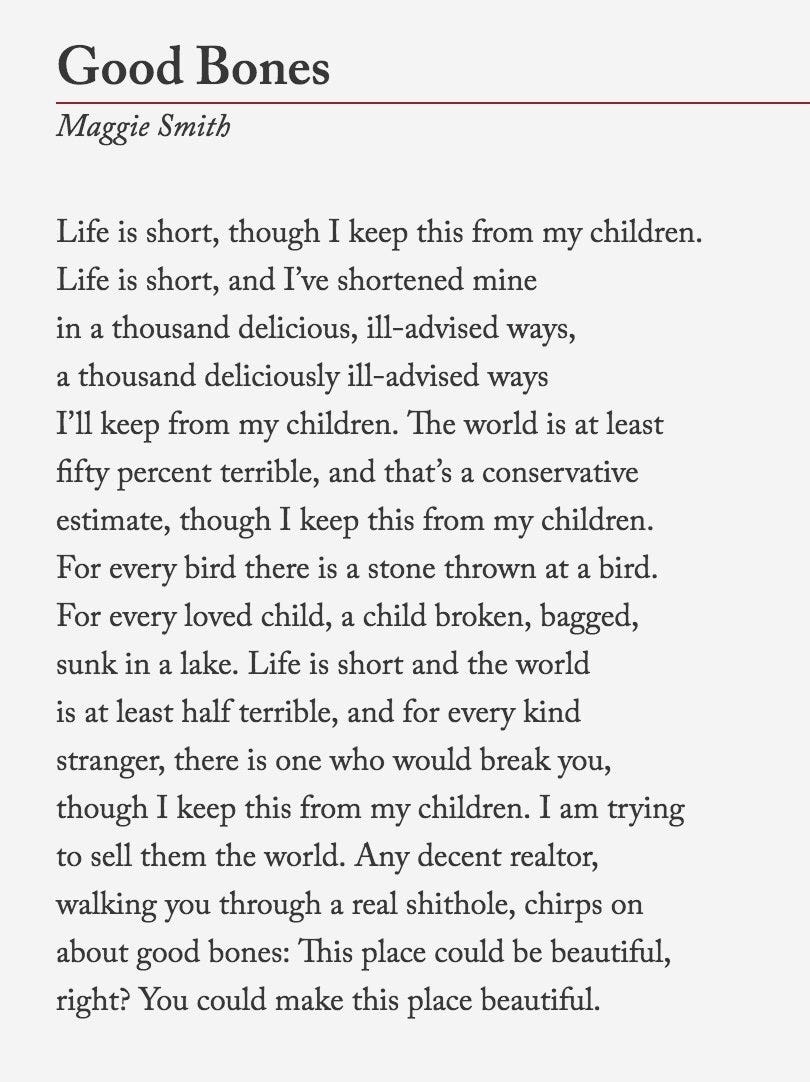

I: The title You Could Make This Place Beautiful was pulled from one of your most famous poems. When did “Good Bones” happen?

MS: I wrote “Good Bones” at a Starbucks right here on Main Street in 2015. I remember sitting there for 45 minutes or an hour, and just writing that poem. My kids were still little. Then I submitted the poem to a bunch of different places—a lot of print journals—and it got rejected everywhere, which ended up being a blessing.

I: How so?

MS: Because, when it was finally picked up, it was by a relatively new, online journal, Waxwing. Being published online allowed the poem to be shared in a way that a print magazine simply couldn’t.

I: It came out around the same time as the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando—

MS: Yes. And the murder of Jo Cox in England.

I: So, around June of 2016, but you had written it back in 2015?

MS: Yes. Before then I was online, of course, but I wouldn’t have considered myself an online person. But all of a sudden a few friends starting telling me they were seeing my poem on social media, and then journalists started contacting me. At the time I had two young children, I’d published two small press books. It was a very strange moment, all of a sudden all these people—

I: All of these people were seeing your work—reading your work—and then trying to get in touch.

MS: The truth of the matter is, if I had any idea how many people were going to read “Good Bones,” I never would have finished it. I’d still be sitting in that Starbucks trying to make it better.

I: Polishing it.

MS: Also, to have it get that much attention—

I: To go viral.

MS: To go viral, yes, but to go viral specifically because the world can be such a shit place, with these terrible tragedies happening. It was surreal and it was heartbreaking.

I: And life-changing.

MS: And life-changing.

I: When do you start thinking about writing a memoir?

MS: Well, I wrote prose for Keep Moving—

I: Which came out in… 2020?

MS: Yeah, Keep Moving was the gateway drug to the memoir. I enjoyed writing essays—I enjoyed the possibilities.

Whenever I do a poetry reading, someone will often come up to me and say, “You’re funnier than I thought you’d be.” Which… thank you? But that’s my personality! I like to make people laugh. And for whatever reason I feel more casual when I’m writing prose. I can be more voice-y—more talk-y—on the page.

I: Keep Moving stemmed from social media, right? So you did end up becoming a more, to use your phrase, “online person.”

MS: I found a real community online after “Good Bones.” Keep Moving began during the time that I write about in the memoir, but wasn’t really sharing with people yet—

I: Hard years.

MS: At some point near the end of 2018, I tweeted the first—what I’d call the first “Keep Moving” tweet.

[Editor’s note: Here’s the tweet.]

I: I remember.

MS: Clearly I’m talking to myself here. But I wasn’t ready to share what was going on in my personal life yet. So I kept doing these “Keep Moving” tweets— as a pep talk to myself, honestly, but also, they were resonating with people.

A few months after that, I wrote an essay for the New York Times’ “Modern Love” column. So it’s a gradual unfolding, right? First the tweets happen, and people were like, “Oh, something’s bad.” Then the essay came out, and people were like, “Oh, that’s why it’s bad.” But I still didn’t say much about what was going on.

So, as you asked, “Why write a memoir?” I was asking myself that same question. I never thought I would write a memoir, but now, looking back on it, that’s clearly where I was headed. I wrote “Good Bones,” then I was writing these tweets, then I got comfortable writing essays, then I came out with Keep Moving—it was all leading up to this thing I never thought I was going to do, which is write You Could Make This Place Beautiful, a memoir very much about the things I was trying to avoid talking about.

I got to a place in my life where—I described it to someone recently like this: I was stuck in a room without even knowing it, and the book was this very large piece of furniture—like an armoire—parked in front of the room’s doorway. The only way I was going to get out of that room was through that doorway, and the only way through that doorway was to move that very large piece of furniture. And the only way I could move that very large piece of furniture? Write the book. I needed to contend with everything I’d experienced on the page.

I: To make sense of it, like when you started writing poetry as a kid.

MS: Do you want to swing in here for a drink? They have this drink called Silver Dollar Pony that I absolutely love. When we cheers, we say, “Giddy up!”

[Editor’s note: We go inside Harvest Pizzeria for a drink.]

I: What was the cheers again?

MS: Giddy up.

I: Giddy Up! So, you had to move this very large piece of furniture—you had to write this book. When you realized that, though, did the book come easily or—

MS: I don’t usually write every day, but I did work on this book every day. I approached it like a day job.

I: I really loved the rhythm of your memoir. You can tell it was written by a poet.

MS: The best way I can describe it is, I have published four books of poems, but I have never written a book of poems, you know? I've only written a poem at a time. The poem shows up, and you coax it into the clearing by being very quiet and very still. Then, if it stays long enough, you can write the thing. Later—maybe a few weeks, maybe a few months, maybe a year later—another poem shows up. So it takes me many years to write a collection of poetry. I never know if I have a book of poems until I print a bunch of them out and look at them all together.

Another way to put it is I'm painting an inch of canvas at a time, without having any idea of what the image I'm actually painting is.

I: But with the memoir—

MS: This book is the only book I've ever really written as a book. With the idea of a finished product in mind from the starting point. I think—for many years—poetry saved me from thinking about writing as a business.

Maybe it’s different now, but 25 years ago when I was starting out, no poets I knew had agents. You’d basically work on your poems, eventually they would become a manuscript, and you would send that manuscript out to publishers or contests. It was a complete and utter crapshoot. Which is exactly how my first two books got published. One hit right away, and the other one took four years of sending the manuscript out over and over again before it found a home.

So it wasn’t even a question of, “Will this make any money?” It was more, “How much money will I lose submitting this?” Every time you mailed a manuscript out you were spending $30 or $40 dollars. Spending money to send it out into the void, unsure if you’d even get a rejection letter back, let alone find a publisher.

Back then publishers used to slice their rejection slips off of one single 8.5-by-11 piece of paper—so they could get around 20 rejection slips off of one sheet. You would hold up your self-addressed stamped envelope—in your own handwriting, right? You’d think “Oh shit,” when you saw an envelope in your mailbox with your own handwriting on it, and then you’d hold the envelope up—and it’d be light as hell, because it was a rejection—you’d hold it up to the sun and you could see the skinny rejection slip right through the envelope.

Which is all to say, I never thought I would make any money off my writing. I would have writing adjacent jobs, but I didn’t think I could make money from my own writing. It was more a question of how much money was I willing to lose.

I: When does that change? You write your first poem at 12 or 13 years old. We’re talking over 30 years of writing, give or take. When do you feel like you might actually be able to make a living off your writing?

MS: I mean, I'm still teaching. I still do speaking gigs. Writing is a part of my income now—a fairly large part—but it isn’t the whole pie. I'm still editing books for other poets. My Substack is part of my income—one that I’m grateful for. I’m a self-employed single parent. In a way, the need to hustle has never been greater.

And yet, I have less time than I have ever had to write. So it’s important to me that writing remains art, not commerce. I’m not comfortable putting commercial pressure on my work. I still very much want to write only what I want to write.

I: You wrote You Could Make This Place Beautiful in 2021, yeah?

MS: I started in January 2021 and wrote through the end of that year. I turned the manuscript in on New Year’s Eve. So I wrote the book in one year. I scaled back my teaching, I scaled back my editorial work. I wasn’t traveling for speaking gigs because of the pandemic. I was focused on parenting, writing this book, and making space for poems when they showed up.

I: More so than a poetry collection, did you know where this memoir was going before you set out to write it?

MS: I sold it on proposal, so in that sense I knew I was writing a memoir. But I didn’t know what it would look like at all. Much like what we were discussing at the beginning of this walk—I feel grounded, so I allow myself to take risks. I didn’t know what form this book was going to take or where it was going to go.

I: Did you know it was going to be a memoir about divorce?

MS: Honestly, I don’t think of this book as a divorce memoir.

I: A better question, what is this memoir to you? What picture do you see, now that you’re done painting it and it’s out in the world?

MS: Of course “divorce memoir” is what a lot of people see. People are so quick to categorize it—people are so quick to try and categorize everything, really.

I knew I was going to unpack things about my divorce in this memoir, but it also didn't look like any of the other breakup books or divorce books I had read. I knew it was a book about grief, but again, it didn’t take the form of other grief books that I’d read. I do think it’s a book about figuring out where you are in life, a sort of “better late than never”—doubling down on yourself at a certain stage in life—type of book. But it’s not self help. In a way, it’s a very slippery book.

I: Would you wish for no category at all?

MS: I have a hard time encapsulating the memoir in a sentence or two because it’s really about my adult life. If you have an elevator pitch for your adult life, you’re living too small. Another way to put it might be, it’s my job to write the thing, not sell it. So I try not to categorize it. But I understand that other people might want to—or need to. Still, I do think the most reductive way to talk about this book is to call it a “divorce memoir.”

I guess I would call the book a reappearing act. I talk a lot about ghosts, vanishing, invisibility, magic, and sleight-of-hand in this book. Those are metaphors I use often. That’s because I think I allowed myself to become small—to sort of be a vanishing act in my own life. I made a lot of decisions that had other people’s best interests at heart, and not my own. So I think of this book as a reappearing act. Pulling myself out of a hat. It’s not that I wasn’t there—when someone pulls a rabbit out of a hat, the rabbit was always in the fucking hat. I was always there.

I: This feels like stating the obvious, but it’s a memoir about you—by which I mean, it’s not a divorce memoir, because to call it that would be to say that you are now defined by your divorce. The whole point is that you aren’t—the whole point is that you are larger now, not diminished.

However you want to categorize it—or not categorize it—though, people obviously responded to what you wrote. What was it like when you found out you hit the New York Times best-sellers list?

MS: I was folding laundry when my agent called me. I never want to know numbers—my agent specifically tells people not to send me shit with numbers because, as she puts it, “It will freak Maggie out.” Even if it’s good, I don’t want to hear it. Of course I’ll do anything to support the book. Podcasts, interviews—

I: You’re not moving to the middle of the woods and not talking to anyone about it.

MS: Right, but I don’t want to know anything about, you know, what’s actually going on. It doesn’t help me, it simply makes me nervous.

I: So you’re folding laundry.

MS: It was five o’clock and my kids were home—or Violet was home and Rhett was out playing because he always plays until right before dinner. I was folding laundry in my living room and my agent called, because I wasn’t responding to any of the emails they were sending because, well, I was folding laundry.

When I picked up she told me to get to a computer, so I did, and that’s when I saw it. My name. Well, not really my name so much as Prince Harry's name under my name, and that really freaked me out. Because it felt like someone was playing a trick on me. Using Photoshop to prank me. It was just a huge surprise. It's still very surprising to me.

I: At the risk of labeling or categorizing—Ohio poet does good.

MS: I know I get cranky around labels. I hate it when people try to pigeonhole women writers, or parent writing, or divorce writing—as we just discussed—but you know, that one doesn’t bother me. I’ve heard people use the term “regional writer” in a degrading way. As a slam, or a putdown. But I don’t see it that way. From a commercial standpoint, “Ohio poet” is a very narrow aperture. I understand that. But that’s the label I love. I love being an Ohio poet.

Maggie Smith and I order some food and move to an outdoor table. A few friends of hers stop to chat, and a neighbor waves hello. Eventually, a woman who I noticed standing hesitantly on the street approaches us.

“I just had to say, I love your work! I’m such a fan.”

Maggie stands and talks with the woman. I can’t hear their conversation, but there’s laughter, and a brief hug. When Maggie comes back over, she asks if we should invite Saeed Jones to join us. Soon he’s ordering a Silver Dollar Pony too, and the sun is setting. A waitress kindly takes our photo.

Giddy up.

Oh, I loved this conversation. ("Giddy up" is my new favorite toast.)

Come back soon, friend! 🐴🥃