A Walk Around "Treats Crossroads" With Chloé Cooper Jones

"For me, it comes down to an obsession with devotion."

“The Fruity Pebbles cupcake looks amazing. Then again, every cupcake looks amazing.”

“Wolfgang's a huge fan of the s'mores bars.”

Chloé Cooper Jones and I are examining what’s on offer at the Little Cupcake Bakeshop in Prospect Heights. I’ve been tasked by Jones to find “a special drink and perfect snack,” a quest she is usually completing with her son, the aforementioned Wolfgang—but more on what that entails later. For now, know that it’s a delightful distraction from the sweltering hot day, one that has Chloé and I popping in and out of cafés, bakeries, and ice cream shops up and down Vanderbilt Avenue in Brooklyn.

At one point, I mention to Chloé that I feel bad going into the shops, but not buying anything. She assuages my fears.

“Isaac, peeking is normal. That’s what shops are for. You can go in and see what they have—I promise you nobody is getting upset. Don’t get too Catholic about this, ok? Besides, I’ve bought so many treats at all of these places, I promise you.”

This is something Chloé has done a lot over our years of friendship. Told me to breathe. Talked me off a ledge. Tried to make sure I see the world the way it is—not the way my anxiety-riddled brain often makes it out to be.

“Sometimes you want a doughnut, other times you want an ice cream. It’s ok to look around and see what you’re interested in.”

It’s one of the many reasons I appreciate spending time with Chloé: I’m usually learning something. Whether it’s about art, or writing, or the philosophy of living—of moving through the world. It’s almost as if Chloé, a longtime teacher, is never not conveying information or imparting a warm lesson of some kind.

Long before our snack hunt, though—before I even knew treats were the mission of the day—I met Chloé at her apartment and we set out into the hot, bright afternoon.

Isaac: Where are we?

Chloé Cooper Jones: Crown Heights. I've lived here for 15 years, total. My entire time in New York City.

Wolfgang went to elementary school right over there at PS 705. On Fridays I would pick him up from school and then we’d head across the street to the Neptune Diner, where we’d order ice cream or grilled cheese sandwiches and sit outside.

I: How’d you come to live in Crown Heights?

CCJ: I had a friend who had an apartment and said, “You can live here, but it's above a very, very loud bar.” Still, the rent was extremely cheap, so I took it—and I've held on to that deal ever since.

I: What made you want to come to New York City in the first place?

CCJ: I initially came for a writing class with Gordon Lish at the Center for Fiction in 2009. I was living in Kansas at the time, but I came here that summer and fell in love with New York. I met a lot of writers who are still some of my best friends in that class.

I: So you wanted to be in New York to be a part of the writing scene? You wanted to be in the mix?

CCJ: Yeah, I had a tremendous community here—and it felt that way immediately. I knew this is where I wanted to be.

I: You also came to New York to study philosophy, right?

CCJ: Right.

I: Do you think studying philosophy helps you as an artist?

CCJ: Definitely.

I believe philosophy is a wonderful pursuit for artists of any discipline, really, because philosophy is the practice of studying unanswerable questions. The second that something is known—or can be answered in any sort of convincing way—it's not philosophy anymore.

Astronomy, for example, began as philosophy. But once we could measure distances between stars or understood what an eclipse was, it became science. Which is true of many, many disciplines. They all started as philosophy.

So I think it's a good practice, to train your mind to sit within concepts and ideas that are completely unknowable. The unanswerable questions. Because the work of writing a book is often sitting with all these possibilities of what the book could be. What form will it take? What structure will you discover while writing it? What will your characters do? What parts of your life do you want to write about?

You could sit there forever being unable to make any decisions, because there are no easy decisions to make. Yet philosophy teaches us that—even though these questions are unanswerable—we have to take a stab at them, in order to move knowledge forward.

Which is very similar to the process of writing a book. What you could write about is infinite. The ways you could structure the book are infinite. But if you get totally bogged down and overwhelmed by that infiniteness, then you will never finish the book. How do you take a step forward when you're not necessarily sure what comes next?

I: What you’re saying reminds me a bit of that E.L. Doctorow quote—I think Anne Lamott uses it in Bird by Bird. “Writing a novel is like driving a car at night. You can see only as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.”

Is that how writing Easy Beauty felt?

CCJ: Yes. There was a lot of feeling my way forward with Easy Beauty. I wrote a lot of pages while working on that book—three or four times the amount of pages that ended up in the manuscript.

I: Wow.

CCJ: There was so much writing that got done for Easy Beauty before I even understood what shape the book would take. It was truly a process of discovering the book through the work. That was just how I had to do it.

I: Will that be your process for this next book, too?

CCJ: With the second book, I've done a lot more conceptual mapping. I’ve made decisions and have done a lot of outlining, sketching, and research—the second book is so research heavy that, in a way, it’s imposing its own structure. A necessary structure.

So much of the work that I've done for this next book has been about finding the shape. Now that I have the shape, I'm actually filling in the pages. I haven't written that many pages. I've written a lot of words, but I haven't written a lot of pages—every writer will understand what I mean by that. But overall, I feel much more confident moving forward, because I know where I’m going this time around.

I: How much of this are you figuring out on your own, sitting at your desk? Or do you work with your agent, editor—or maybe friends or a writing group—to help you plan?

CCJ: Both?

My agent and editor are so helpful in so many different ways—but a lot of the early structure stuff I’m doing on my own. That’s not because I think I’m so smart, or anything like that, it’s more that I’m really, really possessive.

I felt this way with Easy Beauty, too. It felt like, if anybody saw it—if the manuscript even saw the light of day—it would disappear.

I: Disintegrate.

CCJ: Exactly. I really needed to keep everything private. I couldn't discuss it. I couldn't show it to anyone. I didn't show it to my agent or editor until I had a full first draft.

Now, my editor, Lauren Wein, is a genius. She massively shaped Easy Beauty. She’s so good at pushing me to a point of really telling the truth. Being honest on the page—because she’ll call me out when she thinks I’m hiding, or shying away from something. If I’m being a little self-protective, or being protective of other people, Lauren will call me on it.

Lauren is such a tremendous listener on the page. Which in turn, is something I really try to be for my students. I really try to hear them on the page—and what I mean by that is, being sure to listen for the thing they really want to talk about. Often there will be a scene that you can tell holds the most urgency—this is the point the writer is trying to make. But they’ve written through that scene or moment really, really quickly. Lauren is great at spotting when I do that, and I in turn try to do it with my own students, or when I’m reading a friend’s work.

I: But you fumble in the darkness alone, first.

CCJ: Yes. I make the skeleton in the dark. I figure out what the book is in the dark. Then Lauren says, “That’s fine. That’s great. But let’s add some muscle here. Let’s put some more guts here.” The book becomes more bloody, more messy, more true—all because Lauren pushes me to be more honest on the page. More fearless.

I think every writer really needs a good second reader, whether it's an agent or an editor or a best friend or another writer that you really, really trust—you need somebody on your team who can say to you, “You’re shying away, here. You’re not being fully honest, here. Hey. You're bullshitting. Stop.”

I: “You're hiding something.”

CCJ: You're doing it subconsciously. You don’t mean to hide on the page, but it happens. We all do it. Our brains are wired to self-protect, and to protect the people we care about. So there’s naturally a certain limit to how far you can go on your own. It helps to have someone there to push you. To really listen. You have to have brutal eyes on your work. I’m thankful to both Lauren and to my agent, Claudia Ballard—they’re both incredibly good at pushing me to tell the truth. They’re both brutal readers, and my writing benefits so much because of that.

I: You also have to be open to their edits. To their thoughts, and critiques.

CCJ: Oh, absolutely. You aren’t going to benefit from help—from brutal readers—if you’re not prepared to hear what they have to say. In that moment as a writer, you have to drop your ego and be focused on one thing: What will make this book better?

I: When you and I first met, you were teaching at a nursing college in Harlem—

CCJ: Yes, all my students were New York City nurses, but they were doing a full bachelor's degree. So they had to take English, and they had to take philosophy, and sociology, and history—

I: The humanities, baby.

CCJ: That’s right. So I started there as an adjunct, then was hired full-time, and by the time I left I was the head of the Humanities Department.

I: That’s impressive.

CCJ: Well, it was a very small department.

I: Still, difficult—during COVID especially, I’d imagine.

CCJ: Really, really hard.

I: But now you’re at Columbia University. What's your favorite thing about teaching?

CCJ: The students—everyone, really. The people. I love being around people who are hungry to learn.

I: Because you yourself are someone who is hungry to learn.

CCJ: It's so cliché, but it's true. It's very intoxicating to be around people who care about the same things you care about, and it can be very validating and energizing to immerse yourself in an environment where everybody around you is in love with literature and reading the same way you are in love with literature and reading. A whole group of people who agree, “Reading books is great. Let's talk about them.”

Because, of course, everything else in our lives competes with the desire to write and make art, but if you spend 40, 50, 60 hours of your week around people who think that's really, really important, it's exhilarating.

Do you want to grab some tacos?

I: So where do you want to walk to next?

CCJ: Ok, so this is crucial—it’s time for you to make a crucial decision.

I: I’m in!

CCJ: During Covid, Wolfgang and I would walk this loop—every day, Monday through Friday—which you and I will now walk. It was a way of marking the end of Wolf’s school day—because his class was online, so we weren’t leaving the apartment, right? He’d be learning in his bedroom, and then 2:30pm would roll around and, well, we’re still just sitting there. So we started walking this loop as a way of delineating the end of his school day—around 3pm every day. A way to give structure to these structure-less days we were stuck in.

Now here’s the crucial part. The walk always includes a special drink and perfect snack.

I: A drink and a snack?

CCJ: A special drink and perfect snack. Every time we did this walk, Wolfgang would search for that day’s special drink and perfect snack. It became our ritual. Now I want to do that same walk with you.

I: A hunt to find my special drink and perfect snack?

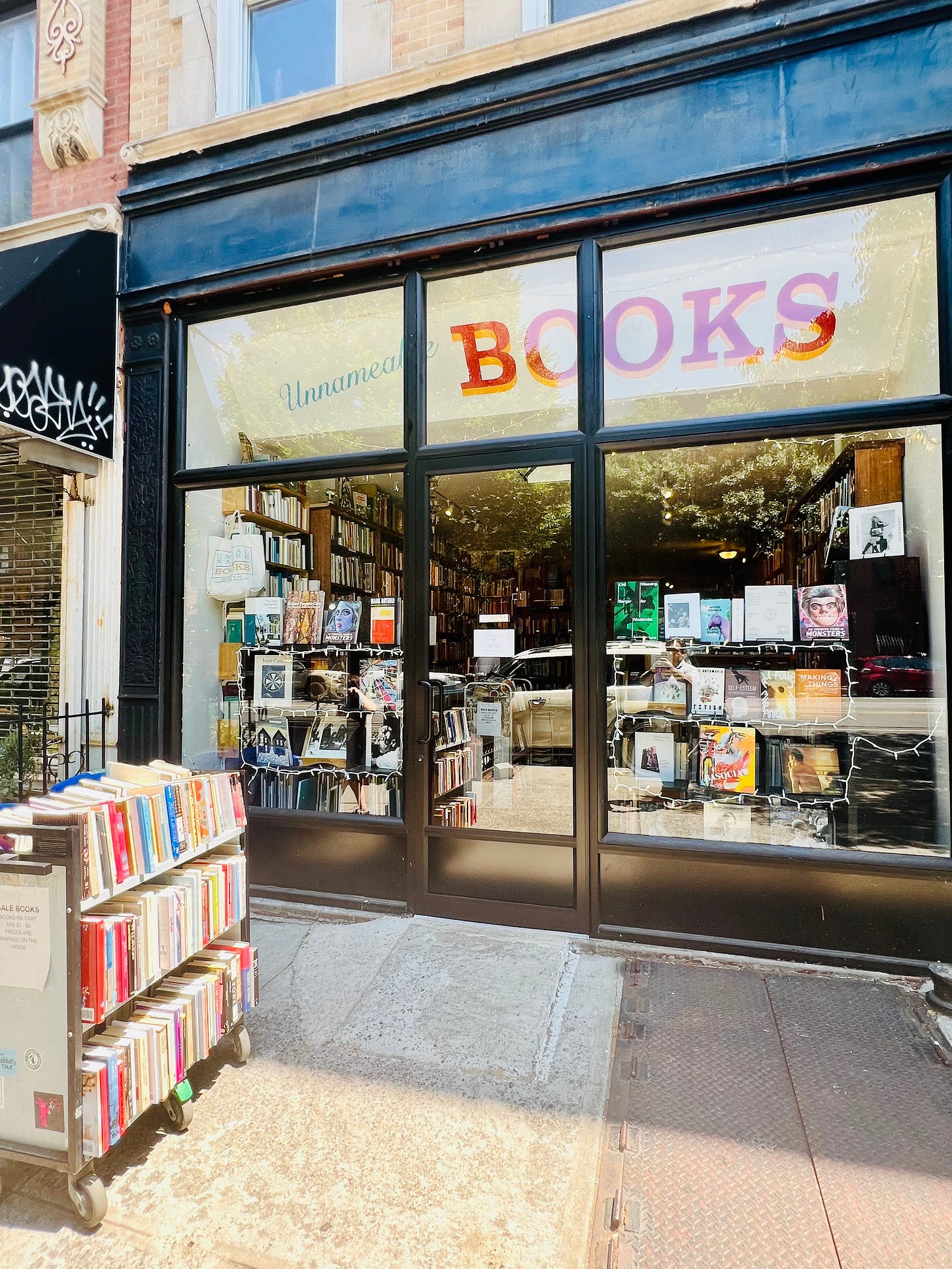

CCJ: Yes. Because we’re in the perfect place for it. Treats Crossroads.

I: Treats Crossroads? That’s the name of this area or—

CCJ: That’s what Wolfgang and I call this area.

I: Stop. I’m dying. This is too cute. Wait, so we’re—

CCJ: On Vanderbilt Avenue in Prospect Heights—we usually start at Vanderbilt and St. Mark’s. Look at all that Treats Crossroads has to offer. There’s ice cream at Ample Hills. Cupcakes at the Little Cupcake Bakeshop. Or Mille-Feuille Bakery if you want a chocolate croissant. Want a doughnut? We’ll go to Dough Doughnuts. The possibilities are endless.

I: Treats Crossroads has it all.

CCJ: That’s what Wolfgang and I would do most days during the pandemic. We’d walk down St. Marks, then hit Vanderbilt, then walk around this little radius and visit all these cute, little places—looking at all the treats on offer. Then, once Wolfgang had made his decision for that day, we’d double back to that bakery or store and buy his—

I: Perfect snack. What about the special drink?

CCJ: Well, you had a margarita at Alta Calidad.

I: Presumably Wolf isn’t grabbing margaritas on Vanderbilt quite yet. Is he going for a milkshake or—

CCJ: No, that would be too close to a perfect snack. The special drink needs to have a little contrast—

I: Actual liquid.

CCJ: Actual liquid. For example, say it was really hot out. Wolfgang would try and find the perfect lemonade. Or perhaps the special drink of the day would be a fancy spritz—

I: Like an Orangina.

CCJ: Sure, that’d be a pretty good special drink.

I: The way you said that, I feel like maybe Orangina’s a little basic for special drink.

CCJ: There are so many corner stores, and even a couple of grocery stores around here that have a plethora of unique drinks to choose from—walls of fancy seltzers, or imported juices. So Wolfgang might choose an Umeboshi Plum drink imported from Japan.

I: I’m starting to see the vision.

CCJ: I would usually hunt for a really nice tea. But we would try to change it up every day. It was helpful—breaking up the day with a walk, sure. But the special drink and perfect snack were helpful, too. I don’t know about you, but I usually start to lag in the afternoon—

I: Oh, totally.

CCJ: 2:30pm, 3pm—that’s when I really start to get tired. I start to get sick of what I’m doing. But Wolfgang and I would go for our little walk to Treats Crossroads, we’d find our special drink and perfect snack, and we’d get our energy back up for the rest of the day.

I: So that’s my crucial decision. I have to find a special drink—assuming I don’t want to count my margarita—and perfect snack.

CCJ: That’s your crucial decision, yes.

I: How long have you been teaching?

CCJ: My first semester teaching in a college classroom was fall of 2006.

I: And you’ve taught ever since?

CCJ: I took a year off when Easy Beauty came out, but pretty much. I’ve been teaching for a long time. To be honest, I really thought about not returning to the classroom once Easy Beauty came out, but then I got this opportunity to apply for my job at Columbia and it felt too good to pass up.

I: How has it been, being a part of the writing program at Columbia?

CCJ: Amazing. My colleagues are some of my literary heroes, like Margo Jefferson and Leslie Jamison. I remember reading The Empathy Exams ten years ago. It was a huge light bulb moment for me—for so many of us, right? In terms of understanding what nonfiction can do—

I: Absolutely.

CCJ: Now she’s not only my colleague, but we share an office. The caliber of writers who teach there is mind-blowing to me. But again, it is really about the students. The students are—they’re geniuses. They’re incredible.

When I’m in the classroom and my students are giving feedback on each other’s work, and they’re really pushing their classmates—or themselves—to do something new in their work—

I: When they’re helping each other not hide on the page, for example?

CCJ: Exactly. Those are the moments where I find myself thinking, “This is the most worthwhile thing I could possibly be doing with my life.”

The only thing more important to me is being a good mother.

I: Teaching is fulfilling for you.

CCJ: It feels so, so good. Selfishly good, even. Because I want to believe that all this time I give to writing means something—that I’m not wasting my life.

To be around these students who are so engaged and passionate about art and writing and the books that they’re working on, it’s the best. It’s a total dream job. I’ve never felt luckier.

I: Look at all these fancy macaroons.

CCJ: Do you want to pop in here?

I: What is one of your favorite lessons to impart on your students?

CCJ: I owe so much of my teaching—so much of everything, really—to Deb Olin Unferth, who now teaches at the University of Texas in Austin but was my professor when I was at the University of Kansas. She’s a brilliant writer and a brilliant educator.

One of my favorite ideas about writing comes from her. An idea that I often teach to my students. Although, Deb’s told me it’s not a direct quote from her—I get it a little bit wrong. So it’s become a sort of—

I: A Chloé and Deb hybrid?

CCJ: Yes.

I: As often happens with quotes and ideas.

CCJ: But I remember her teaching me this—the idea is, basically, “When you sit down to write, imagine you’re sitting down at a piano. You’re looking at the 88 keys of a piano, and think about all the people throughout history who have played these 88 keys. All the millions and millions of times these 88 keys have played throughout history. All of these different combinations and all of these different chords and structures. So many people have played these keys and created so much music using these 88 keys. Now, your job is to sit down at these same 88 keys and find the one note that only you can play.”

I: I love that.

CCJ: “It might take a lot of time to find that one note, but you have to keep searching for it.”

Because all of us are telling stories that have been told before. A tremendous number of books have already been written about all sorts of experiences throughout history. But what is that one note that only you can play? What is that one story—or one way of telling a story—that only you can write?

You have to figure out your own extreme particularity.

I: In December of 2020 you and I went on a trip to Dia Beacon.

CCJ: We did!

I: I didn’t know what Dia Beacon was, and I wasn’t familiar with the work of Richard Serra. So you taught me. When did art become so important to you? To use the 88 keys concept, why is art such an integral part of your writing—of your singular note?

CCJ: I've really been thinking a lot about this, recently. Asking myself, “Why do I want to write about art so much?” There are lots of things in this world to write about—and I'm extremely interested in a lot of things—but I always come back to art.

My second book is about a huge painting—

I: The Rose. You took me to that, too.

CCJ: The Rose by Jay DeFeo, that’s right. I keep wanting to write about other artists, too. Also, my fiancé is an artist, Matty Davis—so art has this way of taking over our whole lives.

But why do I keep coming back to art? What is the true answer to that question—and I think I’ve figured it out. For me, it’s about devotion. Devotion gives one’s life meaning, and I think that’s something that I love about art, and artists. Writing and writers. All of it. For me, it comes down to an obsession with devotion.

Because, if you’re devoted to something, it gives meaning to all of the awful tasks, the logistics and boring detritus of life. How much of your life do you spend looking for parking? Or getting stuck on the subway here in New York City? Or dealing with bills or writing emails? If you really thought about it, you’d tunnel into despair, at least I know I would. We have this very short life—and I don’t mean this in a grandiose way, it’s simply a fact—we have this very short life, and we’re always trying to figure out the calculus of that very short life.

How much time do we give to work? To paying our rent? To simply surviving, you know? Versus how much time do we give to the things that are meaningful to us, however we define that. That calculus can be so depressing, so soul-crushing, when you really look at the numbers. But add devotion? Through devotion, we can create a way that those—let’s call them “tasks of life”—that those tasks of life are a part of what we find meaningful.

For example, let’s take teaching. There are so, so many boring tasks that go into teaching, but if the meaning or purpose you find in teaching is what you get from your students, that joy of being in the classroom—if that purpose is of a high enough quality, then the tasks themselves begin to hold meaning.

I: They are a part of the overall meaning.

CCJ: Exactly. They aren’t these boring, mundane tasks that are eating up hunks of your very short life. They are done in service of the very thing that gives your short life meaning.

I: Therefore they aren’t drudgery. In a way they’re holy.

CCJ: Yes, absolutely. Another great example is parenting.

Quite a lot of boring tasks come with parenting, right? No surprise there. So much task completion. But those tasks can take on great meaning, because they're in service to something that is a core organizing principle in my life, which is being a good parent. Loving my son well. Trying to provide for him. Do I hate doing the laundry? Yes. How about grocery shopping? I genuinely hate that, too. But these tasks have meaning, because I am doing them for him.

I: You are devoted to Wolfgang.

CCJ: Exactly. Devotion turns those pain-in-the-ass tasks into—

I: Ways of expressing love.

CCJ: The calculus of my very short life is no longer soul-crushing, because the things that feel monotonous now have purpose.

I: You do them for the child you’re devoted to. Or you grade the stack of papers late at night for the students you’re devoted to. I just used the word “holy,” because this rings true of one of the plus sides of religious devotion to me. The difficult work of living is going to be rewarded, in a way.

CCJ: I didn't grow up in a religious tradition, which is also part of why I keep coming back to art, I believe. From a pretty early age, art was a divine organizing principle in my life. Truly believing that art was a valuable—a necessary—aspect of human existence. A lot of the suffering that I went through early on in my life, I told myself it was in service of art, and making art.

I’ll talk with writers who say to me, “I went through this horrible breakup, but one piece of my brain is remembering everything that’s happening so I can write about it later.” Or a visual artist friend, who tells me about a beautiful pond that he stumbled upon while on a walk, and he walked himself to the point of exhaustion because he wanted to get close with the pond, telling me, “I had to spend time with this pond, and walk around it multiple times, so that I could draw it later.” Art, for me, has always been an organizing principle to make sense of pain, loss, difficulty, struggle, boredom, and all the life-siphoning tasks we endure.

I: A devotion to art.

CCJ: Now that I’m older, there are other organizing principles. Other devotions. My family. Teaching. My friends. But all of it really is simply devotion, and devotion is a way of subordinating despair-causing realities. I spend more time doing mundane things than I do with my son, or writing, or making art, or spending time with my friends. But those mundane things are all in service of the things I love. The things I’m devoted to.

I: You mentioned your fiancé, Matty Davis. He’s an artist and choreographer, and you recently wrote a piece for New York Times Magazine about being in his work. I know you’re also interested in theater. Do you find yourself excited about these new art forms you’re exploring, outside of writing? How does it feel to be a participant—instead of an outside observer—of other forms of art?

CCJ: I, as a disabled person, grew up under a false belief that certain artistic practices were not available to me. I was really interested in the theater when I was growing up—acting as well as writing and directing. Like so many young children, I wanted to be an actress. But time and time again I was told, “Well, you can't be an actress, not with a body like yours.”

I was also always interested in dance, but again, “Your body isn’t built for that.” Which of course, is not true. But I didn’t know that at the time. But that’s true of so many things in my life—

I: The story of your life, in a way. You were told you couldn’t give birth—

CCJ: Right, yet now I have this beautiful son. Which brings us back to devotion. Because I'm so devoted to art, because I believe so intensely—with a religious fervor—that art should be a tremendous organizing principle in one’s life, the greatest gift someone can give me is expanding my artistic practice. And Matty did that by inviting me into his work, showing me how I can participate in art in new ways. It’s been the greatest gift.

Meeting Matty and having him expand my understanding of what dance can be, what performance can be—and being influenced and inspired by playwrights who really care about different bodies—it’s been transformational.

Will Arbery—who introduced me to Matty—really thinks a lot about disability, and has written roles specifically so they can only be played by disabled actors. Arbery has really expanded my sense of what theater can be.

It’s almost as if I have a whole new chamber of this “church of art” to explore. A whole new room in this church, where I can further explore my own devotion. It’s allowed me to be an even more creative person, to live an even more creative life—to question the narratives I was living under and the limitations that I put on myself.

I: Does that expansion of your artistic church influence your writing?

CCJ: Yes, I think it all feeds back into the primary craft of writing. I’m a big believer that writers should try and express themselves in other artforms—and so many writers that I admire do. Teju Cole, for example, is an extraordinary photographer. So many writers I know also paint or draw. I have a student, Randle, who also writes music and can sew and embroider really well—she makes these beautiful crafts that I can’t even fathom being able to do.

I think that it's such a gift to feel the stretch of your devotion in that way. I owe a lot of that to other artists in my life.

I: Well, if you'll allow me, I will also say that you also owe it perhaps to your own curiosity.

CCJ: Oh, that's nice. I think that's very kind. If you see me as a curious person, I take that as a deep compliment, because to me curiosity is about as fantastic a trait as a person can have.

It’s something I think is true of you, too. You’re a very curious person. I'm very inspired by people, like yourself, who seem to have a yes-ness—a yes orientation toward life.

I think one of the greatest tools that a writer can have—or an artist can have—is a genuine openness to other people. An openness to experiencing life. I try to be very curious, so I appreciate you saying that.

I: Do you ever find it difficult? Being curious?

CCJ: Absolutely. I write about that in the piece you mentioned, a bit—how fucking scared I am. I do try to be curious, but that doesn’t mean I’m also not terrified. I aim for that same fundamental “yes-ness to life,” but I’m also scared, anxious, resistant, angry, and annoyed at the fact that I’ve said yes, sometimes.

It’s important to acknowledge that it’s not easy. I’m confronting creative failure over and over again. So many times I’d catch myself saying, “I can’t do this,” which was another way of saying “I’m afraid to do this.”

I: The voice inside your head that says, “They’re all going to laugh at you.”

CCJ: “They’re going to judge me. I don’t want to do it. I can’t do it. I don’t have what it takes.” Which leads to, “I don't fit in. I don't belong here.”

I: I mean, in a way, it reminds me of you describing your process while writing Easy Beauty. Fumbling forward in the dark—

CCJ: One thing I try to teach my students—which is probably also something I ripped off of Deb, but then twisted—is: try to make friends with failure.

I: Try to make friends with failure?

CCJ: It’s one of my little maxims. If you’re fundamentally afraid of failure, you aren’t going to move forward in any real way. In my opinion, you have to court failure. Be its best friend, in a way. Develop a psychological relationship with failure. Failure is a necessary—and therefore positive—part of the process.

But it’s one thing to teach it, and it’s a whole other thing to live it—

I: You’ve had so much success as a writer. Two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist and all. So much of your failure in that medium is in the past—

CCJ: Let’s not go that far, but I get what you’re saying. I understand that type of failure—I’m familiar with the ways that failure feels.

I: That’s a better way to put it. You’re already best friends with failure in terms of writing. But with dance, you’re really out of your comfort zone again.

CCJ: Right. It’s a totally new space. A totally new art form. Different people are engaging with the art.

Have you decided on your perfect treat, yet?

I: I think my perfect treat today is going to be ice cream.

CCJ: Great choice. I think I’ll join you.

I: It’s interesting the way all of these things tie together. Devotion as a way of making the tedious parts of life bearable, becoming best friends with failure in order to not shy away from new experiences. Do these ideas also inform your feelings around being a mother?

CCJ: I didn't know I was pregnant until I was five and a half months along. At that point the feeling was, “Well, we’re doing this, I guess.”

So there was—what would be the best way to put this? There was an endless terror around that. I had never even contemplated having a kid before. I’d been told my whole life up until that point that it was extremely unlikely. Then, all of a sudden, there was going to be a child in my life in a matter of months.

Also, in the same way I was saying there weren’t a lot of examples of disabled performers when I was growing up, there also weren’t a lot of cultural models for disabled mothers, either. This changed, I feel, in Wolfgang’s lifetime. In the 12 years that he’s been alive, I’ve seen more and more public models of disability and motherhood.

I: Yourself being one of them.

CCJ: But when I was pregnant—at that time, I hadn’t grown up with any examples to follow. There were no movies in which, say, a disabled woman becomes pregnant and then lives a good life. I couldn't think of any novels that I'd ever read in which that was a major plot line.

Or, if there were examples that were out there, they hadn’t been presented to me yet. I didn't know any other disabled mothers. I certainly didn't see any on the cover of magazines. It wasn’t part of the cultural consciousness. There were so many stories about motherhood, sure, but none of them were about the experience I was having.

The only cultural narrative that did exist around disability and motherhood—and for a large part still does—is that it's a very scary thing for many, many people.

I: How do you mean?

CCJ: Well, it's the basis of the eugenics movement, for one. Here in the United States a large part of the eugenics movement was based on this strong belief that we should be sterilizing women who had any sort of disability—even if they were extremely mild cases of epilepsy, or a suspected lower-than-average intelligence. Disabled women were sterilized against their will, and without their consent.

Culturally—and this is still true for many people—one of the scariest things they can think of is a disabled person having a child.

That was the narrative I was raised under. That was the closest thing I had to a narrative about my body and what was happening—and that narrative was reinforced everywhere when I was pregnant.

I: For example?

CCJ: My doctor said to me. “I think it’s unethical that you’re doing this.” People were obsessively worried about me. Others were really disgusted. Very few people were saying, “This is so great! Congratulations!”

I: “This is amazing! This is so beautiful!”

CCJ: Comments like that weren’t really a part of my pregnancy story. To be honest, they weren’t a big part of my motherhood story, either—not until Wolfgang was older. Which made me, well, it made me angry. I had so much love and support from my own mother and my close friends, but it felt like there was no larger cultural guidance. No societal help.

Which I thought a lot about while writing Easy Beauty. Thinking to myself, “At least I'm putting a story into the world—a true narrative, that you can go get at any bookstore that’s about a disabled woman who has a kid.”

I: Write the book you feel is missing on the bookshelf, in a way.

CCJ: It’s not a fairytale. It isn’t all great, or perfect. But it’s a true motherhood narrative. I feel really proud of that.

I: What is it like watching Wolf perform in Matty’s pieces?

CCJ: For so long I’ve felt, “I know this kid inside and out.” We joke about having the same brain, and having a psychic connection. I know what he’s going to say before he even says it.

I: You can tell which perfect treat he’s going to go for, or special drink.

CCJ: I know what he's gonna want before he says it. We really know each other so well. It's that deep connection you have with your child. He came out of my body. We’re made up of each other’s cells and DNA.

But when I watched him perform? I’m seeing this completely new side of him. It felt like I was meeting him for the first time. There was this utter composure. A maturity that shocked me, and I have a lot of belief in his maturity. But he was so brave and so confident. A truly gifted performer. Like I said, a side of him I had never seen before.

I believe that art really allows you to see someone completely differently. You can find a whole other way of loving a person through what they created.

I: In a way, it sounds like what you were describing earlier, when you discover a new room in the church of your devotion. Finding this whole other nave you didn’t know anything about, but in this case it’s your son.

CCJ: Exactly. Watching this completely new side of him blossom in front of me. I think it's a wonderful part of parenthood—this great gift, to watch your child become their own person.

It was an incredible moment. All I could think was, “Who the fuck is this?”

I: We were saying earlier that being curious can, at times, be hard. Do you find it even harder to stay curious—to have this “yes-ness” orientation toward life—as you get older?

CCJ: No. If anything, I think I’m becoming more curious.

I: Why is that?

CCJ: Because I'm closer to dying.

[Editor’s note: I stop walking for a moment to let out a laugh so loud that a few nearby pigeons take flight.]

I: Jesus. Say more.

CCJ: The closer I am to death, the more desperate I am to learn. I can feel the clock ticking.

I: Can you give me an example?

CCJ: I’ve always wanted to go to Japan. When I was 20, I’d say to myself, “There’s plenty of time. I’ll surely get to Japan someday.” But now? I might not. Not if I don’t plan some things. Not if I don’t make some serious choices. So we’re looking at tickets.

There are so many books that I assumed I'd have time to read—or hell, books I assumed I’d have time to write. I think the pressure of curiosity only increases as you get older. Luckily, I have a child.

I: Wolfgang helps you be more curious?

CCJ: Absolutely. The older he gets, the more curious he gets. I know it’s cliché, but I really do get to see the world anew through his eyes. I get to go to places with him that I’ve been to, but he’s experiencing them for the first time. It’s really inspiring.

Do you find it harder to stay curious as you get older?

I: I agree with everything you’re saying, but for me I think there’s a temptation to grow stagnant. You have to remind yourself to stay curious, I’d say.

CCJ: I’m definitely more selective in the things I’m curious about. My time is more limited, so I really want to focus on the things—and people—that I love.

So I get what you’re saying, in that sense. I find myself asking, “Do I really want to get on the G train at 10pm to go see this band play?” There are things I’ve experienced that I used to be curious about, that I’m less curious about now. I find myself needing to go to fewer parties.

But my general curiosity is still very strong. I have a better understanding that time isn’t infinite. So yes, I’m less compromising. I don’t need to spend time with people I don’t want to spend time with anymore. But I’m doing that because I’m protective of my time. I have a lot of boundaries, because I want to use the time I have left to be curious about the things that really interest me.

I: Death can be one hell of a motivator.

CCJ: You’re right. When you see death up close—which both you and I have—it really can make you conscious of your own limited time.

I was taking care of my mom when she was sick—and I remember telling you this at the time—but all I heard was this loud voice, my future self screaming at me. “Don’t delay your joy. Don’t delay your joy. Don’t delay your joy.”

So I’m making a conscious effort to live with a lot of joy.

I: How do you experience walking in the city? How do you experience yourself “moving through the world at a human pace,” as Garnette Cadogan puts it?

CCJ: With a lot of pain. I mean, doing this is a pain in the ass, to be quite honest. So I’m glad you asked this question

Walking is very romanticized. There are whole schools of thought in philosophy—the peripatetic philosophers, for example, who believed you really couldn't do your best thinking unless you were walking and moving around. Socrates famously walked, and there are all of these great travel writers and poets. There’s this whole incredible history that champions the value of walking, which is all true and fine. But my body? My body fucking hates it.

Right now I’m in pain, and I’m tired. My joints hurt. The amount of walking I’m doing now will exact some sort of cost from me later, and that’s always the case. Which is fine. I wanted to go on this walk with you, much like I wanted to walk this loop with Wolfgang during the pandemic. But if we walked more? If we walked further? If we walked a really long distance? I would pay a very heavy price for that later, physically—and during.

All of this means that I have a different relationship to walking.

When you first asked me to do this, I was thinking about taking you to Times Square. I was picturing us taking a very unpleasant walk. So you could see what it’s like for me all of the time, especially in crowded places, where people will jostle me and push me aside. But even now, here, on this quiet street with a nice breeze, my body is in pain. I'm hot, I'm tired, my back hurts, my hip hurts. Again, it's also quite beautiful and worth doing—but there’s always a price.

I think it's good for you, as someone who's writing walking and moving through the world at a human pace, to think of all the vastness of experiences there are for people.

I: Absolutely.

CCJ: Thinking about that, makes your subject stronger, and more vital.

For me, walking anywhere is like I'm always in Times Square. I’m constantly trying to crowd out the noise of my own body. So I thought you and I walking in Times Square in the middle of summer might be a good metaphor for that.

But then I said, “Fuck it. Let’s get treats.”

Hesitantly, I ask Chloé if my special drink can be a black iced coffee, while promising her I’ll do a better job finding a more intriguing beverage the next time we walk to Treats Crossroads.

“It’s your special drink, Isaac. If your special drink of the day is an iced coffee, that’s great.”

When asked what she plans to do after our walk, Chloé tells me that she’s going to rest on her couch and cuddle with her dog, Dolly. But first I turn off my recorder again and we simply catch up as friends, talking about such important subjects as how big the chunks in a chunky ice cream should be.

“Careful,” Chloé says to me. “Your perfect treat is dripping.”

Looking for another way to support me? Consider picking up a paperback copy of Dirtbag, Massachusetts for yourself or a pal. Thank you!

Love those smiley faces at the end. Huzzah for perfect drinks and special treats. They GET it. 🤸♀️ Loved hearing with frankness about disability and its intersection with joy. And contemplating how devotion transforms tedium into love 👏 💉👌 Thank you both!

Huge fan of Chloe's work and loved reading this chat!