A Walk Through Anand Giridharadas's Teenage Dream of New York City

"You don’t take a helicopter to the top of the mountain. You climb the mountain."

It’s early in the morning and I’m on the Q train during rush hour. Everyone is masked, but it’s still a new sensation to be standing shoulder to shoulder with so many people. Sliding out of the way as commuters enter and exit the train car. Bumping into tourists who refuse to take off their backpacks. Unintentionally brushing hands with strangers as you both reach for the same stanchion.

“Excuse me.”

A woman behind me gestures at a bookmark on the floor. Without even thinking, I reach down and pick it up, handing it back to her. She smiles behind her mask, nods, and goes back to reading her novel. I marvel at the simple thing that I have just done, that I certainly wouldn’t have done a year ago.

By the time I’m at The Strand I’m fifteen minutes late—another new sensation. When was the last time I was late for anything? But Anand Giridharadas is there, standing outside the bookstore, patiently waiting for me. We hug, and then launch into a conversation and meandering walk that will fill up our morning and stretch on into the afternoon.

[Editor’s Note: Today’s Walk It Off is a joint interview. While I was walking and talking with Anand Giridharadas, he was also interviewing me. You can read that conversation over at his Substack, The Ink.]

Anand Giridharadas: As a kid, I was obsessed with New York. I would come up, even if only to spend the day.

Isaac Fitzgerald: Where were you coming up from?

AG: Maryland. Suburban DC. So I would come up to New York—on my own—and just walk around. Soaking it in.

I: On your own?

AG: Yes. But I was the kind of boring teenager, I’m ashamed to say—my parents knew beyond a reasonable doubt that I was not going to drink. I was not going to end up coked out in some loft in SoHo. In a way, the fact that they let me visit the city on my own is a kind of a sad testimony to the type of teenager I was.

So on today’s walk, I want to take you through what I’d call my “imagination oil fields” of New York. Maybe that’s not the best metaphor. “Imagination solar farms?” “Wind turbines?” I’m against oil, is what I’m saying. But you understand what I mean. The places where I dreamed, as a teenager, of one day becoming a New Yorker.

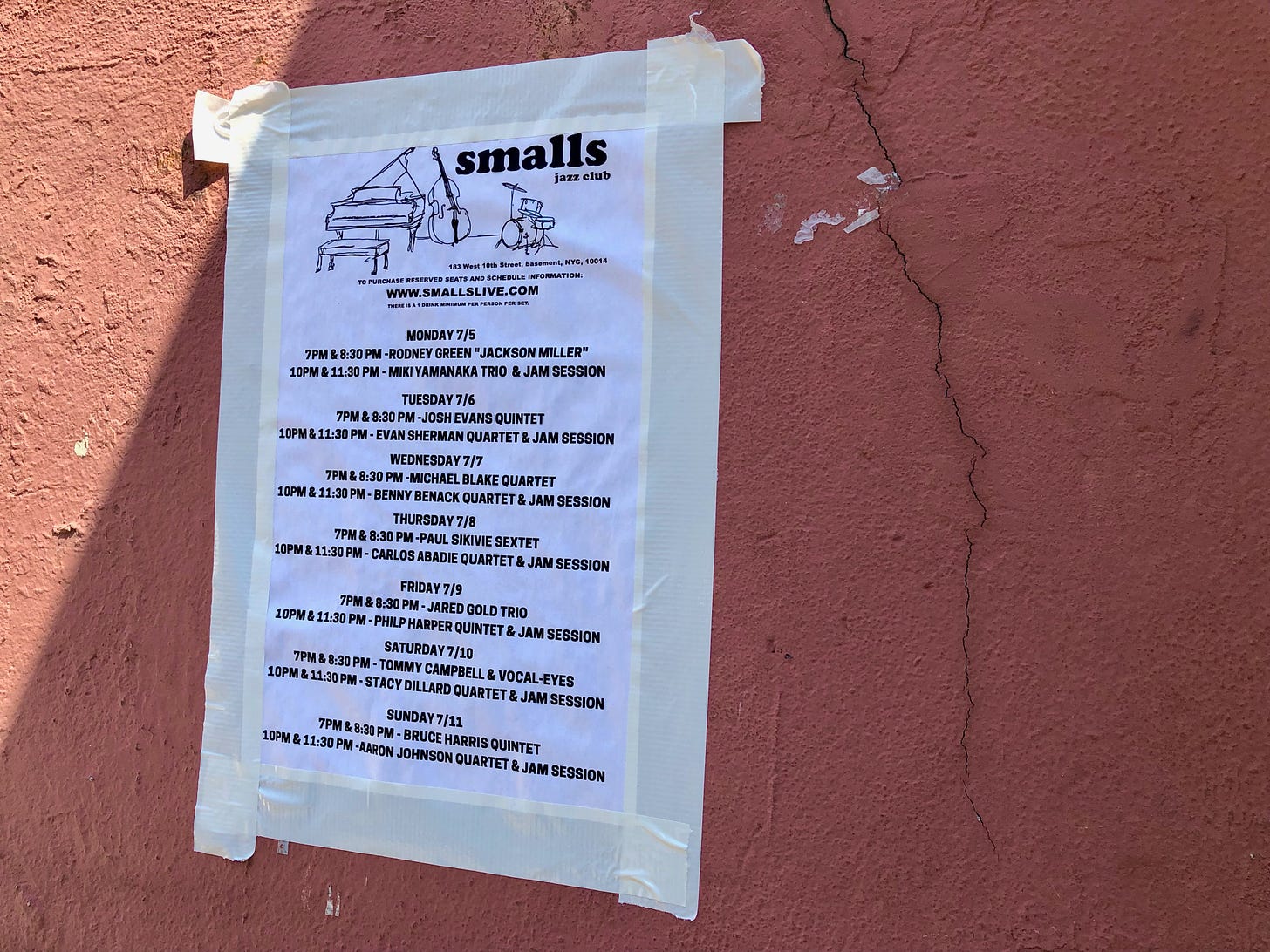

The Strand—where I’d buy one dollar books. Cinema Village—where I’d sit and watch really out there films, the kind they weren’t showing in suburban Maryland. Caffe Reggio—where I’d dream of being a writer. Smalls—a jazz club where you could spend an entire night listening to live music for $20. The places where I would come that made me realize, “This place is different.” That made it clear to me that New York was—for me—the top of the mountain. And you don’t take a helicopter to the top of the mountain. You climb the mountain.

I: Would you say that part of wanting to live in New York City was that you felt at home here?

AG: I’ve always felt—more than comfortable in New York—I feel safe in New York. And I understand that my sense of safety is reversed from a lot of Americans. Not a lot of New Yorkers, but a lot of Americans. A dominant sense of safety for many Americans is isolation, distance from people, homogeneity, land. Whereas maybe my safest space is that subway car I was just on. I really feel like nothing can happen to me if all these people are here. And I mean that in the simple sense of, “There are witnesses here.” But I also mean that more deeply as, “The world is here.”

Now I understand that, for many Americans, that subway car is the nightmare. But for me, it’s safety in numbers. The subway car is the city. If all these people are here, from everywhere, living every kind of life—the refugees of every country, but also the refugees of every state. Every mountain town that’s mean to gay people, every suburb that’s prejudiced against trans kids. We’ve got you all here. That’s why New York feels like the safest place in the world to me.

I: So what was it about places like Caffe Reggio that spoke to you as a teenager?

AG: I had an idea of this life. Living in New York. Being a writer. Writing and thinking and living in the company of 8 million people. It all felt so elusive. But when I was sitting in cafes like this one, where the tables are too small, drinking coffee—

I: Faking it until you make it, in a way.

AG: I once heard a definition of “kitsch” that was, “The effect without the cause.” And until I could figure out how to actually become a writer I just went for some of the effects, because I didn’t have the cause yet.

I: But it actually worked, in a way. You did sit in these places and then—eventually—you do go on to be a writer. To live in New York City. Is it an A to B correlation? No. But there’s something there, right? Something about ambition. About wanting it.

AG: There’s this book about the American psyche, and how there’s this gene, a risk-taking gene, that’s overrepresented in Americans. And I only bring that up because I feel there must be a similar gene—or maybe just a gene in a metaphorical sense—that New Yorkers have, where they can picture that end point. The life they want to live. And it’s not the house and the yard and the fancy grill. It’s this life with all these different people. So many people I know who’ve come here, made it here, and stayed here—there was really this fire, this picture of what it would mean to be a part of this city.

I have family, friends, people I know who absolutely love coming here for vacation. But the city holds zero appeal to them in terms of living here. I wrote a book, The True American. The main character in that book is Bangladeshi. He moves to Queens. Lives in a shared apartment. Tries to get into school. Tries to do this, tries to do that. And his take on New York is, “This is way too much like Bangladesh. I didn’t leave Bangladesh to come to ‘Skyscraper Bangladesh.’” So he’s like, “What is not that? Dallas, Texas.” So he moves to Dallas. It’s a long story, but eventually he gets shot in the face in Dallas. And you might think that after getting shot in the face, blinded in one eye, he might come back to New York. But for the ensuing twenty years he stayed in Dallas.

So I asked him about this, and he said, “New York’s not my conception of freedom. I feel free in Texas. I feel free in Dallas.” This is a Bangladeshi immigrant who was shot in the face by white supremacists and he’s like, “But the parking lots. The space. You don’t have to wear fancy clothes to restaurants. You can wear whatever you want. It’s easy. It’s accessible.” And that was his idea of what it means to be free. And that’s something that fascinates me. It’s what I find so fascinating about these geographies. That we can feel freedom, possibility, and community, in such varying and different ways.

But for me it was this. The idea of New York City. Because it was so connected to the idea of writing. To the idea of art. Just colliding with people and hoping that words and beauty would come out of it.

I: So you loved the bookstores, you loved the cinemas, you loved the cafes. You also loved the jazz clubs. Why were you drawn to them?

AG: Smalls was a place, like I said, where you could pay $20 for a ticket and listen to jazz all night. Sometimes toward the end of the night other musicians—musicians not on the bill—would get up and start playing. So Smalls isn’t, you know, Blue Note, or one of those places that’s the main jazz club to visit when you’re in New York City. But here’s a story. I’m here at Smalls. I believe with my parents and sister. And I came here often at the time, so I wanted to show it to them. And the owner is like, “The line’s too long tonight, you should go to Fat Cat,” which was another jazz place around the corner.

And I said, “No, I don’t want to go to Fat Cat. I want to show my family Smalls.”

But he insisted, “Go to Fat Cat. I own Fat Cat too. This line’s too long. Go to Fat Cat.”

And I kept resisting. So finally the owner says to me, “Jimmy Cobb is playing at Fat Cat tonight. Right now. Go to Fat Cat.”

And I asked, “Who’s Jimmy Cobb?”

He says, “Kid, you know Kind of Blue?”

To which I respond, “The most famous jazz album of all time? Yeah, I know Kind of Blue.”

So the owner goes, “Well, Jimmy Cobb is the drummer on Kind of Blue.”

I guess I had always focussed on the Miles Davis aspect of that album and had not read to the fourth name on the album cover. “Ok,” I say, “I guess we’re going to Fat Cat.”

So we head right around the corner from Smalls and go to Fat Cat. And we see Jimmy Cobb. Playing jazz. And jazz was very important to me growing up, which I got from my parents. My mom in particular. We listened to jazz constantly. We made tapes, and would play them on road trips. So when I listen to Kind of Blue I can actually see landscapes—the countryside from those road trips—in my mind.

But Fat Cat was a big place, there was a bar and pool tables. Not everybody was there to see Jimmy Cobb. Or even listen to the music at all. So again, it’s another one of those moments in New York. There is a room, that is an afterthought room—even in the bar it’s in—it’s not the most notable room. And it’s not even the main venue. It’s the second venue. The spillover place. And actually neither of these places are the fancy place. They aren’t Blue Note. But you can go that many steps down the ladder and it’s Jimmy Cobb. And in that moment I felt the power of New York. The extraordinarily deep bench of this city.

Speaking of which, would you like to eat some extraordinary Sichuan food?

I: I would.

AG: Ok, let’s head uptown to Café China.

I: I want to take a moment to ask you about your writing. Because you do eventually become a writer, and you do move to New York City. The intersection of politics and business is something you write about often. You talk about it on television. What is it about power that interests you?

AG: When I started as a full-time journalist in India for the New York Times—and what is true everywhere is more exaggeratedly true in India, which is there’s a system and most people are screwed by it—but the way someone like me was taught to tell that story in a place like India, was to write about the people at the bottom. That’s how you illustrate the system. And that’s for a lot of reasons. There’s the poverty porn aspect of it—for publications it makes interesting copy. But there’s also the truth that people at the bottom are more open about their lives. They want themselves to be witnessed. So I did that kind of journalism. It wasn’t all that I did, but I did that kind of journalism. Particularly in India where 90% of people are living in various forms of misery.

At some point, though, it began to dawn on me that writing about this system—whether here or in India or anywhere—by describing the bottom, was like writing about architecture by going into a building and interviewing a guy who happens to be standing in the lobby. That guy didn’t design the building, that guy has no idea why the building is the way it is, that guy just found a place to stand in the building. All his choices, all his surroundings, have been determined by someone who isn’t there.

So by interviewing the man in the lobby, we journalists were ignoring the architect. And when people did write about the architects, it was always done in a fawning way. Forbes putting them on a power list or a flattering profile with a nice magazine cover. And I simply became more and more aware that I didn’t need to keep describing the people with no power. I needed to interview the architects. Write about the people at the top. Write about the people who choose for society to be this way, not the people who are just trying to survive the way society is.

I: Your last book is, Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World. Is philanthropy a scam?

AG: I think big philanthropy in general is a massive class scam. It functions as a sort of collective bribe. It’s a way of bribing, in a sense, all of society. The culture at large. Universities at large. Which professor in America isn’t—whether directly or indirectly—underwritten by philanthropy? Which arts institution—here in New York and around the world—isn’t underwritten? That’s a lot of people the wealthy class are buying off.

So you have thousands of people, bribing millions of people, with hundreds of billions of dollars. Ensuring that these people will nibble and critique at the edges, but fundamentally stay quiet about a system that is built around their—billionaires—imagined, permeant right to suffocate human wellbeing for profit. And it is a bribe that works.

I: Thinking about business, power, and politics. What is one of the more interesting—and dare I say optimistic—things to come out of the last year for you?

AG: In the mid-90s Bill Gates published The Road Ahead, and the rhetoric from around 1996 onward was, “The virtual, nonphysical realm is going to replace”—there was this determinism—“is going to take over and eat the world. Software is going to eat the world. It’s going to eat bookstores, it’s going to eat schools—education will be remote and video. It’s going to eat restaurants. And not only will it be adequate. It will be better. The virtual world will be better.” That became the conventional wisdom for many, many years. And the pandemic was such a powerful—and I think disastrous—test of that proposition.

Because all that stuff was there, and it became a lifeline. You could do school on Zoom. You could order food on your phone. But the way in which life—the joy of life—so quickly withered and died on the vine when there’s no physical connection? It showed up that whole thesis. That whole world view. One of the extraordinary truths of our time is how important the physical still is.

Let’s use schools as an example. The predictions of massive classrooms, all video delivery, maybe a few teachers walking around helping but students mainly being on tablets and video. People would have done that before the pandemic. That is where things were headed before the pandemic. I don’t think that’s where things are headed now.

Will tech still be a part of our lives? Of course. But the idea that everything is going to go virtual, and is going to be better? That feels grossly, grossly discredited.

I: Tech is still very much a part of our lives though, as you said. Another topic I wanted to ask you about is social media. I find myself spending less time on it. Yet, it also gives so many people a voice. Can you remind me of the benefits of social media?

AG: Look, we’re people. We’ve been assholes over there and now we’re assholes over here, with more scale and intensity and speed. And, to be honest, I think a lot of us are rethinking how we use social media and how much time we spend on it.

But one of the things that really keeps me there? Witnessing the world talk to itself. We’ve been talking about cafes, right? And subway cars. You can love to be in those crowded spaces, but you don’t know what those people are thinking. You can’t walk around a subway car and ask every person what they’re thinking. Where else do you watch the world talking to itself? I grew up when it was still quite difficult for all different types of people to say what they thought about all different kinds of things. Some of the most powerful voices now don’t have op-ed columns. They aren’t published by powerful media companies. But I’m hearing them now and you’re hearing them now and my parents are hearing them now.

It feels like open mic night at Grand Central every day and I really love that. When you get up to go to the bathroom and I have three minutes here at the table, that’s what I will look at. Not my mentions and not to tweet something, but just to see what the world is going on about right now. Because there are these moments of beauty and merit, which is what they promised us with the internet.

The problem is the human condition persisted with the advent of the internet. What the early champions of the internet—to get back to the rhetoric of the ‘90s and early aughts—promised us was a cessation of the human condition and the birth of some new, post-human condition. Where we were kinder, less hierarchical—some better, more equal version of ourselves. Which wasn’t true.

But I don’t think the internet has made us worse. The internet has created platforms for the amplification and broader dissemination and more rapid, high-intensity processing of what we’re like. As human beings. Which is beautiful, and creative, and interesting, and funny, and hateful, and resentful, and bored, and contemptuous. And we were all those things in the feudal era, and we were all those things during the enlightenment, and we were all those things in the age of the internet. And I think what changes in each era is—what are the technologies for disseminating those things? What are the filters that intercept some of those things?

But who we are? As a people? That is remarkably persistent.

I think that’s part of why I write about structures and institutions. I think there’s too much emphasis on us. On who we are. On character. Trying to get people to be nicer, etc. I think the structures and the institutions are what matter. We’re going to be these human things regardless.

Because I have faith that society can improve. That our structures and institutions can be better. And I do believe more people speaking helps that. And we’re falling flat on our faces right now. But we’re falling flat on our faces because we’re jumping so high. We’re not just having these reckonings to be a pain in the ass to each other. We’re trying to improve things, and we need to remember that there is a real beauty in that endeavor. In that leap.

By now Anand and I have walked from Union Square to Greenwich Village, up through Chelsea and the Garment District, and ended up a few blocks from the Empire State Building. The food at Café China was spectacular, and we’re both chewing on a stick of Wrigley's Big Red that the waiter gave us with our bill. When we started, it was 9am and the sun was low in the sky. Now it’s almost three and the city’s heat bears down on both of us.

Despite New York’s wet warmth we hug goodbye, and I make my way to the subway. The train car is less crowded than it was that morning, but I remain standing. A woman’s water bottle falls to the ground and rolls underneath the seat in front of me. Understanding that I wouldn’t even ride the subway a year ago—let alone get down on my hands and knees—I lower myself to the floor and retrieve the bottle. I hand it to the woman and, still on my knees, look around the train car.

I wonder what everyone is thinking.

[Editor’s Note: Reminder, today’s Walk It Off is a joint interview. While I was walking and talking with Anand Giridharadas, he was also interviewing me. You can read that conversation over at his Substack, The Ink.]

Fantastic! two interviews from two very different writers. (yours has photos too, which makes it even better....)

Love this interview. And the photos?! Isaac, you have a great eye